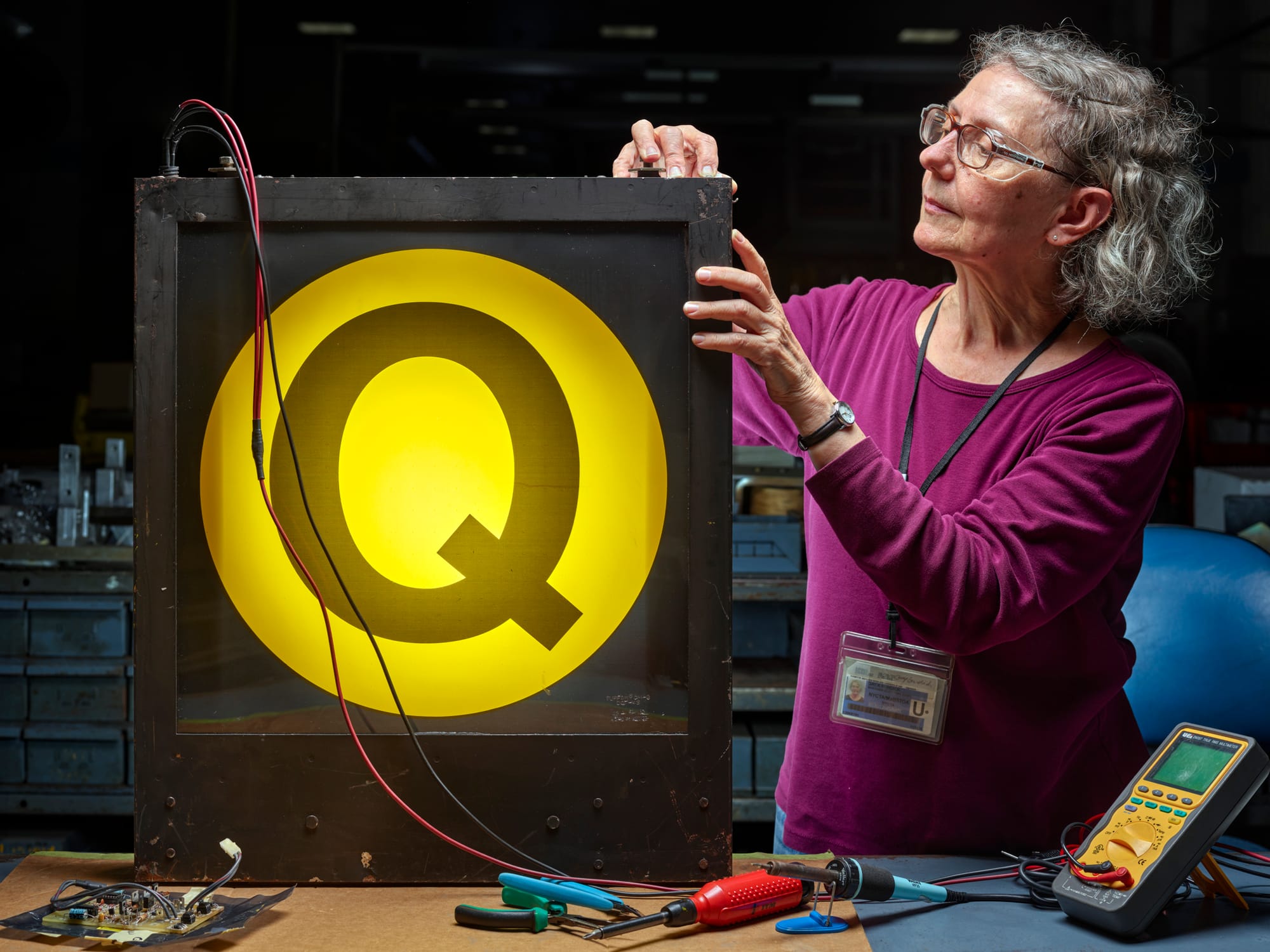

Christopher Payne is watching Gay Burdick work, and I am watching Christopher Payne work.

We’re at the MTA’s 207th Street repair shop, which Payne has, for some time, been photographing for the New York Times. Payne says he wants to wrap up the shoot and publish the photos; the MTA has experienced some turnover since the project began; they want to meet with Payne (and writer David Waldstein) and get a better understanding of what his goals are. While we’re here, Payne wants to see Gay’s workstation again. I’m not totally sure what Payne sees in Gay’s workstation — he keeps talking about her look — but this is what I see:

I became aware of Payne through his previous work in the Times, where he has published shoots from factories that make colored pencils, container ships, and the paper version of the Times itself. His photography is striking, and from the accounts in his most recent book, Made in America, his process is meticulous. Payne will apparently return to the same factory dozens of times, waiting for the moment when a production run lines up just right, or the material being processed is just the right color, or — I don’t know — his subject finally lifts their hand in a particularly elegant way. Payne is an artist, and his art documents, explains, and valorizes manufacturing, fabrication, and maintenance work.

