A peek into Montreal's mastery of snow

Before moving to Montreal in 2020, I had lived my whole life in Toronto. Toronto averages about 120 cm (47 inches) of snow a year - on the lower end for Canada, but respectable - and it always seemed to me that we were pretty good at dealing with it. Sure, we called in the army that one time during the blizzards of 1999, but what else are you supposed to do? And sure, the sidewalks in Toronto are essentially impassable for months, but where exactly is all that snow supposed to go? To me, clamoring over mounds of snow just came with the Canadian territory.

One winter in Montreal cured me of that belief. Located well to the north and east of the Great Lakes, Montreal's climate is both colder and wetter than Toronto's. Montreal averages almost 210 cm (82 inches) of snow every winter. We get less sunlight, 20% more precipitation, and have winter temperatures that are on average 4° C (7° F) colder than Toronto. And yet soon after a moderate snowfall, Montreal is bustling: sidewalks, bike paths, and streets are all cleared in a snow removal effort (le déneigement, en français) that is choreographed and masterful. To longtime residents, it can seem almost uneventful, but this winter I visited three of Montreal’s key snow removal sites to celebrate the scope and scale of the work.

In Montreal, a blizzard is a call to action. With a budget of nearly $180 million and a staff of over 3,000 workers, the city is poised and prepared to manage and remove it all. Once snow begins accumulating, a multiphase operation begins to unfold across the city’s 19 boroughs. Between roads, bike lanes, and sidewalks, the city clears over 10,000 km - roughly the distance between Montreal and Beijing.

Montreal doesn’t just push snow to the curb with plows - instead, snow is picked up by a fleet of trucks and transported up to one of 28 snow dump sites across the city. Throughout a typical winter, roughly 300,000 truckloads of snow are transported - a volume of about 12 million cubic meters.

While many US cities (and occasionally Toronto) shut down when faced with a small storm, Montreal is just getting started. Over a thousand pieces of equipment and as many operators to plow roads once 2.5 cm of snow has accumulated, and once we get 15 cm Montreal gears up into the DEFCON 1 equivalent of snow response operations. Maximum readiness. Immediate response. The first step is informing citizens when their streets will be cleared. In dense, downtown neighborhoods, most people park on the street and their cars need to move. No parking signs get installed block by block and notifications go out through the city-maintained snow removal app, InfoNeige (equivalent to InfoSnow in English). Municipal lots are opened up with free parking, and as one final warning, tow trucks blare a siren before hauling away any outstanding vehicles.

Once personal vehicles are out of the way, scores of snowblowers and trucks descend upon the city, carving up snowbanks and carting them away. They march through the city in platoons, with a single blower trailed by a long line of empty trucks. After the first truck is filled, the next one in line moves up in a seemingly endless parade.

My guide through the blustery world of snow removal was Philippe Sabourin, Montreal’s spokesperson for all things infrastructure. Philippe graciously led me to three key sites where snow trucks carry off their icy cargo. Just as the city is prepared to deal with the vast truckloads of snow, Philippe is prepared to talk about it. Between our conversations, he peeled off to update newscasters on the removal progress.

The first wave of snow trucks makes their way to the city’s 16 sewer chutes, where loads of snow are plunged into the wastewater sewers through grates the size of a garden shed. The sewers below flow with hot water from the showers of Montreal’s two million residents, our small contribution to melting all of this snow.

These chutes process 25% of the city’s snow, and the meltwater flows through the sewers to the water treatment plant in East Montreal. It’s a clever scheme, saving gas by limiting the transportation distance and ensuring that salt and other impurities are filtered from the water before it is released into the St. Lawrence River.

At the snow chutes, trucks back up to the mouth of the grates to dump snow down into the depths. Excavators are stationed nearby, and workers use them to crush any large clumps of snow through the holes and down the chute. Before another truck can pull up, another worker inspects the chute for obstructions. When temperatures drop, icy snow may not melt readily and can build up in the sewer, delaying operations. This step is crucial: while the chute I visited was working well, we soon drove past another that was obstructed; a long line of trucks was left waiting for it to be cleared.

The other 75% of the snow is stockpiled in landscape dumps across the island of Montreal. I visited the Angrignon snow dump in a western industrial district, a fenced-off lot with an area roughly equal to 18 football fields. The perimeter of the site was lined with a mountain of snow that towered over the trucks queuing to tip their cargo, but my guide wasn’t as impressed as I was. This was still early in the season, Philippe told me, and the mountain would soon climb to thirty meters and fill in the entire lot.

