For as long as I can remember, libraries have been an important part of my life. I have fond memories of going to my local library as a kid and working on whatever project or research paper that needed doing. Flipping through the card catalog, wandering the stacks, and browsing the aisles of periodicals were all formative experiences. I enjoyed learning how to navigate a physical space that was structured around knowledge, and took great pleasure in finding the right obscure source.

I don’t get the same feeling when I browse the internet for information. Certainly, I enjoy a good digital rabbit hole as much as the next person, and my contributions to this newsletter are often the result of these wanderings. But exploring a space for a physical artifact is uniquely satisfying. It is as close to a treasure hunt as I’ve experienced.

My local library system in Cobb County, Georgia has 15 branches, employs around 200 people, and holds roughly 1 million books (220,000 unique titles). By circulation and visits, it is in the top 2% of public libraries in the United States. Over the past several months, I’ve spent some time learning about how libraries operate and what I have learned will no doubt interest this audience.

PLANNING & STRATEGY.

Libraries are described, at times pejoratively, as mere “warehouses for books.” The analogy is incomplete – it misses the broad social services and community programming the modern institutions provide – but it's not wrong. I didn’t realize just how warehousy libraries are until my recent visit to Cobb’s Automated Material Handling (AMH) room at Switzer Library.

The 15 branches in the system house a floating collection, where books have no specific home branch and move where patron demand dictates. This idea is not specific to libraries. There are many industries in which floating collections are employed, including rental cars, high end clothing, tools, bikes, and DVDs. These are all situations where patrons can rent from and return to multiple locations within a system, and inventory is distributed throughout. This PhD thesis provides a surprisingly compelling and easy to digest overview of the topic.

With a traditional collection, books have a specific home branch. If a patron visits Branch A and wants to check out a book, they can do so as long as that book is available at Branch A. If it isn’t (because another patron has checked it out), they can use a loan process to get the book from Branch B. When they are done and return the book to Branch A, it then travels back to its home (Branch B) to be checked out by someone else. This represents two stock moves within the library system.

A floating collection works quite similarly until the last step. When the book is returned to Branch A, it stays there. The return trip to Branch B (its original location) is not made, so there is only one stock move.

Floating collections can mean significant labor and transportation savings, as books no longer need to be shlepped back to a home branch after being loaned. The practice also allows collections to naturally evolve in response to the demands of the patrons that visit each branch. But the practice is somewhat controversial amongst librarians, and the labor savings do have associated costs. Shelf space in receiving branches is not unlimited, and books may need to be redistributed or culled if and when space runs out. The collections at smaller branches can suffer because popular titles naturally migrate to larger branches with more transactions. The system can also implicitly favor patrons who prefer to use library information systems (to place holds and initiate loans) over those who might prefer to browse the stacks or aren’t savvy enough to navigate the relevant app.

The general consensus seems to be that floating works best in suburban communities where demographics are similar throughout.

DISTRIBUTION & LOGISTICS.

Cobb County was able to reinforce some of the labor savings brought by their floating collection by centralizing and automating the sorting process for books moving within the system. In 2017, they installed an RFID-based bulk sorting machine at their Switzer facility, automating a process that was both physically demanding and error-prone.

The sorter, which you can view in the video above, is manufactured by bibliotheca, a leading supplier of RFID, book handling, and self-service solutions for libraries (and also the product of a ton of international mergers and acquisitions).

When scanned at the originating branch, the library information system (SirsiDynix), tells the library team whether or not an item should be placed in an interbranch tote. Three couriers pick up these totes (30-40 each morning) and bring them to the AMH room at the main branch, where the aforementioned sorting machine works its magic. The machine sorts roughly 1,300 books per day, which equates to roughly 25% of daily checkout volume. The sorting process itself takes about two hours, leaving ample time in the afternoon to courier sorted books to their appropriate check-out branches. Conceptually, this hub and spoke distribution model is a tiny version of what you might see happening at Delta Airlines or FedEx each day. Materials are brought in from far flung nodes, sorted, then sent back out to their destinations.