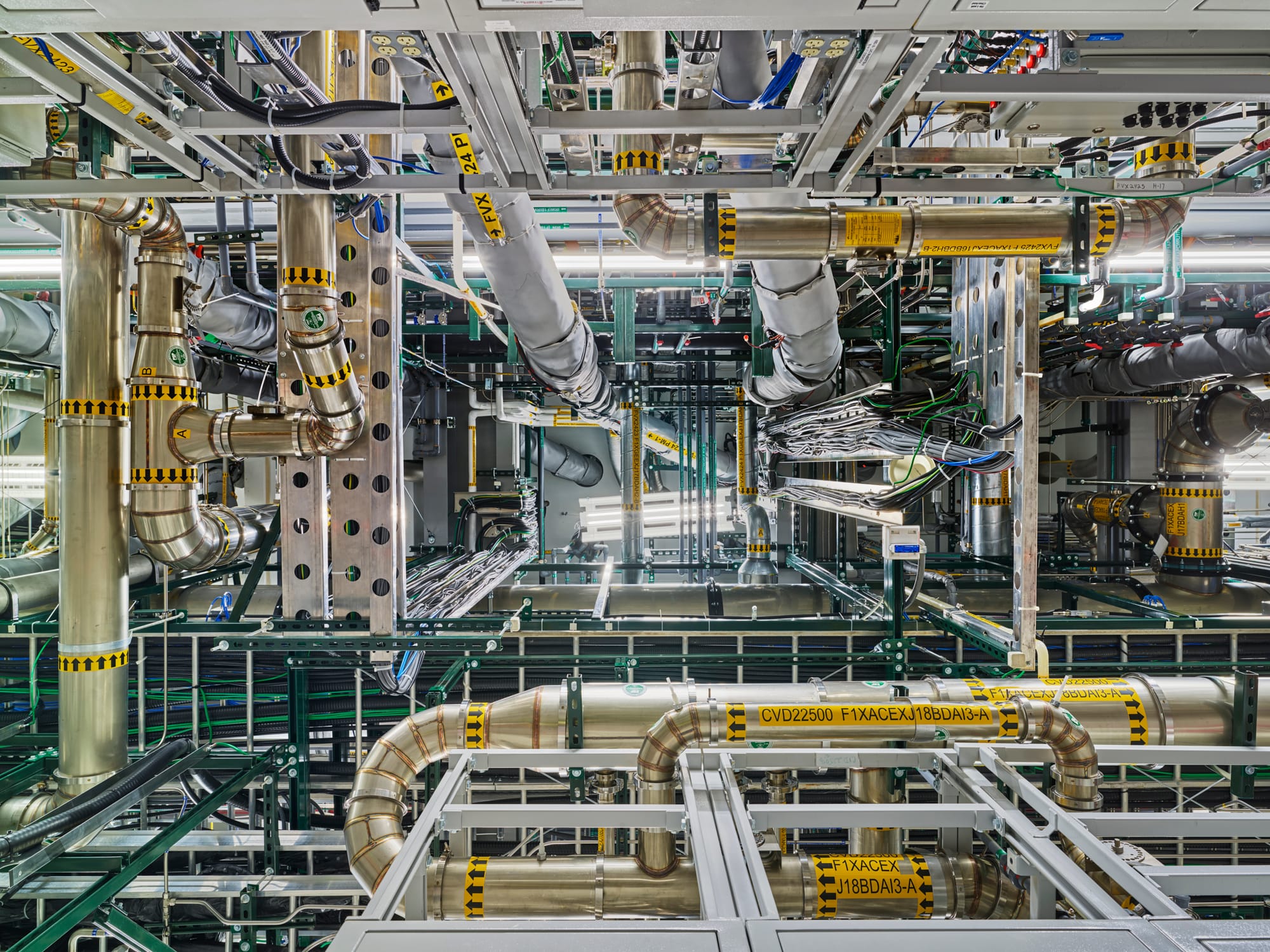

Aspects of Payne’s work might be categorized as genre art. He captures moments in everyday time; he captures human intention and effort; he captures the infrastructure required to make stuff. His subjects are often highly engineered (he has photographed ASML’s EUV machines, Boeing’s 787 assembly line, and NASA’s Space Launch System), but just as often they’re highly soulful (Payne published a book about Steinway pianos; he has also photographed Martin’s guitar factory and Zildjian’s cymbal production process). Regardless of what he’s shooting, Payne’s photographs often feel just as carefully assembled as the objects in them. One of the more notable aspects of Payne’s photography is the way he seems to lift a subject out of its surroundings. Seen through Payne’s eyes, a motor being built is only surrounded by a factory part of the time; other times, it exists in a field of pure black.

