A brief history of just-in-time manufacture

The pandemic has brought not one crisis, but many. Supply disruptions have meant that products from paper to paint have had prices rise and deliveries delayed. The causes are complex: Global shutdowns constrained supply; consumption patterns shifted unexpectedly; disruptions in distribution kept products from reaching store shelves.

Is this just a temporary glitch? Or is it a symptom of some deeper, more systemic flaw in production?1 After all, this crisis has demonstrated that there is little slack in the system. But the supply chain wasn’t always so lean. In the years leading up to the new millennium, companies in the United States increasingly turned toward a new mode of production, and to the practices of outsourcing it made possible. In 1997, for example, Steve Jobs explained that, now, “every single product…is going to be build-to-order in our factory.” No longer would so many of Apple’s products be prepared in advance. Instead, they would be made just in time. And soon enough, this was the default position for most (if not all) technology companies.

The Way

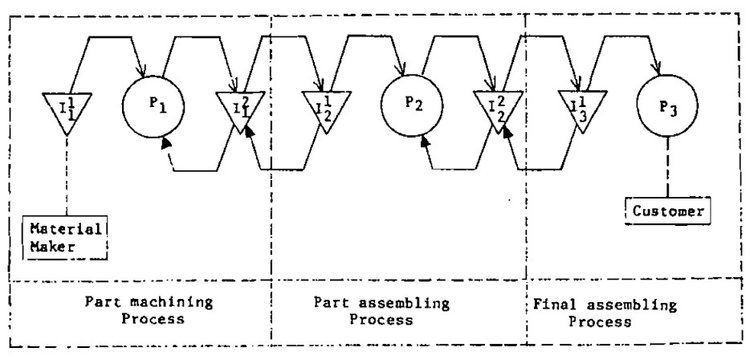

While what has come to be known as the Toyota Production System began in the immediate aftermath of World War II, it first came to attention in the United States during the late 1970s.2 Even then, Toyota didn’t present the system more broadly until 1992, when they published a 44-page pamphlet titled The Toyota Production System: Leaner Manufacturing for a Greener Planet.3 While what we have come to know as just-in-time production is not the only element of the Toyota Way, it is certainly a central feature. The basic idea, Toyota explained, is to arrange “all the processes in the production sequence in a single, smooth flow.” This is accomplished by having each process deliver output for a subsequent process only "when it needs them.” Additional supply, in other words, is made "only to replace items" that have already been consumed. But the system didn’t stop when a car rolled out of the factory. "The final process in the chain," Toyota explained, "is the dealer who sells cars to customers." By directly connecting consumption to the factory, the system demanded that assembly plants "make vehicles only in response to actual dealer orders," with suppliers making parts "only in the kinds and quantities needed to replace items" the vehicle plants have used, shipped, and sold.

This is just-in-time production: "making only what is needed, only when it is needed, and only in the amount that is needed." The result, Toyota claimed, was not only a radical reduction in waste, but in costs associated with financing and storing inventory. It should be obvious, of course, that this system required some underlying structural changes. The first was linking the pace of work to the pace of sales, and a reliable means of distribution between the factory and the retailer. The second was a network of suppliers and partners who were also operating "just-in-time." While the first requirement is explicit, the second is not. Indeed, Toyota goes to great lengths to argue that it isn’t a requirement at all. But just-in-time is contagious, and when a company adopts it, supply contracts become smaller and shorter, demanding a responsiveness that is difficult to achieve without suppliers operating in the same way. After all, just-in-time production affords the flexibility to make frequent changes throughout production cycles, or to correct “defective” runs – something that is challenging with large, static inventories. The risk of holding parts that may no longer be needed by your largest customers means most suppliers soon came to adopt at least some elements of the system.

This approach may have begun in Japan, but it didn’t stay there. Buoyed by post-war investments in infrastructure, Japan’s “economic miracle” made it the world’s second largest economy, and its global expansion drew attention. "The Japanese have taken a large share of the North American market from North American manufacturers," wrote J.P. Kelleher, the President of the American Production and Inventory Control Society. Indeed, Kelleher joked that "conducting tours of Japanese manufactures” had become something of “a growth industry."

