You can’t write about palm oil without writing about personal care products, and you can’t write about personal care products without writing about William Lever, the “Lever” in “Unilever.” Trying to do so is like writing about social media without mentioning Elon Musk: In some sense all the important stuff was done before he came on the scene; in another sense he encapsulates everything that was important.

Lever’s great contribution to humanity was being the first person to put soap in a box, even though he didn’t invent a single goddamn one of the processes involved in doing this. He was merely a megalomaniac and a marketer, but when he died, obituaries compared him both to Napoleon and to Henry Ford.

Lever was born to a Scottish grocer in Liverpool in 1851, at a time when grocery was a skilled if somewhat scattered profession. Soon after Lever’s birth, his father transitioned from retail grocery to wholesale, and Lever joined the family firm at the age of 16. Initially, he expanded the company, setting up new branches and direct relationships with suppliers in Ireland, but eventually decided to specialize in soap.

A grocer had to know everything from how to blend tea to how to cure ham, how to store each of his wares in optimum condition, and then break it down for retail sale – including soap, which was bought from wholesalers in large blocks, then sliced or flaked to order. In theory, the customer need not know or care who made their soap, since they could rely on the grocer’s advice and expertise, and the grocer himself could rely on a wholesaler. Manufacturers dealt solely with wholesalers; consumers barely entered their worldview. By wrapping pre-cut bars of soap in vegetable parchment and enclosing them in branded boxes, Lever not only created a product that a grocer could simply put on a shelf, he established a direct relationship between manufacturers and consumers.

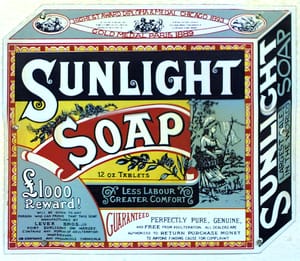

That soap was called Sunlight. Based on a class of soaps known as “self-washers” because they lathered easily, it was originally one of over thirty Sunlight soaps – Sunlight XXX, Sunlight XX, Sunlight Mottled Brown, etc. Most of these weren’t what we’d call soap today, because we didn’t yet have a category of “detergents,” though the notion of a “toilet soap,” i.e. soap for the body, was emerging. According to the founding myth Lever propagated, he decided to make Sunlight Self-Washer his flagship product after a Lancashire washerwoman told him “I mun ha’ some more of yon stinkin’ soap” (the original formulation sweated drops of rancid oil, giving the soap a characteristic aroma, though the oil washed off during its first use).

When Lever decided to go into soap manufacturing himself, in 1884, he engaged a staff of chemists to tweak the formula of Sunlight Self-Washer (formerly manufactured for him by Joseph Watson & Sons), arriving at a blend of 41.9% palm kernel or coconut oil, 24.8% tallow, 23.8% cottonseed oil, and 9.5% resin, plus a blend of perfumes including rosemary oil.

But Lever’s soap in a box was merely the pointy antenna atop a Chrysler building of real scientific and technological development, most of which happened a few short decades before he appeared on the scene.

Here is a list of things Lever didn’t do:

- He did not invent soapmaking. I’m inclined to forgive this one, because soap is older than recorded history.

- He was not even the first person to commercialize palm oil soap. Palm oil soap had been in use in Africa since antiquity, and early European arrivals actually traded for the soap as well as the raw oil. Once exports of palm oil started arriving in Europe in the late 18th century, soapmakers adopted it enthusiastically. It lent an appealing yellow color to their soaps, its faint scent of violets meant they could cut back on the use of other perfumes, and palm oil’s reputation as an emollient and a medicine made palm oil soap a luxury – to the point where it was counterfeited, tallow soaps dyed yellow with other colorants. But imports of palm oil grew rapidly, so much so that by the 1820s, some soaps were made entirely with palm oil, which had become cheaper than tallow. Liverpool displaced London as the UK’s center of soap manufacturing, mostly because that’s where shipments of palm oil from Africa were unloaded, and every soap-boiler in Liverpool relied on palm.

- He didn’t make any breakthroughs in chemical manufacturing. The other reason soap factories flocked to Liverpool was that a chemical plant there churned out massive quantities of soda ash, soap’s other essential ingredient. By this point, Europeans had deforested their continent to the point where wood ash was too scarce to provide all the alkali they needed. Louis XVI offered a prize (there’s clearly a pattern to technological development in France) to the first person who could synthesize the stuff, and Nicolas Leblanc came up with what sounds like a frankly bonkers process involving sulfuric acid at 900ºC. The Leblanc process came with some drawbacks – it released clouds of gaseous hydrochloric acid, and produced an almost equal weight of solid waste known as “galligu,” which was spread around nearby fields, where it released hydrogen sulfide (which gives rotten eggs their smell) as it decomposed. Fortunately, by the time Lever started his soap factory, the Leblanc process was being replaced by the somewhat less hazardous Solvay process (which, obviously, Lever didn’t invent either).

