The Segal method and the UK's self-build movement

In 1962, the German-born architect Walter Segal was living in Highgate, north London, and planning to demolish and rebuild the family home: a major construction project that would take over a year. To accommodate himself, his partner, and six children in the meantime, he created a “little house” in the garden: a wooden frame erected on paving slabs, then insulated and wrapped in a weatherproof shell, with windows that were simply sliding glass panels. The whole thing cost £800 (about £12,000 or $16,000 USD today) and took two weeks to build; all the materials were bought and used in their pre-cut standard sizes, so the house could be dismantled and the material reused or resold. Instead, the structure lasted fifty years. That modest house redirected Segal’s career, making him an evangelist for radical simplicity in architecture and construction — for what ordinary people could do with grit, patience, and a heap of cheap lumber. He saw revolutionary potential in democratizing house building, through the sense of pride, ownership, and community that would rise with every wooden frame — a revolution that continues today.

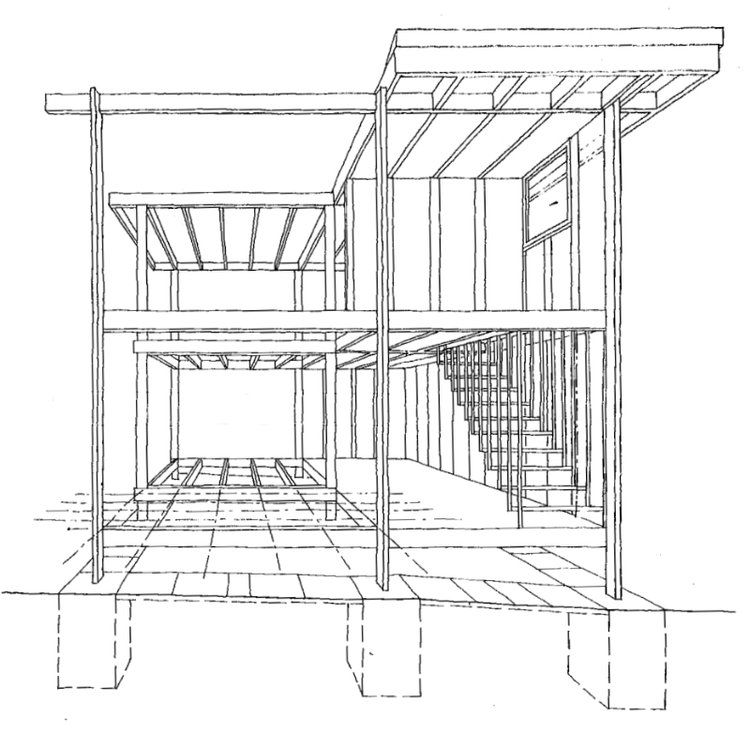

The Segal approach, as it developed from that first little house in the garden, works with what’s readily available, from land to materials. Houses are built on stilts anchored into concrete bases, so there is no need to level the ground to lay a foundation. Wooden frames are bolted together on the ground with hammer and nails, then hoisted into place and braced diagonally until the roof, often finished with grass, can be placed on top. The method uses affordable materials, in off-the-shelf dimensions: usually 2x4 feet, or 600x1200 mm, with 50 mm-wide supporting columns. With this approach, Segal said, “buildings become assemblies, and no longer, in the traditional sense, structures.” The wet trades—bricklaying and plastering—are eliminated from the process. So, too, is the architect. An amateur sketch of the layout can serve as a blueprint. In theory, a single person with the most rudimentary carpentry skills could draw up a plan and execute it mostly by herself, equipped only with a tape measure, saw, hammer, plane, drill, and spade—plus a few friends and a crane to lift the pieces into place.

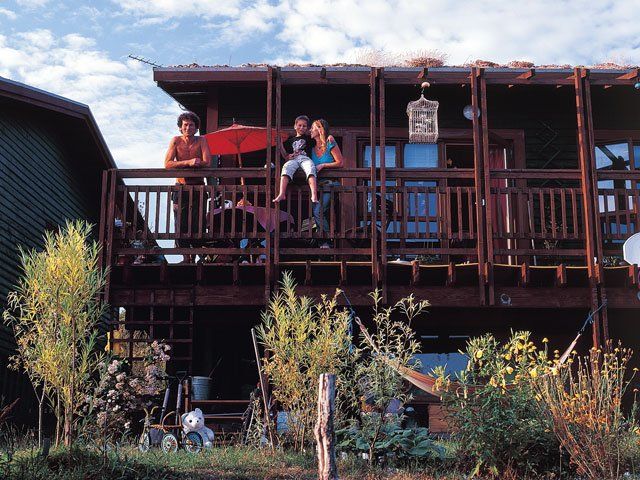

Simplicity, however, does not mean uniformity. Part of the appeal of Segal’s method is its flexibility. It’s been shown to work up to three stories, with roofs that can be flat or pitched, and as none of the interior walls are load bearing, they can be unbolted and moved at will. Segal believed a house should adapt to the needs of its inhabitants, not the other way around. So if an extension needed to be added, a deck bolted on, a wall removed, or windows moved or enlarged, that was a simple task—or at least, far simpler than it would be in a conventionally constructed house.