The 1983 publication of Robert Hall’s Zero Inventories represented one of the more significant efforts to introduce just-in-time principles to North American business. Toyota had demonstrated how to have “all processes produce the necessary parts at the necessary time” with “only the minimum stock necessary to hold the processes together.”4 The name that Hall gave his system–stockless production–should make clear how completely he embraced that goal. While "instantaneous conversion of raw materials to finished products" was, Hall lamented, "not literally possible," what ought to be was the ability to "produce one unit of whatever is wanted by the customer at any time." Here there is no waste—no waste of labor, material, or equipment. Everything that goes to customers is precisely what they want. While many were skeptical, there is no denying that stockless production has become its own growth industry. The economic efficiencies it promised have led to its adoption across a wide variety of industries–and consumers have (generally) responded with increased satisfaction.

Shuffling Suppliers

But there are some observations in Hall's writing that might, in retrospect, have given one pause. Many smaller companies, Hall noted, expressed concern that stockless production was "primarily a program to deliver materials from suppliers to industrial customers in small quantities and at frequent intervals" – and, as such, "to shift the burden of carrying their inventory" without compensation. While he argues that any shift in inventory would only be temporary, critics noted that this was only true if the supplier also moved to the same mode of production, and in Japan most suppliers followed that trend.

In part to address this concern, Hall considered the history of supply networks in Japan, noting how fundamentally different it was from the network that had developed in the United States. Here he makes a distinction between "type I" and "type II" suppliers. Type II suppliers, he explained, have "skills not possessed by the customer and not easily developed by them"; they are experts in their respective areas, and as such they work with industrial customers to solve problems. They are, in other words, partners in areas the customer does not specialize in. Most American suppliers, Hall suggested, were type II suppliers.

Most Japanese suppliers, on the other hand, had begun as type I suppliers: They were distinguished primarily by their capability to deliver materials at lower cost. This was either because they had lower labor costs, or used more specialized equipment, spreading its cost across multiple customers. In Japan these suppliers had been inextricably tied to the development of large firms like Toyota, and those firms often directly loaned money for their creation while maintaining exclusive or preferential arrangements. These were subcontractors, in other words. This was not a network built on partnerships between equals, but with subordinates in a supplier family.

There is a common perception that mass production is primarily about producing things at scale. But this has always been an incidental effect of the underlying system. Mass production is sometimes called continuous production, and by every measure this is a more accurate label. It is a way for assembling one part after another, performing one process after another, with each stage of production proceeding in sequential operation. It is about flow, and the control of flow. Indeed, what struck observers of the Toyota system was not that it never stopped moving—but that it stopped moving all the time. “Jidoka” meant that the assembly lines were “equipped with stop buttons at each station,” and workers on the line were told to push the button “anytime they were unable to finish a task.”5 Usually this indicated that the line’s operation might need to be revised. But it also demonstrated a responsiveness to the individual elements of the system.6 While the economics of setting up an assembly line may favor a certain scale of production, its flow has always been the primary variable of interest. It’s just that, prior to just-in-time production, only certain segments of that flow could be reliably accounted for.

This was something that companies in the US struggled with. Apple–which radically reconfigured its mode of production at the end of the 1990s–offers a helpful example. “In the past,” Vic Rinkel, VP of Worldwide Materials, noted, the company had to “guess what that demand was going to be, and a lot of times we’d get it right and a lot of times we’d get it wrong.” But as they embraced more elements of just-in-time production their factory was able to reconfigure flow, and as a consequence Apple was able to keep less finished inventory. Heidi Hedlund, Apple’s SVP of operations at that time, couched this in terms of consumer value. “Build to order,” she explained, “allows us to pass [cost savings] on to the customer, without burdening [them] by the fact that we’ve had to hold inventory on products that the customer doesn’t want.” By switching to standard components, Apple followed the lead of competitors like Dell in shifting away from what were, essentially, Hall’s “type II” suppliers. They left behind technology partners and internal manufacturing for a broader supplier network with a lower labor cost.