The Women, by Kristen Hannah, is one of the most popular books in the system right now. The floating collection has 110 physical copies, but none of them is actually sitting on a library shelf. Every copy is checked out – and there are more than 500 holds at the time of writing. Because of the large demand for the title, as soon as any single copy is returned, it is immediately routed for pickup at the next branch. Effectively, the book is held in a diffuse way by the citizens of the county. This process bears a strong resemblance to the system that Netflix used to manage popular DVDs until it closed all warehouses in April of 2023.

The roughly 5:1 ratio of holds to physical copies (known as the hold ratio) is not arbitrary. It is an important operating metric, roughly equivalent to a reorder point in a traditional warehouse. Libraries track this number across their collections and will purchase additional copies when their target hold ratio is exceeded. As you might imagine, though, a library’s ability to respond to the hold ratio signal is heavily influenced by budget considerations. Digital items (e-books and audio books) also typically have higher hold ratios (8:1 in Cobb) because digital titles are so much more expensive. A digital copy of The Women costs $60 and must be repurchased after 2 years, while a physical copy (which can be held until it falls apart) costs only $20.

MAKING & MANUFACTURING.

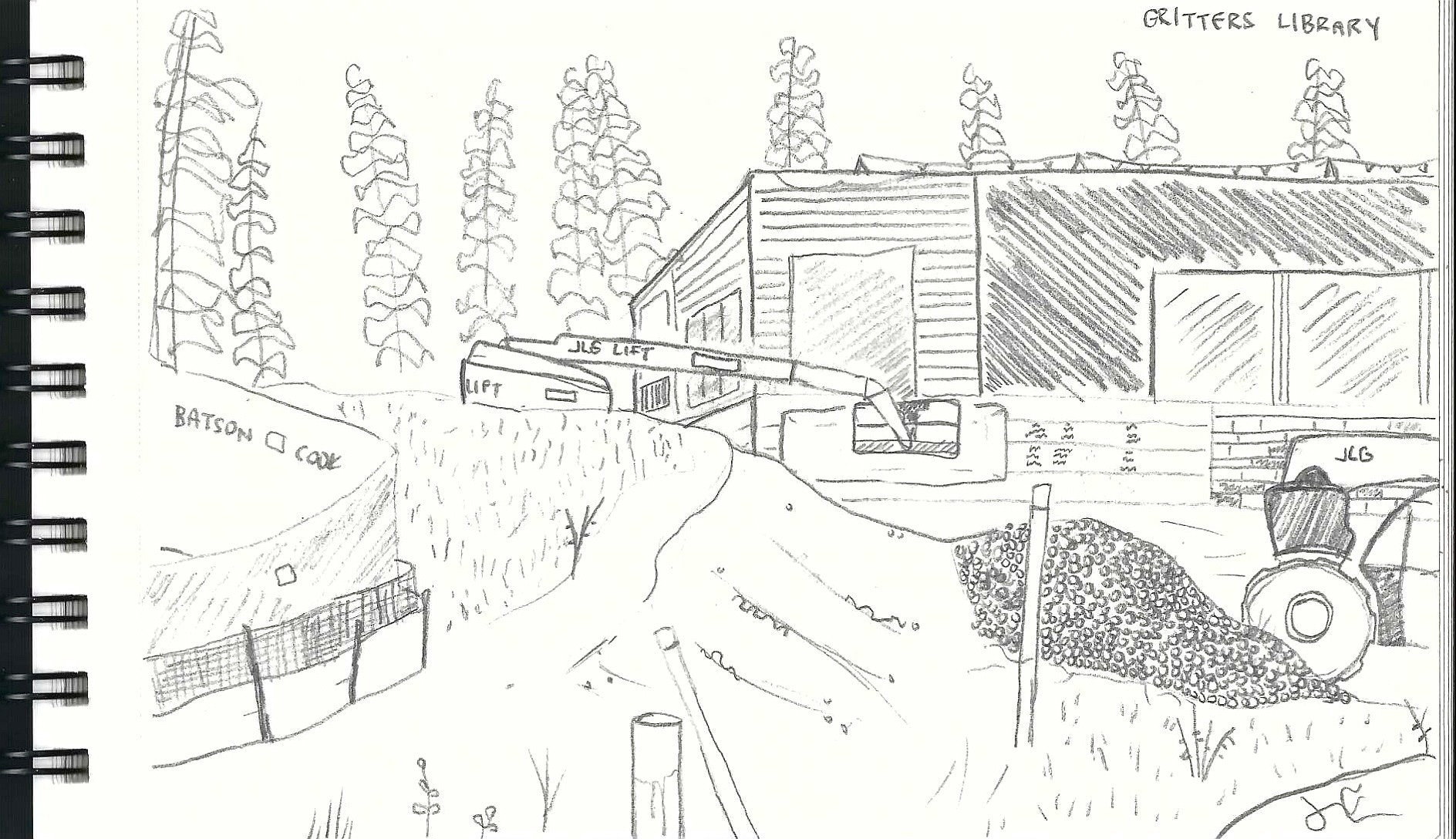

I’m participating in the Campionato Mondiale di Umari this year and you should too. If you haven’t heard about it, it's basically a friendly competition amongst infrastructure nerds to consider and document the construction sites we see all around us. Today is the last day to make submissions, which can consist of sketches, detailed notes, prose, or verse. I chose to sketch the Gritters Library (re)construction project, which is an interesting example of how challenging and time-consuming it can be to build public infrastructure, even at a relatively small scale.

When it is completed later this summer, Gritters will be the newest Cobb Library facility. The original building, which is located in the northern part of the county, opened in 1973. After more than 40 years of serving patrons, it was earmarked for a $2.6 million renovation in 2016, funded by a special sales tax ballot measure (SPLOST).

A detailed review of the facility later found significant mold and plumbing issues, and county property management determined that the approved renovation would not be sufficient to address them. A rebuild would require north of $9 million, so it fell to county leaders and the library team to close the funding gap, a process which took seven years and a healthy amount of creativity.

