Here’s a surprisingly compelling corner of the engineered world: Nineteenth-century apple parers.

Sometimes my kids request that an apple be peeled, and if time and energy allows then I’ll reach for a general-purpose kitchen tool (a vegetable peeler, a paring knife) and oblige them. This happens relatively infrequently. Even if I peeled every apple that we ate, that would still only amount to a few peelings per day.

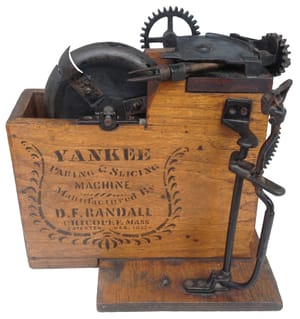

Apple peeling was apparently much more common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and from the ubiquity of the task arose countless solutions. I like to think of them as akin to a field of wildflowers, each attempting to advance its own strategy to a common problem. They – the apple parers – are described in a broad and intricate taxonomy in Don Thornton’s 1997 book, Apple Parers. The book is over two hundred pages long, and contains over five hundred and fifty photos and two hundred and fifteen patent drawings. It describes apple parers – manually-operated machines which quickly remove an apple’s skin and, in some cases, also core and slice them – as meaningful pieces of infrastructure to early American life, and as a category of tool for which “the competition was intense.”

Apple parers utilized quite varied design strategies over the years. Broadly speaking they can be divided up into lathes, turntables, returns, arcs, commercials, and primitives – though these terms overlap quite a bit, and you might think of them more as attributes than as distinct categories. Regardless, the design language on display in Apple Parers – and in the Virtual Apple Parer Museum – is nuanced, evolved, and colloquial. There are also copious references to “Yankee ingenuity,” a term that I find a little too earnest, but which I’m sure conveys something true about the entrepreneurial energy devoted to apple-peeling machines at the time.

And anyway, it’s delightful to read essays on specific antique parers which note the author's “weak knees” when first seeing the parer in question. Perhaps more striking are the words of appreciation for the community around apple parers; it’s evident that the International Society of Apple Parer Enthusiasts (nicknamed APES) provided many of these people with genuine, long-lasting social warmth. The foreword of Apple Parers spends much time describing these relationships, noting also that the writer shared an enthusiasm for apple parers with colleagues while working at Lockheed in the 1970s and 1980s. As Ben Rich describes it in Skunk Works, the Lockheed engineering culture at that time was confident, hardworking, and fast-moving; perhaps the iron gears of apple parers contained a relatable flavor of nineteenth-century techno-optimism.

Apple parers seem to show that for any particular problem – how to pare an apple, how to join two pieces of metal, how to produce baseload power to the electrical grid – there should be a nearly endless number of solutions. It is this fact that excites me most about browsing a hardware store or industrial supply catalog. If a tool comes in many varieties, that’s proof of a problem that many people have tried to solve before me. Selecting a tool, then, is an opportunity to see my problem from someone else’s vantage point.

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now