Although Segal developed his self-build principles somewhat by accident, he was drawing on a wealth of influences, reflecting his unconventional upbringing and training. Born in Berlin in 1907, the son of a prominent Romanian Jewish painter, young Walter moved with his family to Switzerland at the outbreak of World War I, where they lived near a hilltop artists’ colony in the lakeside town of Ascona, near the Italian border. From those “impeccably bohemian” origins, young Walter tumbled into the welter of creativity and chaos that was interwar Europe. He studied architecture in Berlin and turned down an invitation to join the Bauhaus, whose members were family friends, wanting instead to learn how buildings were actually constructed.

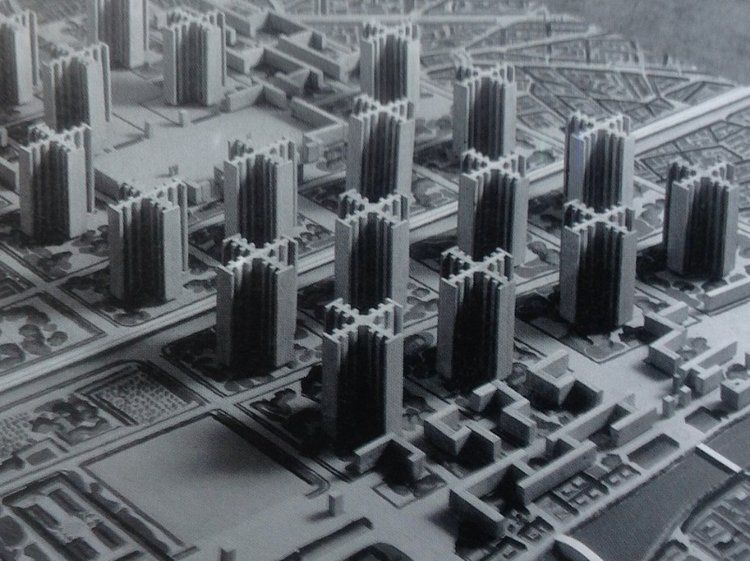

Segal turned his back on the gleeful, futuristic modernism of the 1920s to learn from the past, inspired by modest, makeshift dwellings and the timeless human needs for shelter and community. That put him out of step with leading figures like Le Corbusier, who was busily concocting visions of Paris with its medieval core demolished and replaced by vast high-rise towers, which would house the growing population in rational, minimal apartments. In London, where Segal moved in the mid-1930s, an acute postwar housing shortage saw the government turn its wartime factories over to the creation of temporary houses. These “prefabs,” in a variety of designs and materials, offset the immediate crisis, but the need for affordable housing endured.

During the 1960s and 70s, architects influenced by Le Corbusier built a number of brutalist high-rise tower blocks and housing estates in London, including several that have become iconic, like the Barbican housing and arts complex, and Ernö Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower, in west London. But the hulking concrete structures, heavy and grey against the city’s grey skies, soon became synonymous with urban deprivation and alienation. Segal’s inspirations were as far away from those housing projects as could be, even when he built in their shadow. He looked to early American timber-framed barns, Alpine huts, and medieval half-timbered houses, designs that worked with materials and manpower that were ready to hand, and stripped construction back to its essentials. Over the course of his career, he became convinced of the importance of allowing ordinary people, not just those who could afford to employ an architect, to benefit from the experience of building their own homes.