When the county commissioners voted to approve the final project in January of 2023, the library had become something more. They had pulled together a patchwork of funding from a variety of sources, including:

- $1.2 million from a different sales tax ballot measure (2022 SPLOST), originally earmarked for the development of a community center to serve the adjacent Shaw Park.

- $1 million from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), originally set aside to create “workforce access points” in the community that will support job search and resume development.

The new building will house not only a library, but also a community center and workforce access point. It would double in size, from 650 square meters to 1,300 square meters, to accommodate these new functions.

The Scope of Work Reading Group recently read How Big Things Get Done by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner, which chronicles the factors that make or break construction projects. One of the single biggest drivers of cost overruns and extended construction timelines is changes to the scope of work (pun intended) after shovels are in the ground. Their solution is to plan slow, then build fast. Disasters happen when you rush through the design approval process, start moving dirt, then realize that your solution is insufficient or doesn’t solve the problem.

Viewed with this lens, I think the Gritters project has been successful. Yes, it took many years to secure full funding, but this encouraged conversations between county leaders who might otherwise have missed the opportunity to work together. The old Gritters library was demolished in August of last year, and the new facility is expected to be complete in July – on time and on budget.

SCOPE CREEP.

- A delightful description of the various life cycles of a library book from a public librarian.

- While researching Netflix’s DVD distribution business, I came across this awesome Grainger ad featuring the warehouse manager for the now shuttered Anaheim facility. He discusses the three machines that enabled them to ship 1.25 million discs per week.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks also to Burr Osoinach and Helen Poyer, for touring me through the Switzer Library and patiently answering my questions.

Support your local library,

James

p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here’s what we’re doing about it.