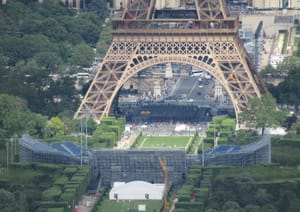

When the Olympics were held in Paris this August, only one permanent sporting venue was built specifically for the occasion. In addition, organizers utilized existing facilities and built seven temporary venues in iconic locations like the Palace of Versailles and Place de la Concorde. This approach reflects a wider change in Olympics strategy, which aims to attract host cities that may otherwise be scared away by the risk of budget blowouts, white elephant venues, or significant debt. It’s not every day that a city, even one the size of Paris, needs a permanent swimming venue with room for tens of thousands spectators. So, instead of leaving the city saddled with new venues with high maintenance costs and limited ongoing utility, crews will remove and dismantle hundreds of thousands of temporary seats and scads of scaffolding by the end of October, leaving little permanent trace.

The temporary venues built at the Paris Games, along with recent announcements about the LA 2028 Games – for which a 34,000 capacity temporary swimming venue will be constructed inside SoFi stadium – got us thinking about temporary structures that are erected to serve a particular purpose for a short time. Of course, all human-built structures are temporary in the longer scheme of things. While there are famous examples of thousands-year old architecture, the average lifespan of a house in the USA from construction to demolition is a much more modest 50-60 years. A difference is that temporary structures built for a fixed purpose and timespan are explicit about their fleeting nature.

Temporary structures are planned and executed with a different set of parameters and considerations than those designed to last for decades or more. They often require complex logistics and operations behind the scenes, and their implementation requires the balancing of potentially at-odds factors like cost-effectiveness, safety and sustainability. In this edition of Scope of Work, we look at what it takes to build something for a good time, not a long time.

PLANNING & STRATEGY.

From earthquake shacks to circus tents, temporary structures serve a broad gamut of purposes both physically and conceptually. We hypothesize that temporary structures generally fit into one of three broad categories:

- Shelter

- Emergency

- Entertainment

Shelter is the most self-evident. For millennia, people have set up temporary dwelling structures to protect themselves from the weather, bugs and animals, and other people. Nomadic communities often set up seasonal dwellings, like yurts and tents, which can then be packed for transport to new locations. Hikers may bring a tent, tarp, or bivvy with them as a sleeping place in the wilderness. The temporary shelter addresses the most basic of needs — to be warm, to be dry, to have a little privacy, to make a place into a home.

Emergency structures are built to address an immediate need, often in a time of crisis. Field hospitals, Covid-19 vaccination centers, and FEMA cabins all fall into this category. While the incredible speed at which these structures are often assembled create the impression of spontaneity, emergency structures tend to be supported by extensive planning, logistics systems, and standards that ensure they are ready to be deployed with little to no warning.

Entertainment includes temporary structures and infrastructure for arts, cultural, and sporting activities. This includes everything from Coachella, to the Ringling Brothers, to the huge grandstands lining streets for the Monaco Grand Prix. Cities and states often have a hand in these structures, as entertainment is seen as having positive social value, bringing in tourists or investors and activating an otherwise underutilized space. Today’s temporary temples of entertainment follow in the tradition of the Greek theater or the Renaissance carnival, offering a space for a population to come and find catharsis, blow off steam, or escape the strictures of everyday life. That is, they help maintain social order by creating a space for order to be temporarily disrupted.

Across all three categories (and in the overlaps between them), temporary structures create a kind of temporary community. People come together in short-term spaces to celebrate, commiserate, or fix problems. They also come together to devise and build the temporary structures themselves — a fleeting community of labor and logistics. The world of the temporary structure lets us catch a glimpse of what another mode of living, or another mode of social organization, might look like.

MAKING & MANUFACTURING.

- Over their five-decade collaboration, artists Christo (1935–2020) and Jeanne-Claude (1935-2009) planned and made enormous-scale fabric installations that interacted with the natural and built environments. The process for planning, producing and installing these temporary works was arduous, and it took years – sometimes decades – to take a project from initial idea to reality.

The last large-scale work installed before Christo’s death was The Floating Piers in Lake Iseo, Italy: three kilometers of yellow floating paths connecting the town’s streets to a nearby island. Christo and Jeanne-Claude first came up with the idea in 1970, but planning proper didn’t start until 2014, after Jeanne-Claude’s death. On undertaking the project, Christo said “I’m going to be 80 years old, I’d like to do something very hard.” When it finally opened in 2016, the work was visited by over 1.2 million people during its sixteen public open days. The whole process is documented in the 2018 film “Walking on Water.”