There is utility in this framing. When working on complex things, it can be helpful to black-box everything around them, focusing only on their inputs and outputs and ignoring the chaos they might eventually be dumped into. If I were employed to design a motor, I would be careful not to think too much about how its wiring is extruded, or how the power that will eventually run through it is generated, or for that matter what the most efficient method of shaving a yak might be. I would imagine my motor lit by a spotlight, not a floodlight.

But there are also moments when Payne zooms out, and as the reader turns a page in Made in America they see not an isolated process but an entire industrial symphony, sprawling and expansive and in seemingly perpetual motion. There are, of course, engineers who work at this scale too: system architects who coordinate and conduct the various mechanics and mechanisms which make up a factory. Here, the subject of Payne’s photography seems to be modern industrial complexity itself.

I first met Payne on a sunny January day in Gowanus, Brooklyn — a neighborhood whose namesake canal, abused by local tanneries, mills, and chemical plants for decades, is now one of the most polluted waterways in the country. No longer suitable for heavy industry, Gowanus remains a relatively hospitable neighborhood for taxi depots, lumber companies, and a cement supplier. But when I visit Gowanus it’s usually on a trip to my climbing gym, which is around the corner from another climbing gym; Gowanus is also home to a gymnastics camp, an indoor archery range, and the most suburban-looking Whole Foods in Brooklyn. It is a neighborhood beset by competing forces: a haven for light industrial business fleeing gentrification elsewhere, but also the site of lots of gentrification.

Payne and I met at Griffin Editions, a print shop that Payne described enthusiastically as “the place.” He was there to inspect a print of his that had sold, and I milled nervously around, trying to understand what part of the art world I was standing in, and how it connected to the industrial neighborhood around it. A refrigerator in the entry was stocked with more film canisters than I had seen in decades, and the raw but neatly-constructed plywood shelving behind me was stacked with monographs by artists who I assumed had longstanding relationships with Griffin. Payne was inspecting prints of his photographs. One was from a series from Titleist’s golf ball assembly line, and Payne pointed at one of the balls, presumably suggesting how the photograph might be exposed differently on a reprint. I got the impression that he had a longstanding relationship with Griffin, and that it was a collaborative one — a sense that may have been reinforced by the swirls of activity happening around him. In front of me was a large, well-lit table, and behind the table were Payne’s prints, mounted on the far wall. Payne appeared to be discussing them with a manager of some kind, and as he approved one print, another worker slipped it off of the wall, transferred it to the table, and methodically wrapped it into a flat package, taping it up with precision and marking it neatly with a Sharpie.

Payne was ebullient; I imagined that he was excited to have a physical product to show for his workday. He slipped the envelope under his arm and suggested we relocate to a pizza place nearby, and as we walked, I re-explained who I was and started my voice recorder. I went on to worry about the recorder for basically our entire conversation: Payne was the most soft-spoken patron in the pizza place, which was small and full of hard surfaces for competing conversations to reverberate off of. The recording, in the end, was fine.

I, like Payne, have been to my share of factories, and independent of my conversations with him I consider that a point of pride. It is a part of my personal history which feels both distinguished and down-to-earth. But I no longer maintain an active list of factories to visit, and in this respect Payne has me beaten. His enthusiasm for manufacturing facilities is fully inhabited; while I sometimes look upon my own industrial tourism as a distraction, he is clearly energized by the idea. When I described his earlier books as “photography projects,” and suggested that Made in America seemed like something that he might pursue further, he pulled out his phone and swiped through a wishlist of factories that was multiple pages long. A week after our first meeting, Payne emailed me from Ohio; he was shooting a football factory. He was already planning his next factory visit.

As Payne tells it, it was the urgency of his first MTA project that led to his career as an industrial photographer. At the time he was working at an architecture firm: “That was, like, my path,” he said, looking intensely ahead and miming a narrow, straight road. He enjoyed architecture’s collaborative aspects, but he didn’t enjoy “helping someone else fulfill their dreams,” and when he made friends with a superintendent of the MTA’s power department, Payne began obsessively visiting the subway’s soon-to-be-decommissioned electrical substations. “Initially, I was simply thrilled to discover something forgotten and hidden from public view,” Payne wrote in New York's Forgotten Substations. “But as I spent more and more time in them and saw them being destroyed, one by one, I began to feel a poignant sense of loss, and, in turn, a personal obligation to document this vanishing typology.” His MTA contact gave him access to a substation in Chelsea, and Payne started making sketches of the equipment there. Eventually he began taking photographs, rushing to capture these “ruins and relics of a bygone era.”

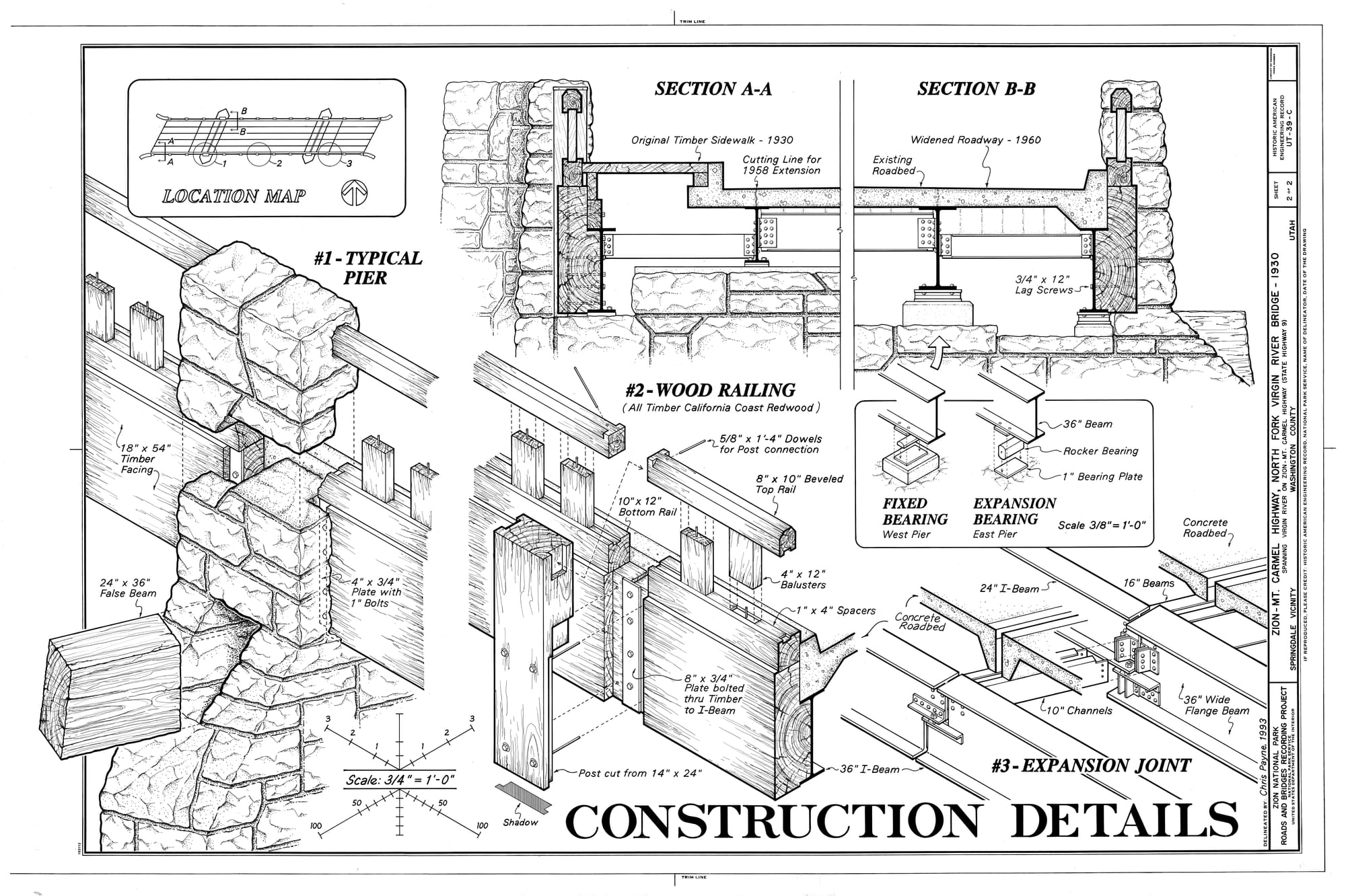

This was not his first time documenting old, highly engineered infrastructure. Between college and graduate school Payne had worked for the National Park Service’s Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), where he made meticulous as-built drawings of the bridges in Zion National Park. HAER (and the other programs within the Heritage Documentation Program) has produced over forty-five thousand surveys since its founding during the Great Depression; when Payne realized that he could be “getting paid to crawl around an abandoned building,” he jumped at the idea. “It was so much fun,” he told me, and the skills he developed there led directly to New York's Forgotten Substations and his second book, Asylum.

I wanted very much to witness Payne in action, so the second time we met was clear across the city on a sunny morning in February. Payne was scouting a shoot at the MTA’s 207th Street Shop, a train yard near the northern tip of Manhattan which overhauls carriages, refurbishes HVAC units, and generally reminds its visitors that the trains have to go somewhere at the end of the line. To get there, I went almost to the end of the 4 train, salmoning northward against rush hour traffic for more than an hour, listening to the recording of our first conversation and trying to think of insightful follow-up questions to ask. I had consciously overpacked for the trip: large notebook, small notebook, laptop, voice recorder, not one but two cameras. The day ended up being surprisingly warm, and I had overdressed as well. But I had remembered to wear boots (one of the best things you can do while visiting a factory is wear boots) and felt, overall, reasonably well-prepared.

One advantage of not holding firm to a professional title is that I sometimes find myself cosplaying in a trade that I barely understand. The 4 train ends in the Bronx; I got off at Fordham Road and then walked across the University Heights Bridge in the hopes of catching a glimpse of the 207th Street shop from across the river. It turned out that I could get a view, and so I grabbed my camera, hopped the barricade separating the bridge’s pedestrian walkway from the roadway, and strolled nonchalantly from one side of the bridge to the other, wedging myself into the space between the roadway and the bridge’s seafoam-painted truss members, keeping one eye on the traffic over my right shoulder while I took a couple of pictures of the sprawling complex, framed by nothing in particular and looking drab, cluttered, and unremarkable.

Cars honked unnecessarily as they passed. From there I continued, hopping like Frogger back across the bridge’s four lanes of car traffic, stepping back over the low barricade to the sidewalk, and continuing westward. On the Manhattan side of the bridge I walked past a few large construction sites, then climbed up the steep east side of Inwood Hill to the coffee shop that Payne had suggested we meet at.

Even with this miniature field trip I had more than an hour to kill before Payne and I were set to meet, and by the time he walked briskly up it was almost hot outside and I was eager for the adventure to come. Payne held a conspicuous old FreshDirect bag under his arm; in it were two hard hats and two pairs of safety glasses, which he showed me with an air of conspiracy. Payne lives in Inwood, and his eyes darted back and forth across the street knowingly. I imagined them like spotlights, searching for something to lock onto, but the streetscape seemed to be one that he was familiar with, nothing of note to discuss. We walked past an entrance to the A train, and suddenly something clicked, and without pausing he turned and pointed to an old cast iron pole sticking out of the curb, informing me with reverence that it was one of the last remnants of the city’s network of gas streetlights. It was a clear, dry winter morning, and the scene was undersaturated, blown out. The streetlight pole, painted filthy yellow, was an unremarkable part of a messy setting. But for a moment I imagined Payne’s spotlights on it, and I could see it, and the engineered system that it was once a part of, in all of its honorable and technological glory.

For most of Manhattan, Tenth Avenue is on the far west side of the island; south of Central Park it has no subway lines at all, and it often feels windswept and semi-forgotten. But Manhattan drifts westward the farther uptown you go, and Inwood exists almost entirely to the west of 10th, leaning hesitantly away from the rest of the city and into the Hudson River. The 207th Street shop is on the east side of 10th Avenue, in a low-lying industrial area that must have been marshland before the city grid was drawn up. Payne and I picked our way through construction at 10th Avenue, the 1 train rumbling on elevated tracks above us, and walked up to a soft blue door in the middle of a huge brick facade. We entered into a small and decidedly industrial vestibule; identification was requested and proffered. Payne texted the MTA employee who had scheduled a meeting with him, and while the security guards decided whether we could enter, Payne took out his phone and showed me what he planned to scout that day. His energy was slightly nervous, and I got the sense that his nerves were more attuned to the politics of the situation (the MTA isn’t required to let photographers shoot their maintenance facilities) than they were to the technical aspects of the photographs he was scouting.

It’s a little bit unclear what I can write about our visit, or the negotiations of which our visit was a part. I have, however, been party to similar negotiations in the past: At the same time Payne was pitching his piece on the MTA’s overhaul shops to the New York Times, I was trying to convince the MTA to allow me to reprise a tour of their Coney Island facility — the other half of the 207th Street shop, separated from it by about thirty miles of railroad track. This was the early months of 2020, and I got as far as scheduling a date that April; it was then canceled due to Covid, and when I attempted to reschedule it a year or so later, my MTA contacts told me they couldn’t do so. Payne’s project also stalled during the pandemic, though he seems to have found utility in the extended timeline, using it to shift its scope from one focusing on the long-awaited retirement of the iconic R32 subway car to a broader profile of the MTA’s maintenance efforts.

It is one thing to produce a photographic elegy for an icon of the New York City Subway system, but it is an entirely other thing to give New Yorkers an inside view of the institution that maintains the subways. Moving from the former to the latter — in the middle of a pandemic and not long after the MTA’s “summer of hell” — may not have simplified Payne’s job, and it occurs to me now that the work of gaining entry to sites like the 207th Street shop might play a bigger role in Payne’s output than any amount of lighting, lenses, or shoe leather. Payne acknowledged this much in an interview earlier this year: “I luck out because I manage, with persistence, to get into places that really haven’t been photographed before. I don’t look at my photographs and think ‘This is technically amazing.’ I’m just thinking that people haven’t seen it.”

Of course, Payne has photographed the 207th Shop before; he’s been there multiple times over the past four years, having gotten on drop-by-whenever terms with the shop’s management team. He seems totally comfortable with these people during our visit, slipping easily into jargon and attempting, with moderate success, to remember everyone’s name. When we sit down for lunch after leaving the 207th Street shop, he speaks with admiration about them, describing their career trajectories and personal qualities in glowing terms.

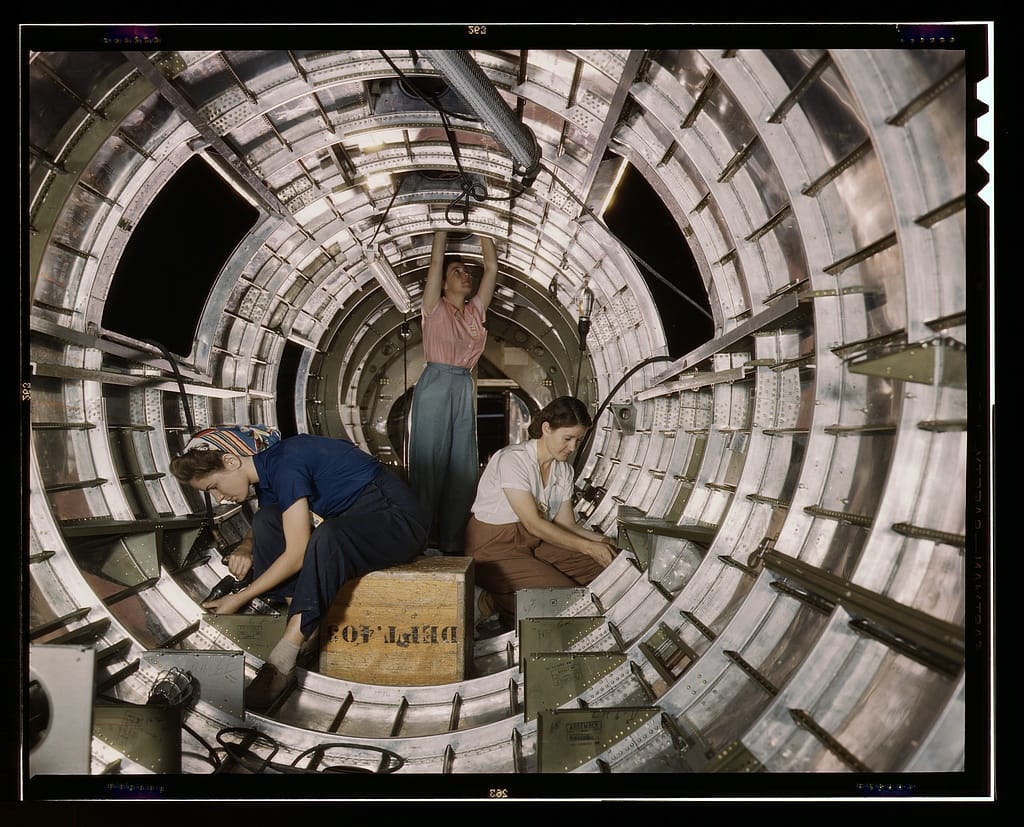

Payne lights these people so that they glow, too. In this respect he follows in the footsteps of photographers like Alfred Palmer, who Payne references in the afterward to Made in America. Palmer, who was hired by the Office of War Information in 1941, had previously worked in advertising and employed decidedly high-touch methods, bringing makeup, strobe lights, and over-the-top staging to a photography program that had previously been more spontaneous and serendipitous. Where many of his contemporaries produced sparse and understated work (Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Russell Lee all worked under Roy Stryker at the Farm Security Administration, the predecessor to the Office of War Information), Palmer’s WWII-era work sometimes seems to bludgeon the viewer, making little pretense about its patriotic intentions. As Beverly Brannan, a curator at the Library of Congress, later described it, Palmer’s work was “beautifully lit, beautifully composed…He used lots of lights, wanted his product to look good, wanted people to buy whatever it was that he was photographing… but some of Alfred Palmer’s pictures are so staged as to stretch the imagination.”

Stryker, who managed the production of hundreds of thousands of federally-funded photographs between 1935 and 1943, would later claim that photography should be thought of as “the corollary, the assistant, and the helper of the [written] word.” But even when they verge into the ridiculous, the work produced by artists like Alfred Palmer is striking, evocative, and conceptually rich, and I imagine that the Office of War Information’s photography was as effective as any of the propaganda the US has ever attempted.

I asked Payne about this word — propaganda — and the relationship he has with his subjects’ commercial and political interests. He did not equivocate: His work is only possible if the factories he visits come out looking good, and when Payne shows up, it’s with the intention of promoting them as best he can. “I feel an immediate connection and responsibility to show them in their best light,” he told me. “It doesn't really do anyone any service if you're not invested in it, and even at factories that I already think I know a lot about, I still go there and am just amazed at how much I don't know. It's thrilling, and hopefully my excitement rubs off on my subjects.”

For as nostalgic and purposeful as Payne’s work is, he’s also acutely aware of the business context in which it exists. For a 2018 piece in Oculus, Payne visited a brick molding factory in Massachusetts. “They made bricks the old fashioned way,” Payne told me. “It’s really cool, and I was getting all romantic about it — ‘aw, these beautiful bricks you make, and every one is different’ — and the factory manager tells me ‘I’m not in the business of making bricks. I’m in the business of making money.’ That stuck with me, you know, that all these places are economically motivated.”

Back in the pizza shop, Payne had asked if he could review the transcript of our conversation before it was published, and after our visit to the 207th Street shop he asked me what the goal of my piece was. It was a natural question, but I was caught a bit off guard. “I'm interested in observing work, and the balance between the aesthetics of workplaces and the explanatory power of your photography,” I stumbled. “I mean, you’ve scouted and re-scouted the 207th Street shop three times, revisiting and re-experiencing this little corner of the world and trying to find a way to make it accessible.”

I paused, then backed up: “There are people who live around the corner from the 207th Street shop but don’t understand at all what happens there. But you photograph it, and the photos are published in the newspaper next to news about the Supreme Court, or Taylor Swift, or whatever. And all of the sudden, the 207th Street shop is being presented as, like, part of the fabric of life. Which, of course, it is.”

To leaf through Made in America, the main takeaway from Payne’s industrial photography is the obvious but elusive fact that stuff comes from somewhere, and that the birth of even a commonplace object can be bizarre and surreal. A pink paint roller is made from pink wool; okay, fine, we might have guessed as much. But as Payne shows us, that pink wool, when being dyed and processed at a factory in Massachusetts, fills every corner of its birthplace with ephemeral wisps of pink fuzz. In this light the products he photographs are allowed to exist across their many states. Payne shows us heaps of raw woolen clumps being separated and cleaned. He shows us serpentine coils being vomited from an ancient machine. He shows us thousands of threads, all oriented toward a single vanishing point, and he shows us a rainbow of bobbins binned and stacked and ready for sale. With every turn of the page, the reader imagines the same fiber metamorphosed — all the while shedding tiny parts of itself, which then accumulate into cirrus-like filaments at step after black-boxed step.

But I’m not really sure what to take away from Payne’s role as an observer of manual labor — partly because the labor I observed him doing was so subtle and political. We were not visiting the 207th Street shop to take photographs, after all, but to make sure Payne still had access to and trust from the MTA.

I don’t know what Alfred Palmer’s relationship with the Douglas Aircraft Company was, but I do know that between 1940 and 1943 he managed to produce at least forty-six hundred photographs for the Federal Government. Payne, on the other hand, had been “dragging this out for four years” by the time we visited the 207th Street shop together. His editor was “going to get annoyed really soon. The draft's written, but I want to redo one shot, looking down on the cars… If I go there, and I don't nail it, it's a shitty feeling. It's like going out on a date, and you know that date's not going to go well.”

