A new life for old landfills

On a brisk spring day in April, I walked across the vast expanse of the shuttered Phoenix Golf Links course on the south side of Columbus, Ohio. Its artificial hills, visible from the adjacent highways, sculpt respectable fairways out of a formerly discarded landscape. On the periphery, batches of black pipes flare off methane gas, part of an extensive network of pipes and gas wells that link the overgrown grassy surface to the garbage heaps below layers of dirt and clay. This forgotten corner of Columbus is, by all measures, the ideal location for a solar farm.

The site is wedged between three highways – I-71, I-270, and State Route 104. It has a series of boisterous neighbors that line its northern and eastern edges, most notably a limestone quarry, Jackson Pike Water Treatment, Liberty Tire Recycling, and the forced home of 1,400 imprisoned individuals at the Franklin County Correction Center II. Common to most cities across the country, it’s a designated area for the discarded.

Opened in the late 1960s, the .73 km2 Model Landfill served as the city’s landfill until its closure in 1984, when it was then capped with dirt and a layer of clay. In the 1990s, it was transformed into the Phoenix Links golf course, reshaping one form of pollution – landfills being responsible for 15% of US methane emissions – into another, as golf courses use thousands of pounds of pesticides that can contaminate local water supplies. The Solid Waste Authority of Central Ohio (SWACO) was tasked with capturing landfill methane to be converted into energy, but when the golf course closed in 2014 and the methane levels from the capped landfill dwindled, the former landfill turned golf course became barren, the abandoned site standing plainly visible to highway traffic. Today, the grass is overgrown and the asphalt paths are cracking. However, the transformation of the former landfill turned golf course has only just begun.

By 2016, SWACO had exhausted the fund for maintaining the closed landfill, which drains roughly $400,000 annually. Since then, they’ve relied on revenue from their active Franklin County Sanitary Landfill. The lack of funds drove SWACO to hire the consulting firm Arcadis to study potential uses for the land, analyzing its unique geographical conditions and looking at what other capped landfills across the country have tried – bike trails, paintball fields, land for organic farming, and, most enticingly, a solar farm.

In 2020, SWACO announced they would partner with BQ Energy to build a .7 km2 solar farm on the former Model Landfill site. The Columbus Solar Park, as it will be called, is scheduled to be operational in 2023 where the 50 megawatts of electricity, enough to power 5,000 homes a year, will be bought locally by AEP Energy and the City of Columbus to help fulfill the city’s green-energy aggregation program. While the Columbus Solar Park won’t curb emissions from the landfill, it will provide 50 megawatts to the city’s grid that won't be from coal or gas. And while it won’t get anywhere near powering a whole city, it will nonetheless inch the city closer to reducing emissions by 45% by 2030 and potentially set a precedent for capped landfills across the state. Four other landfill solar projects are already planned in Ohio through BQ Energy alone. Many of those closed sites sit empty next to urban centers, soaking up the sun while draining taxpayer money. As Paul Curran, the Managing Director at BQ Energy says, “One of the challenges is to generate more electricity near cities and coincidentally an awful lot of landfills are located near where people live.”

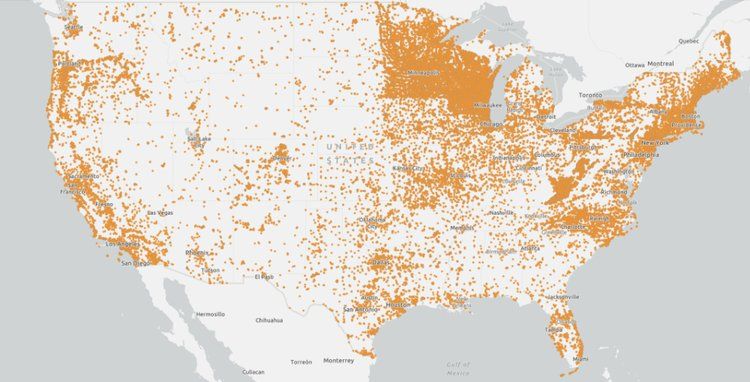

The key to building enough clean energy infrastructure to reduce emissions involves one essential resource: space. Specifically, the purchasing or leasing of private and public property. The EPA tracks over 190,000 brownfields, landfills and mine sites that have renewable energy potential, totalling almost 162 000 km2. This is more than twice the estimated area needed to run the US exclusively on solar, which the National Renewable Energy Labs puts conservatively at 55 000 km2. Of those 190,000 sites, more than 18,000 are landfills. According to a report by the nonprofit RMI, closed landfills could supply an estimated 63 gigawatts of energy to America’s grids, almost doubling the current capacity of 89 GW and could supply enough power for 7.8 million homes or the whole state of South Carolina. Space, especially discarded and exploited space, is an abundant resource in the US.

There are many feasibility factors with site conversion: the age, slope, electricity infrastructure on-site or nearby, the concerns of the surrounding community. In the case of Columbus, the landfill checks off all these boxes and the EPA marked it as having potential for solar, wind, biomass, and geothermal energy production. It’s less than a half mile away from the nearest substation and transmission line, a prime location for energy production. Its older age would normally be an issue since it wasn’t common practice to cap landfills, but the Model Landfill was capped with clay after its closing. Its distance from residential areas reduces community concerns. Once the added golf course hills are bulldozed, the landfill slope will be minimal, making all of its geographic characteristics ideal for energy production.

For a feasible location like the Model Landfill, the technical transition is often pretty minimal according to Michael McNulty, Project Lead for BQ Energy. Many of the potential issues involve water. When dealing with a landfill, it’s essential that water stays on the surface, otherwise the decaying, methane-producing garbage heap risks being transformed into a toxic lake, poisoning the land and leaking into waterways. Therefore, it’s important that the posts that hold the solar panels above the landfill don’t let surface water in. The solution, ironically, is the same adsorbent used in oil drilling: bentonite. In oil drilling, the absorbent swelling clay is poured as “drilling mud” to keep the drill bit cool. In landfill solar farms, it’s used as a groundwater sealant, forming an impenetrable layer of protection against surface water.

Since American cities like Columbus are left on their own when it comes to switching to clean energy, they often have to resort to partnerships with private companies. The Columbus Solar Park will generate an estimated $12 million over the 25 years for SWACO, or $480,000 a year, ending the problem of finding $400k for upkeep. Public-private partnerships are pitched as low-risk compared to publicly-owned endeavors, which falls on open ears after experiences like the controversial and since demolished city-owned incineration power plant built in the 1980s that cost the city $400 million. This legacy has led SWACO to take a defensive stance, maintaining that BQ Energy is taking on all the financial risk. Public-private partnerships are almost essential for an underfunded public sector scavenging to survive, often merging with the private forces that the state is supposed to keep in check. But the Columbus Solar Park has earned the support of local climate activists like Simply Living's executive director Cathy Becker, who's been a frequent critic of local climate policy. Considering the solar project, she says, “I'm really proud of the city for doing this.” It’s seen as a relatively mutual partnership in this case, whereas other examples in the city, specifically regarding private developers, tend to heavily favor the private sector.

As American cities look for large spaces to build sites for clean energy infrastructure, even in their shortcomings and uncertainty, it could be that the best location for the projects is on top of the city’s old landfill. Their proximity to city centers offer a prime location to generate and supply clean energy from the surface of an otherwise lifeless landfill. The transition to solar and wind energy, a process that sometimes feels abstract as we consume electricity isolated in our homes and work, could also include a very visible spatial transformation of waste zones in our cities. The overgrown golf course next to the highway, the city’s area of the discarded, will soon be a vast field of glimmering solar panels, standing proudly above the buried waste.