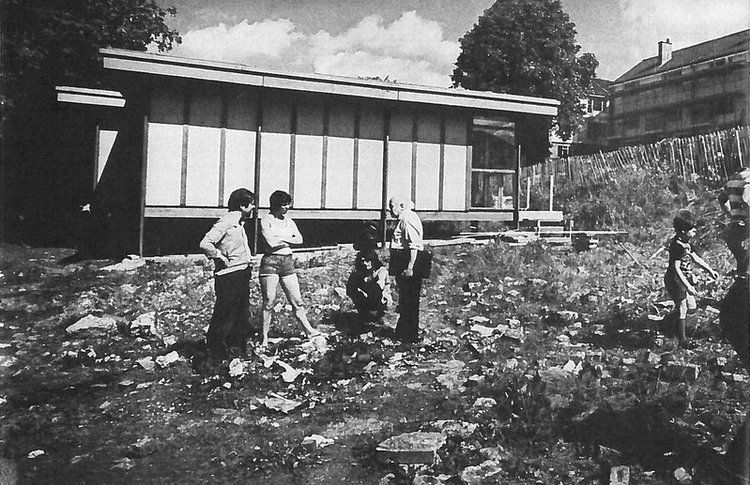

In the mid-1970s, Segal managed to convince Lewisham council, in southeast London, to take a chance on his vision. On a handful of small sites, too steep and tree-covered for standard builds, families waiting for social housing would be given the chance to build for themselves. Segal oversaw the structural calculations but sat down with each family to figure out the plans. According to Jon Broome, a fellow architect who worked with Segal and now carries on his legacy, “he was dead keen on people having input into how they were designed.” He ran a school in the evenings to teach the parents and older children how to handle tools and approach the work. Most people had no building experience whatsoever: one couple, Dave Dayes and Barbara Hicks, had only ever put up shelves when they enlisted in the two-year build. Each family worked on their individual home, then came together with their neighbors when it was time to raise the main frame of a house. Dayes remembered Segal as a philosopher, as much as a practical leader: “When he came, he’d talk for hours, so nothing got done.”

Segal Close (completed in 1982) and Walters Way (finished five years later, after Segal’s death) have become showpieces for the durability, personality, and adaptability of his method. The houses, each facing a different direction, are cohesive but distinctive, characterized by big windows, colorful paint, and idiosyncratic extensions like a yoga studio. Nestled close to trees, they feel far away from London, and are “routinely mistaken for prefabs, an artists’ colony, Swiss chalets, eco-houses, a kibbutz, Scandinavian holiday cabins, Jamaican beach houses—or even a Japanese temple.”

Since construction, the inhabitants have made changes to combat the major drawback of the Segal houses: their draftiness. They’ve installed double or triple-glazed windows and better insulation (although Walter thought residents should just put on another sweater). These changes, and the addition of solar panels, help enhance the energy efficiency of the design. But the houses have inherent advantages, too: Alice Grahame, a Walters Way resident who has written extensively about Segal, points out that these houses are free from the damp, cracks, and subsidence that plague conventional homes on south London’s heavy clay soil.

The development has evolved past its original design in another important way. At the end of the project, the builder-tenants were offered the chance to buy their homes, and all of them did so. Many have stayed, but when owners do decide to move on, their homes are sold on the open market. The current residents understandably want to promote and preserve Segal’s legacy, and their efforts only increase the appeal of these rare and special houses. While the oddness of the construction can scare off mortgage lenders and keep prices somewhat lower, the homes today are far out of reach for the kind of people who originally picked up hammers to build them.

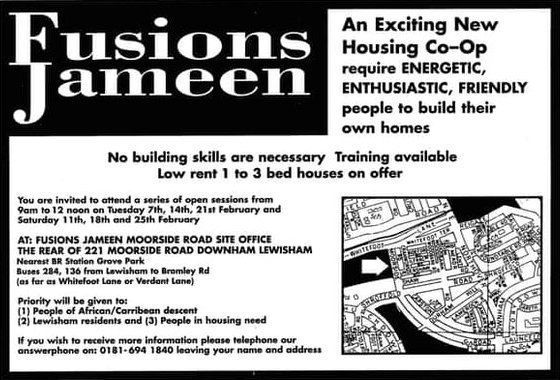

Other Segal-inspired projects, however, hew closer to his belief that community is built, not bought. In the late 1990s, Nubia Way, also in Lewisham, explicitly linked the self-build method to racial justice. Led by London’s first Black housing cooperative, Fusions Jameen, the Nubia Way builders did not own their homes but earned permanent rent discounts for their sweat equity. "People who had bad credit records, people who were in greatest housing need, anybody could build and get excellent housing if you were prepared to give your labour,” recalled one resident, Tim Oshodi. It was no small investment: builders worked between twenty and forty hours per week, more than a thousand hours in total. The Black self-builders faced another challenge unique to their scheme: the surrounding area was an epicenter of far-right, racist activity in the 1990s, so duties included taking turns staying at the site overnight to guard it. Despite their precautions, the site was attacked by arsonists three times.

