My son turned 8 years old earlier this month. We decided to host a birthday party in our yard with a bunch of his friends from school. As if creating several hours of entertainment for a crew of rambunctious boys wasn’t stressful enough, a week of heavy rain and an ominous forecast threatened the whole event. I did not want to have that conversation with the excited birthday boy.

Fortunately, the rain subsided just as the primary entertainment was delivered: an inflatable bounce house called The Challenge, which we rented from a local vendor. The kids had a lot of fun, and I did too, eventually, after the stress subsided. Once things wrapped up, I offered to help the vendor go through the labor-intensive process of rolling and storing a 200-kilogram inflatable. I can’t say it was good for my back, but the experience made me curious about the larger industry.

PLANNING & STRATEGY.

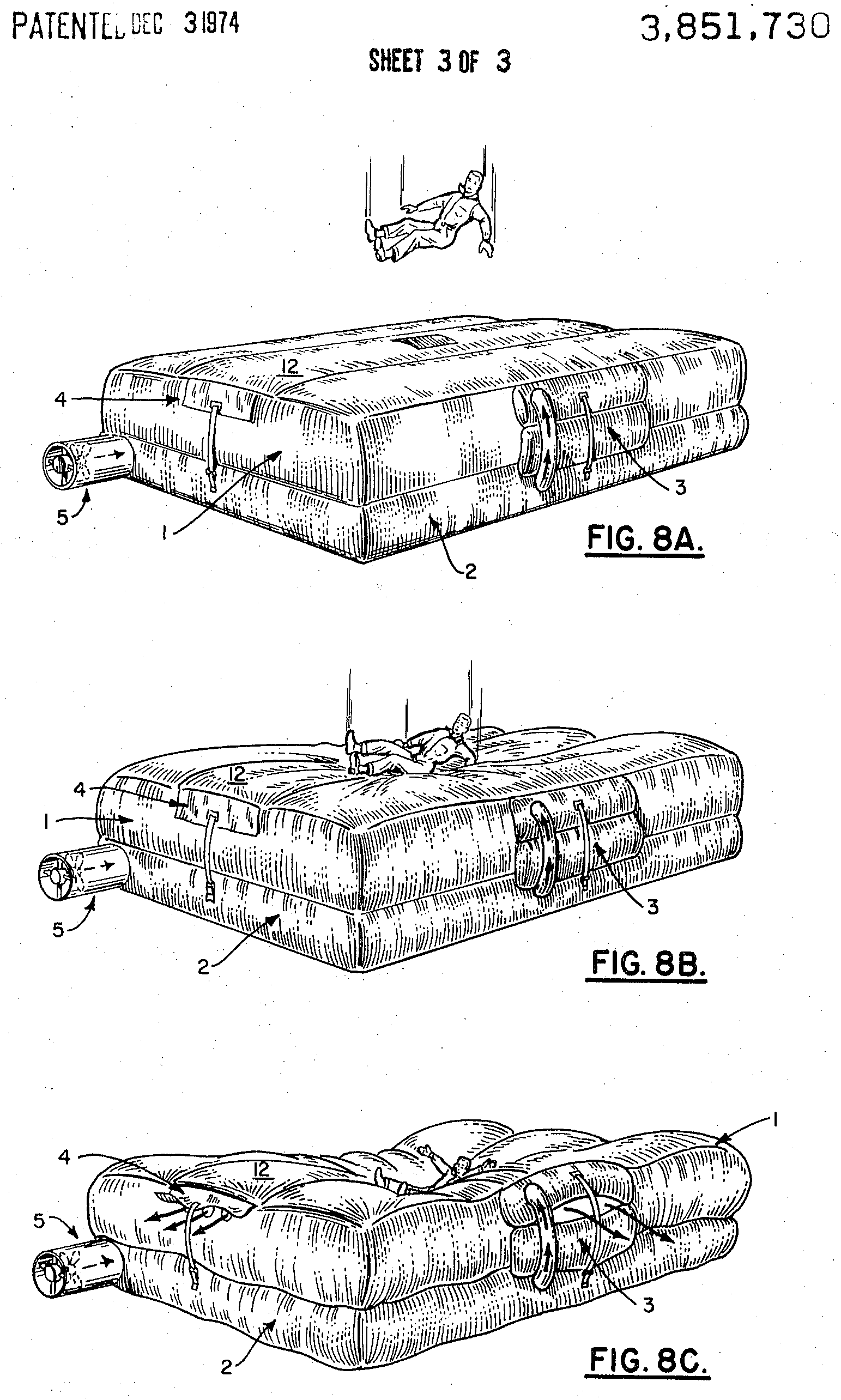

Most sources attribute the invention of the inflatable amusement to John Scurlock in the 1950s. Scurlock, who died in 2008, was an electrical engineer, physics professor, and NASA researcher who specialized in plastics. While designing inflatable covers for tennis courts, he came up with the idea for a “Space Pillow” that children could use for acrobatic play. It was little more than an air-filled bag with protective netting, but later he would use the same basic principle to create safety air cushions for fire-fighters and stunt performers. The Scurlock family still manufactures and rents amusements as Space Walk Inflatables. In 2014, they had two hundred branches and managed roughly 35,000 rentals per year. This would put them on the large end of inflatable amusement rental companies, of which there are thousands in the US.