This ever-growing pile of snow is built up by an oversized snowblower, with blades twice as tall as the machines on city streets. Operations are carefully choreographed: when a truck enters the lot, the driver finds their place in the queue. The trucks are separated by size to ensure the snowblowers tackle equally sized piles of snow, keeping a consistent flow of material to build up the towering snow pile evenly.

The trucks get into formation, lined up side by side along the base of the mountain. They tip their loads in front of the blower so it can continue plodding along uninterrupted, shooting a ribbon of snow far into the air. While Angrignon boasts the biggest blower, the same process is repeated at 11 sites across the island of Montreal.

The final site we visited was the crown jewel of Montreal’s snow storage strategy: the Francon quarry. In decades past, it provided the limestone that built Montreal’s posh downtown districts. And since its retirement, it has become the city’s largest snow dump.

As we descended the gravel road, I was stunned that this massive quarry - 2 km long, up to 580 meters wide, and 80 meters deep - is hidden in plain sight. The surrounding commercial streets are home to grocery stores, dollar stores, and low-slung industrial buildings - the patrons of which seem totally unaware of the busy hive of activity around the corner.

Standing at its bottom, the quarry’s scale defies comprehension, Philippe said even after years, visiting the quarry fills him with a sense of awe - like stepping into Jurassic Park. At the top of its sheer limestone cliffs, trucks back up to the edge and send snow cascading down to collect in ever-broadening pyramids, eventually amassing 4.8 million cubic meters. It can take until the following autumn for the compacted snow to melt and get pumped out into the wastewater system. Some years, it doesn’t entirely, leaving a glacier at the bottom of the quarry.

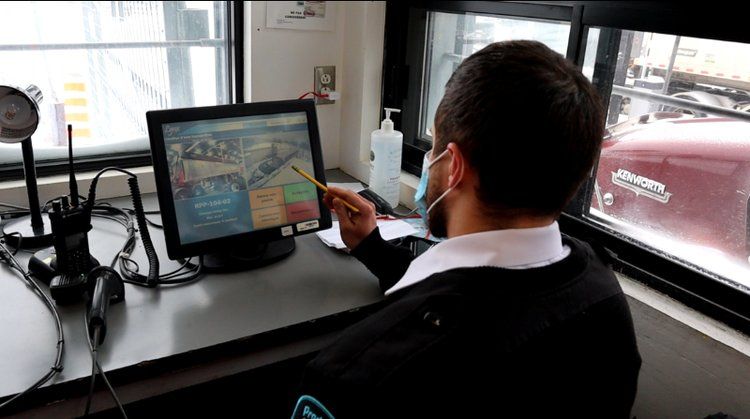

Quarry operations peak overnight, with 300 trucks passing through each of the five intake stations every hour. At the top of the quarry, intake gives a window into how all of the city’s workers and equipment are managed. As each truck pulls up to the station, an agent verifies their ID to ensure the load has been contracted by the city and checks the overhead camera to ensure the driver has brought a full load. With millions of dollars in contracts awarded, this is a safeguard against contractors cutting corners.

Standing at the top of the quarry with trucks trundling in I was grateful for this glimpse into the network - the coordination is astounding. From this vantage point, snow operations feel like the city’s circulatory system, diligently clearing all of its arteries. The nervous system of the operation is the integrated digital network linking the GPS from each truck, to city workers, planners, and citizens. And just as our bodies’ systems work together to keep us healthy, the layered systems of Montreal’s snow operations work together to keep the city living and vibrant through the coldest season.

Living in Toronto, a snowstorm was treated as a shocking anomaly. Plows often cover sidewalks over for weeks, forcing pedestrians to walk into oncoming traffic and barring neighborhoods from people with mobility issues. But in Montreal, clear sidewalks ensure strollers and wheelchairs can keep rolling, and 75% of the bike lane network is cleared all winter. This means clear sightlines to oncoming traffic; it means bike rides with friends; it means more equitable access to personal mobility. With few barriers to travel, people across the city pour out into parks all winter to ski, sled, skate, or just bask in the open space. I was personally pretty intimidated to move to a city known for intense and snowy winters - but I’ve been blown away by the mountains of snow that get blown away before my eyes.

Thank you to Philippe Sabourin for sharing his enthusiasm and knowledge, and to all of the other municipal workers who took the time to talk with me. Thanks also to Scope of Work's Members Slack for cheering along from the digital sidelines.

If you need more Montreal snow removal in your life, see: