Here’s a fad that I lived through, and even played a small role in: Mass customization.

The idea, which according to the Google Books Ngram Viewer peaked around 2009, was that physical products would be manufactured on-demand and tailored for individual customers’ specifications. Someone purchases a widget and includes notes about its size, shape, or (I don’t know) squishiness; the manufacturer adjusts their tooling, or whatever, and makes a one-of-a-kind instance of the product, shipping it directly to the customer. Apparel tended to be spoken of as well-suited for mass customization; Sols, a now-defunct startup that made 3D printed insoles between 2013 and 2017, was probably the best example of mass-customized apparel before TheMagic5’s hot wire-cut swim goggles launched in 2016.

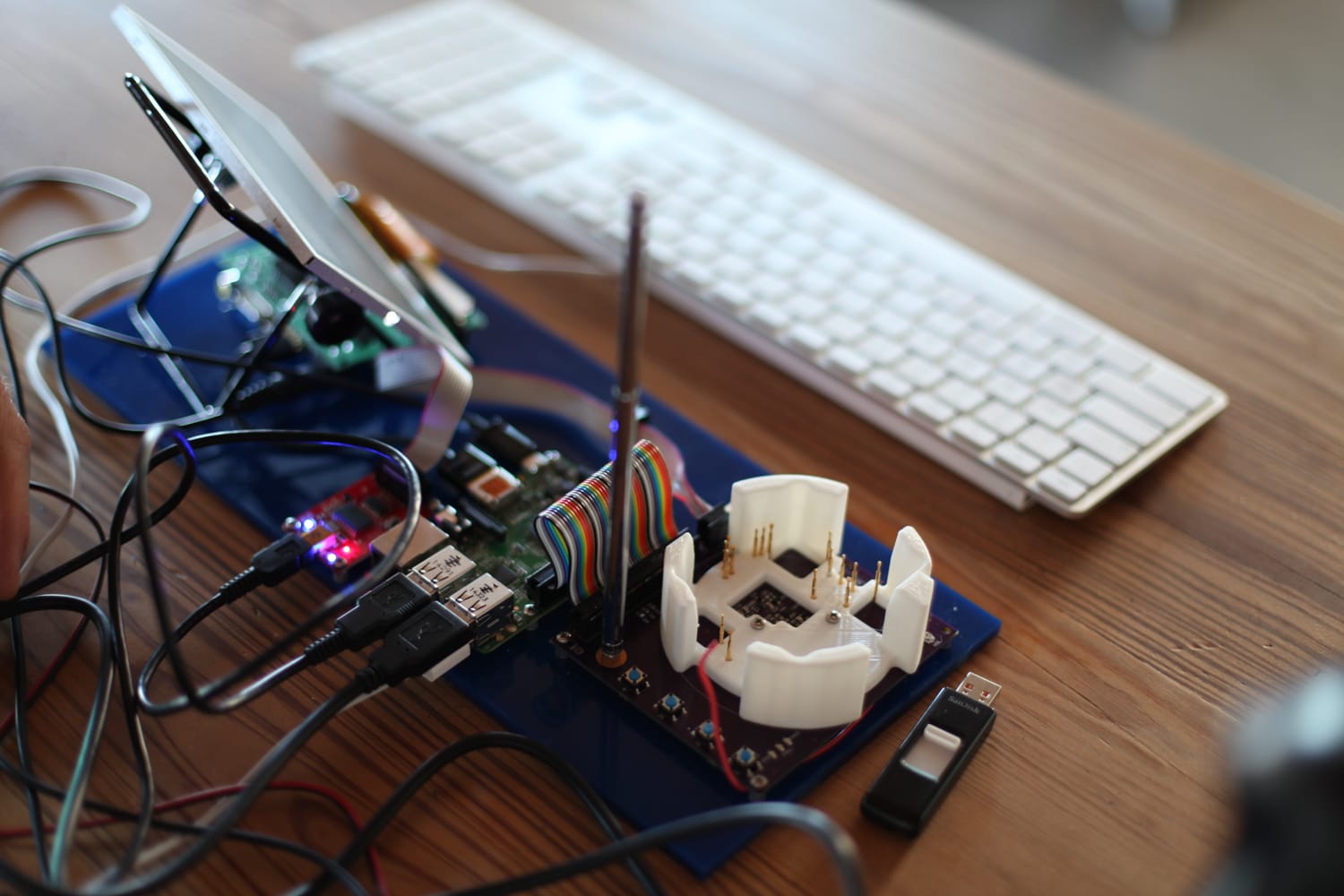

The product that I mass-customized was a piece of consumer electronics called The Public Radio. We had backed into mass customization in a weird way, taking a feature that would typically have been field-adjustable and locking it down. Specifically, we designed The Public Radio — a battery-powered FM radio — such that it did not have a tuning knob and instead needed to be tuned to the customer’s requested frequency during the manufacturing process.

This was silly, but also (you may have to trust me on this, depending on your preferences) kind of clever, and resulted in a cascade of subsequent decisions. For one, we knew more or less out of the gate that it would be impossible to find an overseas contract manufacturer to make The Public Radio; we would simply never reach the sales volume sufficient to justify drop-shipping them, and furthermore our production process was bound to be fairly complex and would require a contract manufacturer that was nimble and driven at least partly by curiosity, rather than purely by scale. In parallel, we knew that The Public Radio was going to be a fairly high-touch product and would probably be priced and marketed to an audience with some disposable income and a sense of whimsy. This led directly to The Public Radio’s second-most notable design feature: We chose to house the radio inside of a squat little mason jar.

I had so many surprising experiences working on this little thing. Between 2014 and 2023 we sold more than ten thousand units; I personally assembled and shipped at least a couple thousand of these. This meant, among many other things, that I also personally unboxed thousands of squat little mason jars, which the manufacturer refused to sell us in bulk packaging — or without the standard canning lids, which we needed to remove by hand and discard. We replaced these with a custom stainless steel part, which I had a progressive die made for. This was fun — a novel manufacturing process for me, and one that’s satisfying to watch — but dealing with the manufacturer, a Taiwanese company that was hoping for larger production volumes than we could handle, proved difficult over time. Shipping these parts by air was expensive; shipping by boat was time consuming; dealing with production issues (which were minor, but super annoying: defects in the brushed surface that weren’t visible until after the protective film was removed; protective film that left a sticky residue behind) was tricky.