But they persisted, and eventually, the homes were ready to live in. Years ahead of their time, the homes have low embodied carbon, grass roofs, and recycled insulation. The residents helped regenerate a small, trash-filled strip of land behind the houses into a community park. Nubia Way struck a blow against the deeply ingrained British (and American) notion that renting is an inherently unstable way to live, a conviction that ignores the role of landlords in creating that instability. The allied argument, that renters do not—and should not—truly care about their homes, is boldly refuted by a project like this one, which bakes caring into the very foundations (or foundation-posts) of a house. Ownership is redefined from a bank loan to a hands-on, years-long process of building. Archbishop Desmond Tutu led a congregation in this part of south London in the early 1970s, and his ideas left their mark on the Nubia Way builders. “[He] says there’s a thing called ubuntu, where we are stronger through our community,” explained Oshodi.

In Brighton, on the south coast of England, another Segal-inspired development also made its housing available specifically to low-income and housing-insecure families. The Hedgehog Cooperative is built on the edge of the rolling South Downs hills, on a council-owned site that had been rejected by two commercial developers. A year into the build, in 1999, the group was visited by the television show Grand Designs, which usually showcases the architectural follies of people with more money than sense. This was no escapist property porn: the houses were bare shells, and the builders struggled to manage childcare and survive on part-time jobs that could fit around their commitment to thirty hands-on hours per week. When the structure of one house was hauled into place with the help of a rented crane, children on-site and viewers at home watched in awe, and the presenter likened it to an Amish barn-raising.

Twelve years later, Grand Designs returned to the Hedgehog site, to see a row of colorfully painted houses on the hillside, camouflaged by grass and wildflower roofs. There was a community orchard and gardens, and a gaggle of teenagers and young adults, who had grown up in this rarest of communities, gathered around a fire pit. A vanishingly tiny number of children anywhere can say that their mother built their house, and one of the most striking aspects of films of Segal self-build schemes is the sight of women wielding hammers and hauling up walls along with men. All of the ten original families were still there, renting, with no plans to leave. Their cheap housing costs had freed them to return to their education, and to pursue careers not guided by money: they became carpenters, care workers, and teachers. At the end of it all, the presenter asks, “Why aren’t we building more of these?”

The more you read of the utopian possibilities of these self-builds, the more insistent that question becomes. Scale, inevitably, is the major challenge. There are around two hundred Segal developments in the UK social housing sector, barely a drop in the ocean of demand. There are worries about the longevity and durability of the houses, while new ecological standards, especially around insulation, make the buildings more complicated and expensive to build up to code. Health and safety regulators, meanwhile, are warier today of total amateurs banging nails into wooden posts and hauling them up on ropes, protected by little more than a hard hat and a belief in the power of community.

Political will, too, is lacking—perhaps because these schemes, which are both socially idealistic and highly individualistic, don’t cleanly align with the policies of right or left. Disciples in Britain lament that local authorities in countries like Sweden, the Netherlands, and Germany are far more receptive to self-building and community developments than in the UK, where powerful developers hold sway. Nevertheless, in September 2021, a community land trust called the Rural Urban Synthesis Society (RUSS) broke ground on the largest community self-build yet undertaken in London. With 36 homes in the development, and no developer profit in mind, the scheme aims to keep the homes permanently affordable via clauses to restrict resale prices, and it includes six rented homes for people on the social housing waitlist. The project is overseen by professionals, but future residents had input into the plans and will be involved in the building, alongside volunteers and young people apprenticing in the building trades. Due to be completed within two years, the project will include a community hub (already completed), as well as gardens, a public playground, shared laundry, and spaces to grow food. The head of the project is Kareem Dayes, who grew up on Walters Way.

Kareem’s father Dave Dayes calls Segal “an empowerer.” Against the expectation that only certain kinds of people are able to build houses, he offered another, simpler, and more radical approach. “He said, look, anybody can build a house. All you need to do is cut a straight line and drill a straight hole.” Segal understood something profound about the relationship between homes and their human inhabitants that his contemporary modernists often missed: that people do not fit easily into boxes, no matter how rationally they have been designed. Nor do they stick to the designated paths. Strong communities are those that allow for deviation, for evolution, for collaboration; where there is space and will to respond to changing needs — by digging a vegetable patch or a fire pit, or building a meeting hall, a nursery, or a playground. Segal’s vision was unusually literal and hands-on, but it acknowledged the vital, non-monetary connection between what people put into their homes and communities and what they get out. A building is both an object and a process, and, in turn, it builds so much more, personally and socially: “I’ve built my own house, what can’t I do?”

Further reading on the Segal Method:

- Celebrating Segal

- Walter Segal, Self-Built Architect, by Alice Grahame and John McKean, photos by Taran Wilkhu

- Learning From The Self-Builders, a 1983 talk by Walter Segal

- Nubia Way in the Guardian

- Hedgehog self-builders on Grand Designs