In 2022, about 12.6% of the US population (aged 1 year or over) lived in a different house or apartment than they did a year prior. The migration rate within the United States has been steadily declining over recent decades after sitting around 20% from the end of World War II to the 1980s. While people moving within the same county consistently make up the largest share of movers, the percentage of people moving between states has been rising, increasing from 18.8% in 2021 to 19.9% in 2022.

Moving house is profoundly disorienting, throwing into disarray the entirety of your material existence, your daily routines, and your relationship to the land and built environment. It’s also one of the most significant organizational challenges people willingly undertake — a moment of intersection with the global logistics infrastructures that move things from one place to another.

Planning & Strategy.

Moving house is a very specific, personal pain, but as with all stressful life events (marriage, divorce, death) there’s an entire industry around it. Professional moving companies — previously represented by the American Moving & Storage Association, now a part of the broader American Trucking Association — are dedicated to streamlining all aspects of moving house and extracting money from the weary and frazzled. Moving is a big industry: There were 17,936 companies in the moving services industry in 2024, with over 109,062 employees.

If you’re accustomed to scrappy DIY moves, watching a moving company at work is like glimpsing a more logistically sophisticated world. If the DIY mover is a stevedore, loading lamps and houseplants one by one into a truck or station wagon, professional movers are workers at the containerized port, a model of efficiency as they stack standardized boxes into a standardized truck. The professional move is faster and more streamlined than doing it yourself, but it requires more materials, more coordination, and more infrastructure.

Part of the mover’s arsenal is the specialized box and other assorted paper products. For instance, the Dish Barrel is a double-walled cardboard container designed specifically to move dishware, enabling multiple layers of delicate kitchen items to be stacked while minimizing the risk of crushing. There are different methods for packing a Dish Barrel, both with and without cardboard dividers (which U-Haul calls cell kits). But in all cases the best practice for the Dish Barrel is to use copious sheets of newsprint before packing into a box.

A review of moving YouTube videos like those linked above reveal a curious gender binary: While organizing YouTubers (who teach viewers how to sort, label, and display items in a house) tend to be women, moving YouTubers (who teach viewers how to wrap, pack, and box items to leave a house) are more likely to be men. While the tasks are very similar, the connotations of the work — homemaking and aesthetics on the one hand, lifting and logistics on the other — keep them squarely in gendered categories.

Making & Manufacturing.

- World War II took a huge toll on British housing. The country was left with an estimated deficit of 200,000 homes due to the combined effect of damage sustained during the conflict, wartime rationing, and a shortage of building supplies like timber and brick. One solution to the shortage was Emergency Factory Made Houses (EFMs), which were designed to be built efficiently and last a decade while the supply of traditional building materials recovered. Over 150,000 EFMs — which became widely known as “prefabs” — were built between 1945 and 1951. Despite their design as temporary structures, many remained in use for decades, and an estimated 8,000 remain to this day.

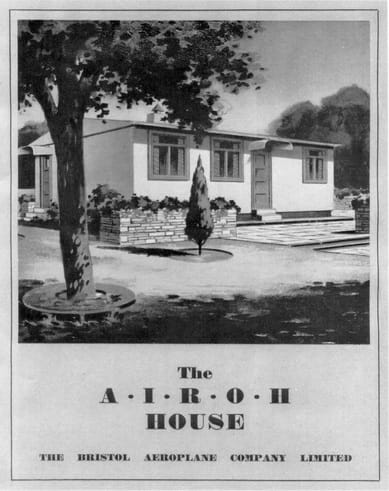

The Ministry of Works developed standards for the prefab homes, which included a minimum floor space of 59 square meters and a maximum 2.3-meter width for each component, so they could be easily transportable by road. Prefabs were typically single-storied, with two bedrooms and a standardized “central service unit” containing a kitchen and indoor bathroom. In total, there were at least 24 different designs for prefabs, which were produced by a range of companies, many of which used non-traditional building supplies or surplus war materials. For example, aircraft manufacturing facilities and expertise were used to build the Airoh prefab units, each of which utilised some of the 100,000 tons of scrap aluminum that had been salvaged from aircraft.

- The Prefab Museum has great information about the history of prefabs, including this education pack, which catalogs a range of prefab models and includes anecdotes from people who lived in them.

- This short YouTube video on prefabs, by creator Leo Jay, has great information in its own right. But the comments section is equally interesting. As is often the case with niche YouTube topics, the commenters have detailed anecdotes and stories to share that add color and context.

Maintenance, Repair & Operations.

