I’ve been in Sicily for the past week, where the earth is parched and the air is so thick it shields our eyes as we look straight at the molten coin of the setting sun. Looking at the phlegmy haze that hangs around Mt. Etna, I wonder how much of it is topsoil.

It’s impossible not to think about water as we walk around. When we were here in 2018, Sicily was a desert in riotous bloom, a watercolor in green. Everything grows here, fans of banana, lizard tangles of agave sprawling heavily across the dirt, chestnuts, lindens, citrus groves varnished jade, and monumental olive trees whiling away the centuries. This year every leaf is a soil hygrometer, telling its own story of the drought.

Water isn’t fungible here. There’s municipal plumbing, of course, and it delivers ostensibly potable water, but you wouldn’t know it from the way our hosts warn us to steer clear. In the village of Milo, on the eastern slope of Mount Etna, we’re told the water comes from an artesian spring, and it proves to be delicious. Still, when I ask for tap water in the local osteria, the waiter reacts like I’ve asked for a glass of hemlock.

In Trapani, on the western point, the water might be potable or it might not – the municipal water treatment plant is so old the EU no longer considers it effective. It’s still used for food processing, and Trapani is one of the main fishing ports on an island that lives on fish.

Elsewhere, the problem is the pipes: No one seems concerned about lead, but everyone agrees that the water’s disgusting. We use it to wash peaches grown in Bronte, apricots from Mazara, figs sold in Catania from the back of someone’s car. When we actually try the water, it’s as bad as promised, a flavor wheel of off-tastes – metallic, powdery, ineffably stale.

So instead we drink, like everyone else, from a collection of 2-liter mineral water bottles, a gallery of baroque forms. It’s an education in just how varied water can be, dizzying gradients of carbonation and mineral content.

Sicily almost reverses the usual truth, that water is fungible and food is not. Every bar-pasticceria (the all-day diners of Italy) has the same menu of arancini, gelati, granite, pastry, a few sandwiches, a few cartocci. If this really were the Sicilian diet, you could feed the island from Communist-style canteens – or at least the tourists, who at this time of year outnumber the Sicilians. I’d bet much of the food actually does come from boxes rather than kitchens, made in large commissaries, or factories, and dispatched to its final destinations.

So here drinking water, like food, is delivered above ground, thirst made visible. Cargo Vespas and tiny trucks (smaller than an American compact car) unload cases and cases of mineral water in the tourist trap restaurants that line the capillary streets, erythrocytes shedding oxygen.

And the public fountains remain, everywhere. They are reminders of Rome – reminders that you can, and perhaps have to, build empires on water. We see public faucets in every city, people filling jugs by the highway outside Mazara, faucets in the village square, in the fish market in Catania. An honor guard of them guides you down the Valley of the Temples, small monuments to the history of infrastructure and everything that came after. People come for their day’s water, their week’s supply. Fishmongers draw buckets to sluice their tables.

Spigot/ashtray overlooking the Catania fish market. Despite appearances, that nut actually works as a faucet handle. Next to it is the umarell gallery.

To someone living in the US, this seems slightly obscene. Taps in the US, after all, are mostly private property. Public drinking fountains and bottle fillers are amenities for privileged communities, dispensing water by the trickle in playgrounds, museums, and opera houses. In Sicily the public spigots gush with enough force to irrigate an orchard. Drinking water, value added, there for the taking, for free. The definition of public provision. My American eye is drawn to the pool at the foot of each fountain, the inevitable waste.

But the island is deep in a historic drought, and rainfall has been declining since 2003. The water shortage is exacerbated by pipes as rutted and broken as the roads, watering the bedrock like soaker hoses. In Agrigento, meters upslope from the Valley of the Temples, hotels turned guests away because their cisterns were running too low. The grapevines I saw on Etna were lush, but most other farms in Sicily are in crisis.

And down in Siracusa, our host has sprinklers running on her lawn. The house next door has a leaking sprinkler which has been on for days, dribbling into the retaining wall at a gallon a minute. I grew up in Singapore, where the government conducted water rationing drills every few months, in case Malaysia ever shut off the water supply. My childhood was wallpapered with water conservation posters, which admonished us to turn off the shower while we soaped, and told us that we saved a half-liter of water each time we used a tumbler to brush our teeth.

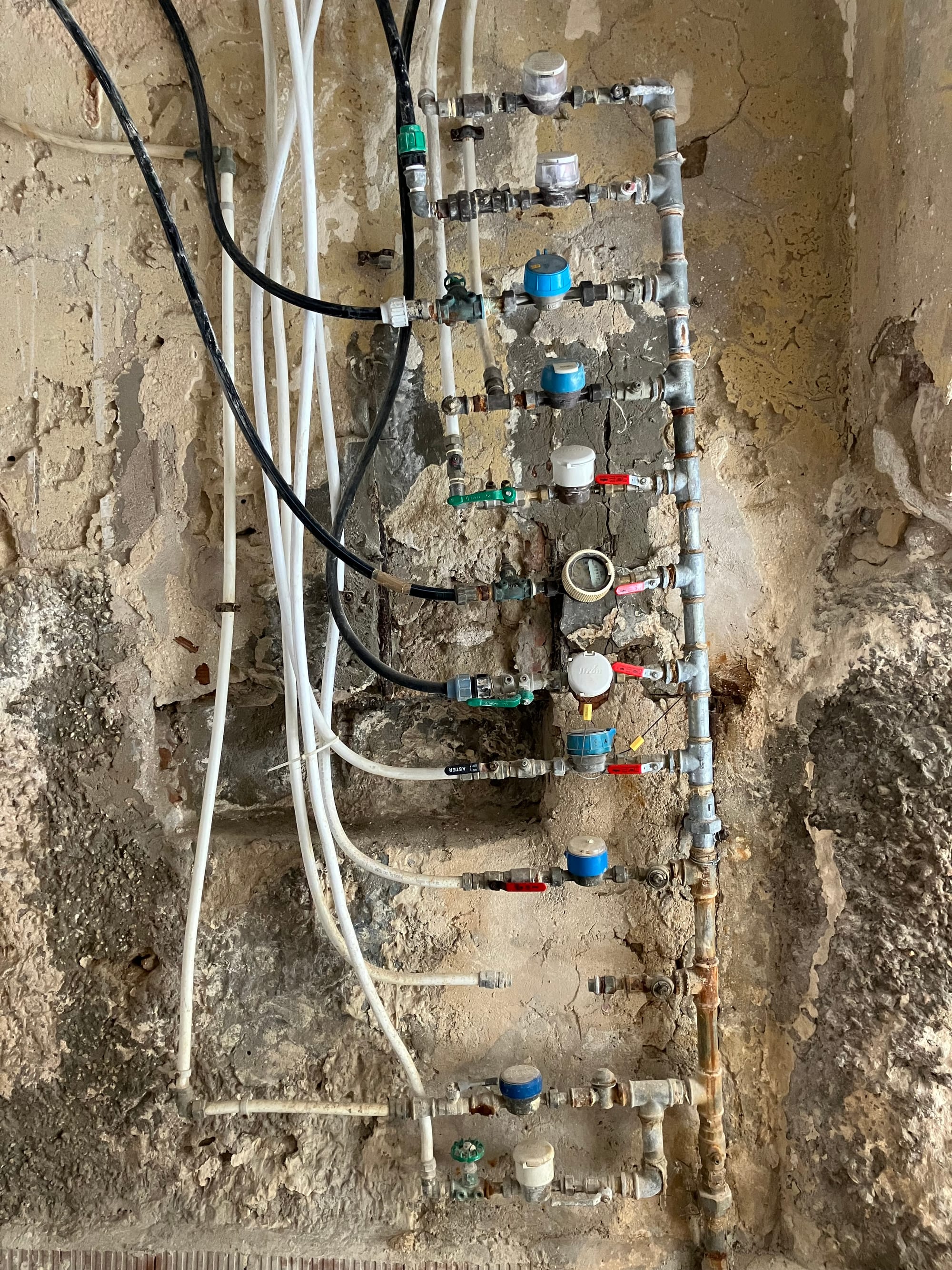

Maybe the built environment, when old enough, is just a particularly picturesque form of technical debt – the sandstone houses with their foot-thick walls, the marble plazas buffed slick by the centuries, the fountains that first brought water to the cities. We feel Hiltis rattling everywhere we go, telling us how violent even minor renovation needs to be. Often the solution is something like this rickety manifold, clinging to a vestibule in Siracusa.

But the tech debt is part of the attraction. I might not be here if the piazzas were striped in concrete and tarmac, even if the water pipes were new and the water tasted better. I’m clearly part of the problem, even if I’m also a source of revenue: one more reason to put off major infrastructural work, one more drain on the reservoirs. Even if you could work masonry like drywall, preservation and restoration come with a price tag, and Sicily can barely afford to keep running.

I found out, after leaving, that there are aqueducts in Sicily. Drinking water was once before delivered above ground. One of the attractions in Palermo, a mosh pit masquerading as a city, is the Qanats, tunnels that brought the city its water a thousand years ago. Water infrastructure used to be built in stone.

This, more than any doric column, makes this moment feel transient and precarious. Each network reflects an entire world – monumental aqueducts erected by tyrants and slaves, built from the same sandstone as the cities they supplied. Public fountains brought water into public squares, commemorating progress while acknowledging its limits, asking humans for the last mile. And now piping corrodes as politicians argue, and this says something about the moment too.

If infrastructure is the result of societies being coherent and coordinated enough to undertake collective projects with collective benefits, perhaps what I’m seeing now is the opposite. A post-provisional state, complex and inchoate.

SCOPE CREEP.

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now