With $20,000 and a truck, you can start renting inflatables. The low startup costs make it an attractive option for many, and there is no shortage of influencers willing to share basic business plans. But the work is arduous, with most weekends spent in a mad dash to clean and deliver amusements. (Stressed-out parents, like myself, are also no picnic.) Because there are so many small players, it is difficult to get estimates of how much money is being made in the market as a whole. Space Walk officials peg it at around a hundred million dollars annually.

MAKING & MANUFACTURING.

The Challenge was manufactured by Ninja Jump, a company based in Baldwin Park, California. Making inflatable bounce houses is a lot like making garments, albeit large plastic ones: Designers create a 3D model of the structure with a CAD program (including Sketchup), then digitally slice it into a set of flat patterns. This slicing process can involve some interesting algorithms, as the final shapes should be informed by the properties of the material and expected mechanical stresses on it. CAM software like PatternSmith then attempts to optimize pattern placement to avoid wasted material. Once set, the patterns are sent to a cutting machine like the one in this video.

Inflatables are generally made from polyvinyl chloride, which is often referred to as PVC or simply “vinyl.” There are rigid varieties of vinyl (used for, among other things, residential plumbing pipes), but when modified with the correct plasticizers as seen in this video, vinyl becomes a flexible, durable, and strong material that is perfect for bouncing. The vendor we worked with reported that with proper care, some of his inflatables have lasted more than a decade.

The cut vinyl pieces are forwarded to a seamster, who uses an industrial sewing machine to stitch the structure together. For large inflatable amusements like The Challenge, this process can take several days. There are a broad variety of ways that this design-build process takes place, but I was captivated by this detailed video overview by a manufacturer in the UK and this somewhat silly episode of Discovery’s “Some Assembly Required.”

Sewn vinyl inflatables are not air tight, like a balloon; they are designed to release air at the seams, which serve as distributed pressure relief valves. As more people bounce with varying levels of force, air is forced out, preventing burst failure. The structures stay inflated because they are attached to continuously operating air blowers. Large inflatables require blowers that put out roughly forty cubic meters of air per minute (by comparison, a standard yard leaf blower puts out about ten cubic meters per minute). This video has a pretty neat teardown of a smaller blower unit, and here an inflatables vendor shows off the blower section of his warehouse.

INSPECTION, TESTING & ANALYSIS.

Not long after my son’s party began, one of the younger kids emerged from the bounce house sobbing, eyes full of tears. Apparently, an older and larger bouncer had been a bit too exuberant and had bowled them over. This is not uncommon with bounce houses in my experience. I generally expect such minor casualties every fifteen to twenty minutes.

The safety record of inflatable amusements is a big topic of conversation. It is so important that ASTM International, the international standards organization, has a thirty-five-page set of standards that covers the design, manufacture and operation of inflatables. Standards documents are notoriously expensive, but you can view a sample of the full spec here.

Originally, the standard was only five pages long, but in a 2022 interview we published with Michael Viechweg, group leader of F24.61 Air Inflatable Amusement Devices Task Group, he recounted one factor that led to the document’s overhaul: Many North American manufacturers were upset about the influx of cheap inflatables from places like China, and they wanted something that would hold imports back. ASTM doesn’t set trade policy, but they could create a higher safety standard for all manufacturers, regardless of origin. And boy did they ever.

Had we been strictly following the operating standard at the party, our incident would not have happened as, per Section 7.5, inflatables should always have an attendant that is closely monitoring activity. Also (per Section 7.5, Table 2), participants should be grouped by size. These provisions are pretty common sense, but there is so much more.

For example, the angle of any vertex formed by adjacent components should not exceed 55 deg (5.11.1.1 (2)) to avoid head and neck entrapment. Zipper pulls for deflation should have the pull concealed by a flap or pocket (5.9.6.2) so that littles don’t mess with them. Blowers should have a non-return airflow valve (5.16.3.2) to slow deflation in the event of power failure.

Many of the most deadly inflatables accidents have been the result of high winds and improper anchoring, and ASTM F2374 − 22 covers these as well. There are two pages of equations for calculating the maximum wind forces that an inflatable can handle, another page on how to calculate current wind speeds, and three pages that describe anchoring and staking. It is an impressive document, but I don’t envy the designers that strive to meet this (necessarily high) standard.

SCOPE CREEP.

- Bob Regehr is another person credited with the creation of the inflatable amusement, using the brand name “Moon-Walk.” I came across this awesome 1960s sales pamphlet on eBay, complete with pictures and pricing. His invention is surprisingly similar to modern devices.

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now