Inventory, Apple’s Tim Cook has been quoted as saying, is not only evil, but “fundamentally evil.” Under his direction Apple’s factories in Singapore, Cork, and Sacramento were sold off; everything but the design of the computers was outsourced to Chinese firms. As the rest of the industry followed suit, inventory levels went down, production scale went up, and labor costs increasingly shifted to outside firms. In developing a leaner, more continuous approach to production—by more finely controlling the timing of flow and moving to what Hall had called “type 1” suppliers—US firms were effectively able to distribute their work across space, with all of the troubling implications that outsourcing entailed.

Always Just in Time

The transition to just-in-time is often singled out as a critical point of disjuncture in the history of making. But the ideas behind it are not, themselves, particularly new. The history of manufacture has never been a linear march. There have always been batch processes that kept materials available, just as there have always been those who "made to order” and sold from samples. Just-in-time formalized a pre-existing (if more partial) way of doing things. Inventory didn’t go away–it was just better distributed, leveled out to raw(er) ingredients coming together at a more appropriate time.

If it offered anything different, it was in the orientation of supply—from “supplying” parts to subsequent processes to “withdrawing” them from preceding ones. This does make shortages feel more acute – but it doesn’t make them more likely. For Toyota, “no process [was] allowed to produce extra amount and have surplus stock between the processes,” but rarely has this mandate been taken up completely by another firm.7

In fact, we have always made many—in not most—things “just in time.” And for good reason. Not only is the ability to mass produce goods speculatively an incredibly recent possibility, it has rarely made sense to have large reserves of excess supply. Just as there has never been much of anything at the “back of the store,” it has almost never been the case that a merchant went to market with the hope of maintaining excess inventory, or keeping a warehouse overly full. When they did, it was usually the result of exceptional circumstances, industry agreements, or government intervention. In those terms, “just in time” is not very different from the patterns of supply that came before: Governments stockpile; manufacturers don’t. And while there are exceptions—indeed, my own work on the Bell System and the Western Electric Company provides exactly such an exception—these say little about the historical image of supply. Between 1997 and 2007 Apple went from thirty days of inventory to less than two. The pandemic hasn’t given us thirty days of disruption, but months–now years–on end. Twenty-eight more days of inventory just isn’t enough to make a difference, not with months of lockdown and disruption. It wouldn’t have kept enough paper towels on shelves, or made it any easier to buy a PlayStation 5.

So why has this supply crisis felt so significant? Part of it is the global scale of the pandemic. Previous disruptions were more partial—geographically localized and temporally constrained–but this crisis has no expiration date. And with predictions about the future prevalence of pandemics, and the increasing effects of global climate change, it probably never will.

The other factor is the distance between the stops on the supply chain. As labor has shifted to increasingly diffuse peripheries, the movement of materials has become more complicated. There are more chokepoints—more opportunities for the circumstances of geography to intrude on the flat world of the supply chain. Every border crossing, every port, provides an opportunity for friction, and the infrastructures for all sorts of specialized manufacturing are now worlds away from each other. And it is this geographic distribution–not just-in-time manufacturing–that is the biggest cause of pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions. It is, in other words, an inevitable consequence of global supply chains.

