Revisiting Vaclav Smil's Made in the USA

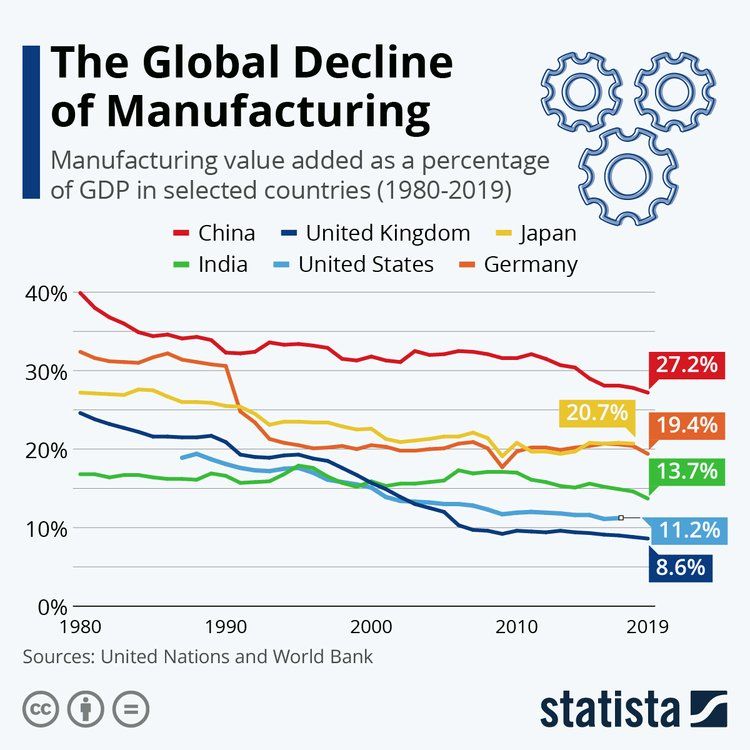

Following the 2008 financial crisis, manufacturing output in the United States dropped by 20% and the workforce contracted by 15%. While many politicians and economists sounded the alarm, others believed there was no need to worry, theorizing that deindustrialization is the logical next step as an economy modernizes (and that there is no economic difference between serving chips and making microchips). Vaclav Smil’s Made in the USA: The Rise and Retreat of American Manufacturing (2013) is a response to those detractors, making an impassioned argument that manufacturing does matter and “that without the preservation and reinvigoration of manufacturing, the United States has little chance to extricate itself from its current economic problems, meet the challenges posed by other large and globally more competitive nations, and remain a dynamic and innovative society for generations to come.”

For evidence of this importance, Smil first takes stock of the manufactured goods that define modern life: Everything from access to food and shelter, to health care and transportation “rests on an assured supply of a myriad of manufactured products.” Even if we were to disregard consumer products, continuous inputs of goods to maintain and upgrade infrastructure are critical to a functioning society. And while manufacturing builds out the base of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the sector’s true value to an economy comes from its multiplier effects. Smil explains that every sales dollar of manufactured products generates $1.40 of additional activity, compared to $1 for transportation, and less than 60 cents for retail and professional services. Or, as Neil Padukone, Executive Director of NYC’s Manufacturing and Industrial Innovation Council, explains, “each job in manufacturing generates at least 5-7 other jobs, including those in other sectors; that number is just 0.25 for retail.” Throughout Made in the USA, Smil argues that the belief a service-based economy can flourish the same way a manufacturing-heavy economy had in decades past is dangerously misinformed.

Revisiting this work nearly a decade after publication is interesting. Even the products that Smil identified as competitive US exports in 2013 (aerospace manufacturing and silicon production) have taken big hits in recent years. Throughout, Smil focuses on the ever-growing deficit with China as a key driver of the decline in domestic manufacturing. The intervening years have seen tumultuous trade policy trends with tariffs imposed on thousands of products in hopes of lowering the deficit. These tariffs successfully reduced the bilateral trade deficit with China, but the deficit grew overall as imports from other nations spiked. The Tax Foundation’s analysis of the tariff strategy found it was equivalent to $80 billion worth of new taxes on Americans and could cost the economy 173,000 full-time equivalent jobs if kept in place. Today, there is much debate around whether or not lowering the trade deficit should be a core economic strategy in the US, but the fact remains that manufacturing’s share of GDP has declined since the 1970s, and supporting and growing the sector is an important piece of economic prosperity.

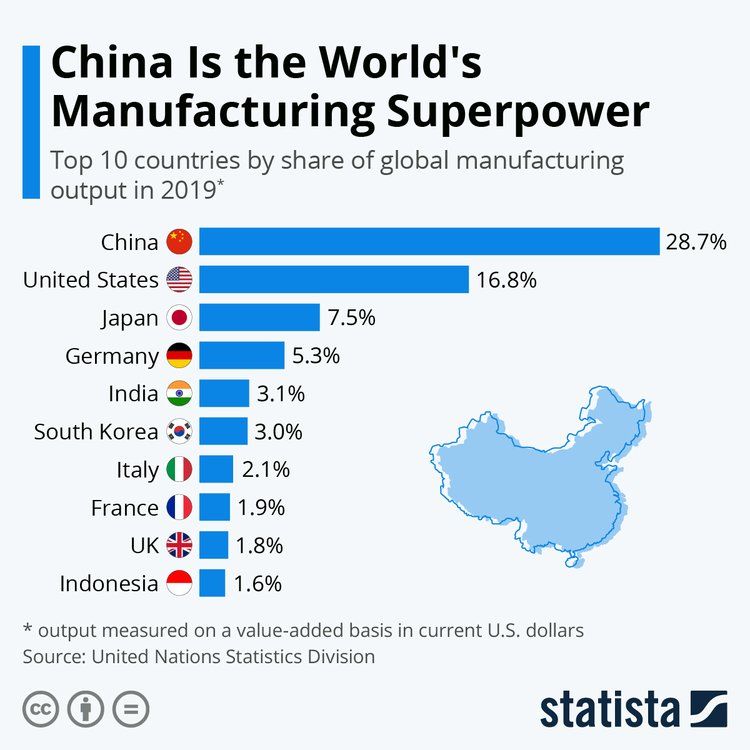

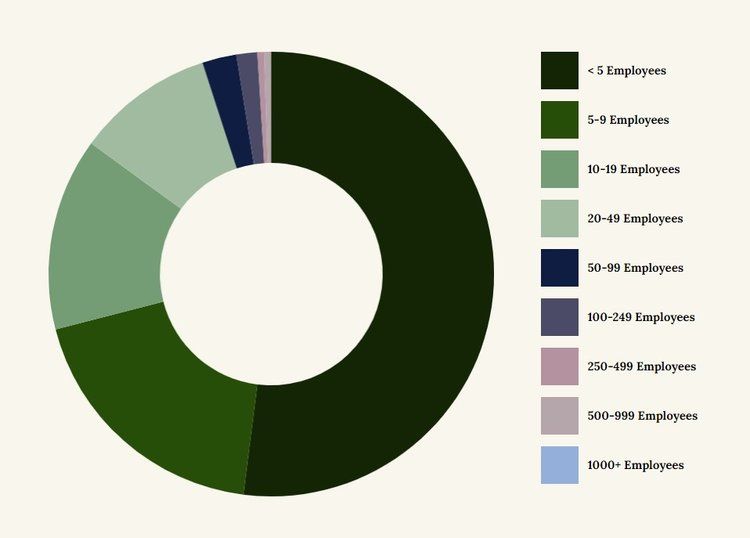

The good news is that despite this decline, US manufacturing is still massive. Coming in behind only China in output, the United States manufactures about $1.8 trillion in goods annually, accounting for 18% of global output. Fostering the ecosystems, businesses, and communities that make up the domestic manufacturing sector doesn’t mean starting from scratch; it means paying attention to what is in place and bolstering local needs. For policymakers, this can be a challenge - EssentialNYC points to “the 'behind the curtain' nature of these businesses [that leaves] them vulnerable to policies that undermine the infrastructure, operations, and future of this vital segment of our economy.” For example, megaprojects like the ill-fated Foxconn Wisconsin project get much of the public attention around manufacturing policy, which leaves behind the small businesses which make up over 98% of US manufacturers. In NYC, there are still 5,000 manufacturing businesses that employ 52,000 people; over half of these businesses have fewer than 5 employees. Supporting the manufacturing sector means finding solutions that work for companies at this scale.

