This is a lump of beef suet, photographed on my kitchen counter. Suet is the name for the two irregular torpedoes of hard fat found in the thoracic cavity of a cow, one wrapped around each kidney. It feels like a candle wrapped in dried gossamer. This piece weighs about 1200 g and is approximately a quarter of what you’d obtain from a small cow.

Suet only really appears in my kitchen when November meets December, because it’s a key ingredient in a classic plum or Christmas pudding (as well as Spotted Dick and virtually any other steamed pudding you can name). I can’t think of any other use for it, though I’m old enough to remember when tallow – rendered suet – provided the je ne sais quoi in McDonald’s french fries.

That I have no use for tallow is an accident of modernity. Up until the early 19th century, essentially all oils and fats that humans used – whether as food, fuel, lubricant, or finish – were derived from plants and animals.

Were I presented with that lump of suet in 1824 instead of 2024, I would, after chopping some into my pudding, have rendered it for tallow and eaten the brown crackling (called greaves) in the rendering pot. I’d have molded the tallow into candles, or used it to grease my sewing thread or my rifle or the axles of my cart. At a larger scale, we used tallow for rolling steel (and still do) but lard for general metalworking. Mutton tallow was preferred to beef tallow in textile manufacture. Beginning in the 1550s, tallow candles and farthing dips were gradually displaced by whale oil, especially sperm oil, which remained liquid even in the depths of winter, but both remained in use into the 1800s.

Before we understood lipid chemistry, the pharmacopeia of naturally occurring fats provided myriad technological opportunities. Nature, it seemed, offered a substance for every conceivable need, awaiting only enterprise and exploitation (we also still believed in manifest destiny and the white man’s burden).

But humanity was also limited by the affordances of naturally occurring fats – the pharmacopeia was also a kind of planetary boundary. Modern, industrial-scale processes for manipulating the chemical structure of fats, for turning one lipid into another (fractionation, hydrolysis, and hydrogenation) were only commercialized in the late 19th century, having been enabled by the transition to fossil fuels.

Today, industry assumes that oils and fats are plastic; that we can make nearly any lipid behave nearly any way we want. We went from mining nature for particular fats, to mining fats for their components.

It wasn’t apparent at the time, but the invention of margarine in 1869 marked a turning point. Napoleon III had offered a prize to the person who could devise “a substitute product for ordinary butter, cheaper and which keeps well, for the navy and the less well-off classes,” which Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès, a French chemist, won with a mixture of tallow, water, skim milk, and sodium bicarbonate.

So much comes together in this moment. The idea of mass luxury – that everyone, down to the lowliest swab in the French navy, deserved something unctuous on their bread; a food created to prop up a social structure that had pulled people off the land; an empire putting its weight behind the idea that one fat could be made into another. This wasn’t substitution, like using chicken fat when a recipe called for lard – this was transmutation.

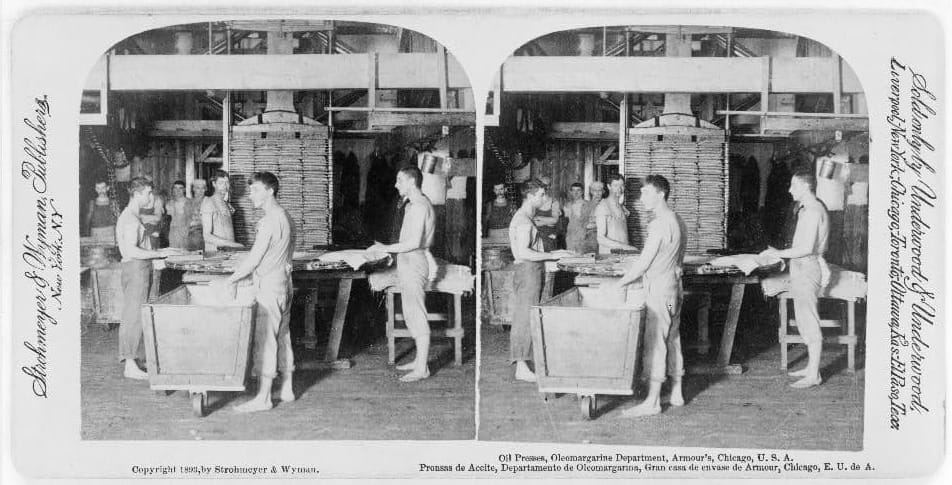

Mège-Mouriès’ process began with the fractionation of tallow. He melted suet, then added digestive enzymes (first macerated sheep’s stomach, later chopped cow’s udder) to remove other tissues, yielding pure fat. A fraction of the fat was then allowed to recrystallize, then he pressed the whole mass to extract the semi-solid fraction, and emulsified that with the other components to obtain a solid, or at least semi-solid, white mass. The emperor’s chef might have called it tallow mayonnaise.

This was not a groundbreaking feat of fat chemistry. The basic process for fat fractionation was well understood, and had been commercially applied in the whaling and soapmaking industries. The same principle underlies the fractionation of palm oil today; it’s one of the battery of techniques that enables us to derive functional substitutes for canola oil, butter, and beeswax from a single fruit.

Mège-Mouriès named his creation oleomargarine, the “margarine” being derived from the Greek word for “pearl.” In spite of its aspirational name, margarine took a while to get going. The French never really took to it, though nearly all of Protestant Europe (the parts with a persistent reputation for terrible food) did. Mège-Mouriès licensed his invention to Jurgens, the Dutch company that would, several mergers later, put the Uni in Unilever. Jurgens immediately began improving the process and the product, beginning by introducing a soupçon of yellow coloring so the product would more closely resemble butter.

Color was the least of their problems. The real difficulty lay in solving problems of flavor and what a 1940 paper called “that almost indefinable but all-important character of texture.” Early versions of margarine, according to this author, were “inclined to be unpleasantly greasy, to stick to the knife, and to spread in a manner unattractive to those used to butter.”

The key to the problem of texture didn’t appear until 1902, with the invention of a commercial process for the hydrogenation of liquid fats. Hydrogenation might be familiar to some people as the process which turns soybean oil, naturally liquid at room temperature, into stiff, creamy Crisco. The process literally turns one lipid into another. By increasing the degree to which fat is saturated with hydrogen atoms, it changes the shape of the constituent fatty acids, raising the temperature at which the fat melts.

“That almost indefinable but all-important character of texture” is determined to a significant degree by how fat melts when exposed to the heat of the human body. It’s almost impossible to quantify, but it’s also a key determinant of whether we’ll enjoy, and by extension buy, any fat-bearing food or cosmetic. The human body is both a terrible assaying device and the only one that matters.

I want to end by unpacking this nexus a little.

It feels spurious to argue that fat hydrogenation wouldn’t have taken off without the demand for margarine – it’s too useful a process. But a guaranteed buyer is a great spur to research and development, and the margarine industry was a great source of guaranteed demand, because margarine was an edible fat that had to be engineered. The amount of fat we need for fuel or industrial applications is always being reduced by the introduction of more efficient technologies, but demand for edible fat increases with population, and the global population is still rising.

The most important characteristic of an edible fat is acceptability – whether humans will want to push it past the chemical detectors in our mouths and into our squishy meat sack bodies – and our bodies are both highly sensitive and easy to fool. You can’t trick an industrial process. Lubricate a rolling steel mill with vegetable oil instead of tallow, and it will seize. But humans will happily accept a mix of tallow, skim milk, sodium bicarbonate, and water instead of butter, as long as it feels right in the mouth.

Margarine, perhaps more than any other substance, taught us to stop thinking of fats as distinctive and immutable natural products and to start thinking of them as invisible inputs instead – a molecular vellum on which to write our human desires.

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now