There were a few moments at the 207th Street shop when I wasn’t sure the date was going to go well. We had been let into the building and led into a low-ceilinged office area. It had the appearance of a construction site office, adapted maybe from a prefabricated trailer that was dropped on the floor of the factory. As we entered we were confronted with a clutter of desks, each of which was cluttered with large stacks with paper. Through this makeshift office area we entered a conference room, which was appointed with mismatched furniture and decades of randomly arranged relics. An American flag, folded and framed, was propped on a ledge. A grandfather clock stood, stuck in time, in one corner. I am here to assist Christopher Payne, I reminded myself as I squeezed into the opposite corner, glancing at the handwritten “NYTimes” on my visitor badge and noticing that it would be physically awkward for me to exit the room if that was requested. Every other seat in the room filled up: Payne to my immediate right, with various MTA employees wrapped around the table past him. And all of the sudden I realized that I had entered into a meeting between two of the most important institutions in New York City: The Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the New York Times.

Throughout my time with him, I had gotten the sense that Payne was not accustomed to being interviewed. This is fair: I’m not used to being interviewed either, and nor am I used to interviewing someone else. Payne must have sensed this (towards the end of our first meeting, he had asked what it was I did for a living) but he rolled with it, graciously making himself available for two and a half hours of one-on-one conversation and agreeing to let me act as his assistant during a pivotal moment in a four-year-long project. When I had suggested tagging along, I thought I would see him composing photographs, setting up lights, observing and documenting manual labor. But as I sat down next to him in the 207th Street shop’s dingy conference room, I realized that this was the place where I would witness him at work.

There were multiple conversations going on at once. Someone mentioned maintenance issues on the open-gangway R211 cars running on the C line; someone else noted that the total headcount at the MTA’s Coney Island shop is around eight hundred people. Payne had already announced to the room that there were just “a couple more things I wanted to get” for the piece, but the meeting didn’t properly start until it became clear that this entire project, four years in the making and just one or two photographs away from completion, was a source of some anxiety at the MTA. Somebody wanted to know what the goal of the piece was; the question was natural, but within the context of this meeting (the New York Times doesn’t tell people what they’re writing before publication) it could not be answered. To dissipate the tension I was feeling, I took notes — nothing insightful or even particularly detailed, but it felt good to be using my hands, doing something mindless and mildly useful.

But whatever tension I was feeling, it did not seem to attach itself to Payne. Where I had heard confrontation — What is your goal here? — he seemed to hear a narrow, technical question. “The only reason we haven’t published yet is that I keep thinking of new things to photograph,” he said casually, then pointed across the table at the shop’s supervisor and chuckled. “Plus, I like bothering him every year.” At this, Payne pulled his phone out and showed everyone a picture of Gay at her workstation, and again I imagined him looking at a messy scene and finding something interesting to shine a spotlight on. The room condensed, necks craning in to catch a glimpse of whatever it was that Payne was gesturing towards, and all of the sudden we all knew what the goal was. Oh, sure, Gay. She’s here today, let’s go talk to her.

And that’s what we did.

In the introduction to Made in America, Simon Winchester writes about industrialization, consumerization and the abstraction of knowledge and skill that occurred in the past few centuries. Before factories, it took forty-three individual craftsmen to make a block for the British Navy; in 1803, with the invention of Henry Maudslay’s block-making machines, that number was reduced to ten. Winchester writes of this transition with reverence, but he also suggests that Made in America “poses questions which, given the uncertain condition of our present-day planet, sorely need to be addressed.” I asked Payne what these questions were, and his answer mirrored something that he had written in the book’s afterward: “My photographs are a celebration of the making of things, of the transformation of raw materials into useful objects… They are also a celebration of teamwork and community…These are the people who make the stuff that fuels our economy, and in this time of social polarization and increasing automation, they offer a glimmer of hope.”

But I think that Payne himself is the one who offers a glimmer of hope. The factories he visits are complicated, complex, kludgy. Factories take knowledge away from craftspeople and turn it into bureaucracy and institutional anxiety. Factories pollute our waterways. Factories take razor-sharp lathe swarf and try to convince us it’s jewelry; factories enlist workers to help someone else fulfill their dreams. But then Christopher Payne comes in, and he crawls around for a few months, and he finds parts of the factory that we can be purely and unabashedly proud of. I don’t think that Payne’s work is asking questions at all; he’s just taking something messy, and pointing a spotlight on the honorable parts. And, to be honest, I think that’s probably what we need.