One strategy for supporting these businesses is turning away from innovative products and investing in the production of everyday commodities. Smil remarks that “there is no categorical difference between making ‘just a commodity’ and creating a new high-tech future,” and as such, “abandoning commodity manufacturing can lock you out of emerging industries.” Manufacturing ecosystems that produce the basic goods of everyday life provide the foundation for the next big invention – while keeping us all clothed in the meantime. Supporting these “industrial commons” ensures basic resiliency that can be drawn on when needed. Neil Padukone points to how the existing capacity in NYC was leveraged in crisis: “If we didn't have local garment, technology, and beverage manufacturers who could pivot their operations to provide PPE, hospital isolation gowns, sanitizer, and even hospital ventilators, the city's covid-19 response would've been that much more challenging.”

Another example is the food production industry in California, which is one of the largest local manufacturing center sectors because of the high agricultural output in the state. Martine Neider from SFMade explains that California is a really good place to start a new food product “because it's near the raw goods and it's near the market.” She says this ecosystem is what enables the emerging, innovative food companies who make “the food that's really a biomaterial.” Companies making food from plant-derived molecules are able to prototype their processes in the Bay Area before scaling production in facilities collocated with raw materials in other parts of the country.

She also points to the aerospace industry as an enabler of emerging manufacturing. Over the years, it’s created an ecosystem of people who can do very high tolerance work, and procure materials that are hard to source - capacities that would be out of reach for a standard machine shop. She explains that “it was because we had this aerospace cluster, because of NASA and because of Lockheed, that other businesses like Kittyhawk and Joby could come up and start doing new and innovative work around flight. It's the same ecosystem that the satellite folks can attach to, and frankly, it's a lot of the same ecosystem that Tesla was able to attach it to.”

Supporting and fostering the microbusinesses that make up the manufacturing base enables innovation all the way up the chain, and failing to identify and strengthen the links between them opens up vulnerabilities. Martine mentioned an anodizer that just closed shop - “everybody's really upset. He was in South San Francisco, he was the best, he was the cheapest, and his kids didn't want the business. So it's gone now... That's it.” She believes cities need to work together to identify and support businesses at this scale, and through her work with the Bay Area Urban Manufacturing Initiative, she’s trying to get stakeholders to understand “that if we lose something in one city, that means we're not going to be able to support manufacturing in the other cities - these clusters are really interlinked.”

One emerging strategy for supporting these critical small businesses is succession planning - finding those retiring anodizers whose kids aren’t interested in taking over and aiding in a transition. Katy Stanton, Programming and Operations Director for the Urban Manufacturing Alliance (UMA), outlined how “an estimated 125,000 manufacturing firms are owned by baby-boomers, and risk closure when these owners retire.” She sees this not only as a loss of good jobs, and a threat to local economies, but a risk to national security. The pandemic and ensuing supply chain challenges have exposed how critical local manufacturing capacity truly is.

UMA helps small manufacturers develop succession strategies, with a focus on racial equity and community wealth building. On the open market, these companies might get bought up by private equity firms, or larger corporations, so UMA works to “transfer ownership of manufacturing firms from retiring white owners to people of color, particularly those who work within the business or within the supply chain.” This helps keep jobs local and build wealth in communities that have been systematically kept out of building equity. They’re working to partner with credit unions and smaller community-based lenders to bring in buyers from the factory floor, supporting ongoing manufacturing and building communities.

While so much has changed since Made in the USA was published in 2013, Smil’s insights into the importance of manufacturing have enduring value. He says, “making things remains a quintessential human endeavor without which there can be no prosperous large economies and no socially stable populous societies.” Investing in manufacturing is investing in a stable future, replete with all of the material things that keep us living. We do ourselves a disservice by assuming bleeding-edge innovations are the only thing worth investing in. From basic commodities to emerging technologies, making more things makes our communities stronger.

Thanks to all of the Members who followed along with Made in the USA in Scope of Work’s reading group. We’re now reading The Fabric of Civilization by Virginia Postrel - join us! Thanks also to Kinda, Neil, Martine, and Katy for sharing their expertise.