When music producer Leroy Clampitt and his partner bought a house in Los Angeles, an additional standalone building in the backyard was a major drawcard — the perfect space for a recording studio. After six months of planning and renovation, Clampitt set up the final pieces of his studio — only to find that whenever he plugged in a new piece of gear (amps, studio monitors, microphones, synthesisers) it produced an intense digital glitchy sound that just wouldn’t go away.

This mysterious sound is the subject of a podcast episode from journalist David Farrier, and it’s a wild ride that’s worth a listen. After much investigation, and with the help of many others, Clampitt located the source of the interference: His studio was directly in the line of a cell tower hidden on top of a lawyer’s office. Moving the cell tower was a non-starter, and Clampitt couldn’t move his studio, so he went into mitigation mode and searched for a way to block offending frequencies from entering the studio. He eventually sourced a large quantity of copper sheeting and with the help of friends installed it on the outside of his studio — this “very expensive wall” acting as a sort of Faraday cage.

Scope of Work is supported by its Members and Supporters, who help keep the lights on and the writing thoughtful. Paying subscribers get full access to all issues—including this one—and help make deep, weird dives like this possible.

Distribution & Logistics.

In 2021, hundreds of people lined the streets of San Francisco to see a two-story Victorian moved 6 blocks on the back of a truck – the first time one of the iconic homes had been moved in about 50 years. Moving buildings in San Francisco isn’t unprecedented, and in fact was fairly common-place in the early twentieth century. But the practice became less tenable as the cost of building supplies dropped and the cityscape densified, adding obstacles like increased traffic and telephone lines into the mix. The city’s most well-known relocation of buildings took place in the 1970s, when twelve Victorians originally slated for destruction as part of the Western Addition redevelopment plan (a massive and notorious “urban renewal” project that displaced scores of Black and Asian American residents) were relocated in a complex process that was “like moving a herd of giant elephants.”

In New Zealand, relocating houses is much more commonplace – an estimated 3,000 houses are moved each year in a country with only 5.2 million people. There’s even a TV series about it. In one episode, a turn-of-the-century villa was transported 700 kilometers on two trucks over back-country roads, often on steep gradients with cliffs to one side. While the house was being moved in the middle of the night on the narrow Kawarau Gorge road, a refrigerated truck ignored the pilot vehicles’ instructions to stop and ended up having to back up 500 meters in the dark to enable the house to pass.

Cost is no doubt a big factor in deciding whether it makes sense to move a house. It cost the owners about the equivalent of $104,000 USD to purchase the house and move it across the South Island – around a quarter of the $400,000 USD cost just to move the San Francisco Victorian just six blocks.

Inspection & Testing.

- A fascinating piece from the Verge about the potentially-complicated business of how to move your house when its fixtures are connected to the Internet.

- In the late 2000s, U-Haul had been subject to allegations about the poor safety conditions of its trailers following dozens of sway-related accidents. CEO Joe Shoen believed the incidents could have been avoided if customers had been properly informed about the sway risk by U-Haul employees. To address the issue, Shoen gave out his personal number during a 2008 TV interview and asked customers to call him directly with their concerns, stating “he needs to earn their business.” Over a decade later, Shoen still seems to have a public cell phone number people can call him on.

Scope Creep.

- When special effects supervisor Buddy Gillespie had to work out how to make Dorothy’s house fly through a tornado in the Wizard of Oz, he landed on a deceptively simple method. A scale model of the house was dropped from the top of a soundstage and filmed, from above, in slow-motion. The floor of the soundstage was painted to resemble the Kansas sky, with dry ice vapour acting as the clouds. When the footage was put into reverse, the house appears to swirl through the air towards the viewer.

- Next week, the Frick Collection will reopen to the public after an extensive renovation of the New York mansion that houses it. Some of the craftspeople who contributed to the project – including fabric weavers, mural painters, lighting restorers and tassel makers – are profiled in this New York Times article (gift link). One massive undertaking was relocating the entire contents of the Boucher Room to the building’s second floor, where it was originally installed when the room's contents were purchased by Mr Frick for $500,000 in 1916. The process included removing and restoring every piece of the parquet floors before re-installing them in the new room.

- Daylight saving has just finished in New Zealand, and autumn (as we call it) has arrived with full force. Given the antipodean vocabulary, the mnemonic “spring forward, fall back” doesn’t really land, so a popular alternative way to remember the time change is to sing the line “put your clock back for the winter” – the opening lyric of a 1997 hit song by locally-famous rock band Shihad. The band is not likely to be familiar to our US readers, although Shihad did attempt to break into the US market in the early 00s, briefly changing their name to Pacifier because any band with a name that resembled "jihad" was unlikely to get mainstream US radio play in the post-9/11 era.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks also to Micheline for sending us links.

Love, Kelly and Anna