What justified these annoyances?

Perhaps the best answer is underemployment. I began working on The Public Radio during a time in which I seemed to be darn near unemployable. I was in my early thirties, and single. I was overqualified for entry level positions in (humblebrag?) basically any industry, but (truth!) lacked the credentials to work on anything of consequence. And so when Zach shared an idea for a product that would probably sell more than zero units – and was simple enough that the two of us could take it on more or less alone – I threw myself at it.

Probably the best lesson I could give (or take) from my experience working on The Public Radio is that a project’s outcomes will likely be shaped heavily by the goals you set going into it. We were clear about our goals: We wanted to ship a product, and we wanted to do so in a way that would allow us to essentially brag about it in public. I believe that these goals were appropriate, both for the product and for my career. But they were not particularly ambitious, and from time to time I have wondered what life would look like had I directed my efforts towards bigger things.

That said, there are any number of little moments that I’ll cherish forever — and little lessons that I’ll never forget. After we had built a couple Public Radios for ourselves, we put them up for sale on a (now defunct) hardware preorder platform called Grand Street. I think we sold a dozen units, which we assembled by hand on my kitchen table. There were a couple of thru-hole components, but most of the printed circuit board assembly consisted of 0603 surface mount parts, which we laid out in the middle of the table and picked-and-placed with tweezers, smearing a little solder paste on the pads with a toothpick first. Once all the components had been placed we’d fry them up on a hot plate that I must have bought on Amazon. I think we had a mortality rate of around fifty percent, but after a night or two of tedious labor we managed to build and box up all of our orders. I had bought some little notecards, and we hand-wrote messages to each recipient, signing the notes personally and including (imagine this!) our cell phone numbers in case of any issues. A month or two later, we received a text message from someone in (if I recall correctly) Kansas, who included a video of their Public Radio alongside some kitschy mason jar lamp things that they had made. It was incredibly sweet, and even if the project had ended there, I would have been satisfied beyond any of my expectations.

But it didn’t end there. Maybe a month or two went by, and on a whim I submitted our not-that-shabby website to 99 Percent Invisible, the design podcast which at the time happened to run ads which highlighted a website hosted on Squarespace. A short while later I got a note from Roman Mars, confirming that he’d be plugging our little mason jar radio’s website. The traffic this resulted in was somewhat unexpected (Narrator: It was also a significant stroke of luck), and we put everything into turbo mode and launched our first Kickstarter a week or two later. At this point we had made friends at Kickstarter’s Design & Tech team, and through those connections we were put into their “Projects We Love” newsletter (Narrator: Ditto). The evening that the campaign launched, my family had gotten tickets to see Derek Jeter’s last home game at Yankee Stadium, and as I, a lifelong Mets fan, cringed at the pageantry, I also found myself frantically refreshing the project page, watching as we surpassed our modest funding goal a few times over.

Everything up to this moment had been kind of a lark — something we had put real effort into, but which we had maintained some emotional distance from. Now we were officially Doing It, and that shift was both energizing and a little sobering. There was no time left for hot plates and hand-written notes; everything needed to mature a bit, professionalize, and most of all get a lot more predictable and consistent. We had made dozens of radios by this point, and in previous parts of my career I had overseen the production of hundreds of similarly complex assemblies, but here we were making twenty-five hundred — a number too small for us to hire anyone else, but too big to accomplish alone.

Managing production of those twenty-five hundred radios was one of the highlights of my creative career. We did it via the proverbial pizza and beer. For a few consecutive weekends we set up shop in an underutilized Soho office that I had access to (Narrator: What?), and invited literally everyone we knew to work for free in exchange for a meal. It was a ton of work, occupying all of my waking time between the end of the day on Friday until the end of the day on Sunday, for about a month and a half. I was by this time working at a boutique management consulting firm which was on the verge of implosion. Not all of my coworkers showed up to assemble radios, but many of them did, and I believe that I wasn’t the only one for whom the experience was cathartic and energizing. This is, perhaps, the most widely applicable lesson that I can draw from the entire project: It’s good, every once in a while, to get in a little over your head and be forced to ask every single person you know for a favor.

We finished this first production run with a few thousand dollars in our bank account. It was at this point that we elected to visit our Chinese suppliers — companies that we had relied on completely, but which we didn’t have the time or the foresight to visit before our drop-dead ship date. My employer was teetering as we left for Asia, and I returned to collect my severance payment and begin the process of finding a new job. At that point — this was about eight weeks after we had shipped out radios to our Kickstarter backers — The Public Radio didn’t really figure in my broader career plans. We were basically out of inventory and totally out of money, and while we pulled the whole thing off with a very low failure rate and a remarkably professional-looking product, it was all still a little too half-baked to expect to derive any income from it. (We had reimbursed ourselves for expenses incurred in the course of completing the Kickstarter, but were paid nothing for our time.) Plus I was getting married in a month or two, and would have a child within a year and a half. So I joined a startup (a separate story) and we agreed to put The Public Radio on ice.

One of the delights in getting older is to perform the same action at different stages of your life, noticing both the familiarity and the foreignness that comes with time. Last week, for instance, I took a long bike ride on a bike that I haven’t ridden regularly for a decade. I was slightly nervous about it — it’s a fixed gear bike set up for the street, with an aggressive geometry that feels best suited to someone about a decade younger than I am — but after a few blocks I found a rhythm and remembered how to slip into and out of the toe clips with a flick of my foot. By the end of the ride I felt legitimately younger, doing track stands at every stoplight, conscious that I was a little out of my element but also comfortable on the bike in ways that I’m not sure I ever was as a younger person.

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for SOW Subscribers (free or paid) only. Sign up now to read the full story and get access to all subscriber-only posts.

Sign up now