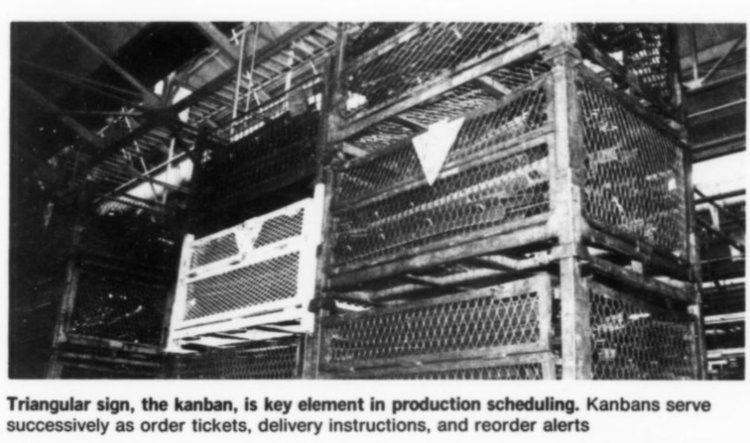

Equally important is how just-in-time was adapted to the United States. For many firms, the adoption of lean production techniques in the 1980s and 90s corresponded with increasing computerization of their production process – and the adoption of Material Resource Planning systems in particular. But when software that had primarily been intended to plan was increasingly used to predict, the ideas that had informed Toyota’s work—a responsiveness to the material facts of Kanban cards embedded in the actual machinery of production—became increasingly abstract.8 They were no longer just just-in-time. They were the imagination of what might-just-be. And when these predictions have failed, and there is nothing to pull from in reserve, the effects have proven catastrophic. When faced with unpredictable circumstances, the industry response has been to shore up models, double down on a future of artificially-intelligent planning systems. Of course, this all assumes a future that we could actually plan for.

Critics have argued that, instead of just-in-time, we should return to “just in case.” But the truth is there is nothing to return to; for nearly all of the consumer economy, “just in case” never really existed in the first place. Perhaps a more productive conversation would be to ask what it is we want to find in the back of the store–cases of what? After all, one of the greatest limitations isn’t the availability of finished goods, or even of raw materials, but the tools of that assembly: manufacturing equipment and machinery. An “inventory of assembly” would redirect us to the specialized infrastructure of production, the geographies it has come to occupy, and the patterns and practices it requires.9 The most certain way to make sure one has things, after all, is to have the things that make them.

Notes

-

See, for example, Peter S. Goodman and Niraj Chokshi, “How the World Ran Out of Everything,” New York Times, June 1 2021; Josh Toussaint-Strauss, Ali Assaf, Joseph Pierce, Nick Hildred, Ryan Baxter, Paul Boyd, “Just in time: why we keep running out of everything,” The Guardian, January 27 2022. ↩

-

Where it was initially described as the “Ohno” system, after Taiichi Ohno, or the “Kanban” system, for the cards that “serve successively as order tickets, delivery instructions, and reorder alerts.” ↩

-

Quoting the revised version unless otherwise noted, see “The Toyota Production System: Leaner Manufacturing for a Greener Planet” (Japan: Toyota Motor Corporation, 1998). ↩

-

Sugimori, Y., K. Kusunoki, F. Cho, and S. Uchikawa, “Toyota Production System and Kanban System Materialization of Just-in-Time and Respect-for-Human System,” International Journal of Production Research 15, no. 6 (1977): 553–564. ↩

-

“Toyota's 'famous Ohno System,’" American Machinist 121, no. 7 (1977). More accurately, workers would pull the hanging “Andon” cord to signal a stoppage or–in some cases–the system would automatically stop. ↩

-

This explains why the system doesn’t prevent variation. Branching flows, for example, are certainly possible. ↩

-

Sugimori, Y., K. Kusunoki, F. Cho, and S. Uchikawa, “Toyota Production System and Kanban System Materialization of Just-in-Time and Respect-for-Human System,” International Journal of Production Research 15, no. 6 (1977): 553–564. ↩

-

MRP approaches are future oriented, they model operations to allow for appropriate resource allocation for future processes. JIT systems don’t plan like this, they respond. MRP in other words, is a push system, it pushes supply just as JIT pulls it. It is the difference between running out of something unexpectedly, and knowing you have to wait before you can move to the next step. For more on the early differences between Toyota’s system and the American MRP II systems, see, for example, Brian Maskell, Just In Time: Implementing the New Strategy (Carol Stream, IL: Hitchcock Publishing, 1989) ↩

-

See, for example, Kim Moody, “The Supply Chain Disruption Arrives ‘Just in Time,’” Labor Notes, December 6, 2021. ↩