- He was not the first person to make soap for sale in bars. According to Lever himself, “I was the first to advertise extensively a tablet soap although makers had produced tablet soaps prior to my commencement in 1884, but they had not pushed them and they were little known…. Then their tablets were wrapped with ordinary common paper and the sweating of the soap destroyed the paper.”

- He did not invent cardboard, wrapping paper, or the use of cardboard as packaging. The first commercial use of a paperboard package is generally dated to 1817. While most references suggest the process of manufacturing such boxes was invented in England, the first product packaged in cardboard seems to have been a German board game. Flaked cereals, the killer app for such boxes, only came along in 1894.

Despite my mockery, there’s something deeply true about Lever’s story. He’s the kind of character who we’d have had to invent if he didn’t exist, because his story is the story of how the modern consumer was born.

I write this in spite of the fact that he wasn’t even the first person to create a consumer brand, or the first manufacturer to publish advertising directed at individuals. Tobacco and tea were already being sold in what we would recognize today as consumer packaging. Some of Heinz’s 57 varieties of preserved foods were already on the market. Coca-Cola and Procter & Gamble, among other American companies, were certainly engaged in the practice already, and indeed Lever referred to the US as “the El Dorado of commercial prosperity” and maintained scouts in the US to keep himself informed of the latest developments in advertising. In a way all Lever was, was in the right place at the right time. He stood atop not just an edifice of technology that he did not invent, but a mountain of socioeconomic change that he did not cause. Consider all these other things William Lever didn’t do:

- He was in no way responsible for the exploding consumption of soap in Britain, which grew 15x between 1800 and 1900 – an approximately 5x increase per capita, from 1.6 to 7.7kg per year (much of this during the first quarter of the century), coupled with a trebling of the population. That was a result of the industrial revolution, which not only fueled demand by making sure everyone in Britain was coated in soot, but also supplied it, propagating the chemical processes, trade routes, and industrial organization needed to increase the production of soap (and many other goods) on this scale. In Britain, the price of soap fell by half between 1821 and 1846 – partly because of the falling price of palm oil, and partly because the first soda ash plant (using the Leblanc process) came online in 1824.

- He didn’t shape the the great enrichment. Lever entered business at a time when large chunks of the population of Britain (around 70% by 1900) began to enjoy a disposable income. At the same time, urbanization and industrialization – both of which contributed to disposable income becoming a mass phenomenon – created conditions in which people needed to wash more often, and also uprooted them from rural communities which fulfilled most of their needs, thereby causing them to need to buy things with the cash in their pockets.

- And he didn’t create the mores and obsessions of Victorian Britain (though he certainly amplified and propagated them): the belief in progress and the civilizing mission; the phobia of dirt and the working class body; the obsession with mental and physical purity; and the consequent fears around adulteration, which attached themselves to every item in the grocer’s inventory.

Swept up in the second industrial revolution, workers in Britain for the most part decided to use their newfound purchasing power to improve their lives: They bought convenience, domestic harmony, and ultimately, respectability. Convenience is in some sense a fact – there are ways of doing things that just take less effort. But respectability is a more emotional construct, and what Lever did better than any of his peers was to offer this intangible for sale. He demonstrated what you could accomplish by selling a little bit of sunlight to a lot of people.

I think Lever dominates the imagination (or at least my imagination) because everything else about this moment is so diffuse and hard to pin down. Technological developments and legal maneuverings and systems of belief, all coming together like fronts in a storm. Lever by contrast is human: a small, slightly rotund Scotsman, with eyes that look blue even in sepia photos. Even if Lever’s success owes much to historical forces, Lever himself still marshaled them, so when we look at him, all of those forces seem a little clearer.

Direct quotes in this essay are drawn from Brian Lewis’ biography of William Lever, So Clean: Lord Leverhulme, Soap and Civilization; in most cases, Lewis was citing primary material found in the Unilever company archives. The archives are fascinating in their own right, and they have an instagram account. I’ll also call attention, as I did in the first issue in this series, to Jonathan Robins’ Oil Palm: A Global History. Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible.

Love,

tw