The Floating Piers were built from 200,000 high density polyethylene cubes, produced in four factories in northern Italy (where possible, Chriso and Jeanne-Claude used local vendors for their projects). The cubes were fastened together into 100-meter sections by workers in on-shore workshops, a process that took months to complete. When the sections were installed into their final configuration, divers fastened them to 160 anchors, each weighing five tons. Rolls of felt were helicoptered to the piers and unfurled as a base layer across the entire structure before being covered in 90,000 square meters of saffron fabric. Over six hundred workers were involved in the installation of the piers. - Plaster of Paris (powdered gypsum) was used extensively in the construction of temporary buildings for international exhibitions and world’s fairs in the late 1800s and early 1900s, many of which had elaborate facades that emulated marble or stone. Plaster was mixed with water and other additions like cement, glycerin, and dextrin to form a material called staff, which could be cast in large molds, often strengthened with jute or burlap. Staff was used heavily for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago and the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco, both of which featured temporary buildings erected on sprawling sites.

MAINTENANCE, REPAIR & OPERATIONS.

- Sometimes, structures that were designed and built to be temporary endear themselves to the community and are made permanent – either by preserving the original structures or by rebuilding them in more sturdy materials. Civic icons like the London Eye and the Eiffel Tower are both previously-temporary structures, as are a whole set of more modest edifices like the parklets and outdoor seating areas established in the early days of Covid-19. Temporary structures built in exceptional circumstances – be it a World’s Fair or a pandemic – can let people see possibilities for their cities that concept sketches alone can’t offer.

- The Palace of Fine Arts is the only architectural remnant from the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco — a temporary structure turned permanent. Designed by Bernard Maybeck and originally built from staff and wood, the Palace exaggerates forms found in Roman architecture, with a 46-meter-high rotunda forming its central feature. The Palace was a hit with many locals, and in 1925 city officials voted to keep the buildings permanently. By the late 1950s the structures had fallen into significant disrepair. The cost to rebuild the Palace in permanent materials (poured-in-place concrete with steel reinforcement) was significant, and some officials considered it too expensive for the city. The project eventually went to residents for a vote, which was successful, and the city was able to cobble together the $7.7 million ($69.3 million US in today’s money) needed for the restoration.

DISTRIBUTION & LOGISTICS.

- Originally developed to enable the immediate treatment of injured troops during war, field hospitals are also deployed to treat civilians during conflict, sudden onset disasters, and public health crises. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) developed its Modular Field Hospital close to twenty years ago, with its most recent deployment being to Chad in 2023 to treat victims of the war in Sudan. MSF has three fully prepared Modular Field Hospitals ready to go at all times – two in France and one in Belgium. They include physical infrastructure like tents, pre-packed kits with all the supplies needed for a range of treatment areas, and other items like pens and paper. The logistics of getting the Modular Field Hospital set up are complex, with factors including transporting heavy gear to the site (often during times when charter planes are in high demand), having access to water, and language barriers. Despite this, the MSF field hospital in Chad was fully functional nineteen days after it was ordered, with a 170-bed capacity.

- The World Health Organization issues standards and taxonomies for Emergency Medical Teams deployed globally, with the most recent version issued in 2021. The guidance includes technical standards for clinical care and operational support and aims to ensure that teams “speak the same language” about the capabilities they can provide. Prior to the first edition in 2013, the organizations deploying field hospitals had different terminologies and approaches, making it difficult for governments to understand what was being offered and make decisions accordingly.

- An overview of field hospitals around the world that were deployed during the initial stages of the Covid-19 pandemic.

INSPECTION, TESTING & REGULATION.

- The permitting requirements for temporary structures varies from place to place. In New Zealand, where Anna lives, a building consent is not required for tents, stalls, marquees and booths under 100 square meters in size, and in place for no longer than a month.

- Most US states and territories adopt the building and fire codes issued every three years by the International Codes Council. The 2024 building code includes a number of updates to provisions for temporary buildings, including extending the maximum time they can stay up from 180 days to a year. This change reflects that many of the temporary facilities required during Covid-19, like field hospitals and testing sites, needed to be functional for longer than the previous time limit allowed. Changes to the code also include reductions to some load limits (including for ice, snow and wind), which previously had been the same for temporary buildings as permanent structures.

SCOPE CREEP.

- Architect Shigeru Ban’s practice spans both high-end commissions and temporary buildings built in the wake of disaster, often built from cardboard tubes – a method he first developed in 1986. While many of the materials and techniques stay the same across different projects, a large part of Ban’s practice is building relationships on the ground and understanding the specific needs of communities. This video shows a timelapse of the construction of the “Cardboard Cathedral” built in Christchurch, New Zealand after the 2011 earthquake.

- A timelapse video of two pools being installed in Indianapolis’ Lucas Oil stadium for the 2024 US Olympic swimming team trials, and a detailed breakdown of the decision-making process and logistics that went into making it happen.

- For five days a year, Worthy Farm in the Southwest of England becomes home to over 200,000 people for the Glastonbury Festival – making it the 28th biggest town/city in the UK for a week. While the frame of the festival’s iconic Pyramid Stage is a permanent fixture, a lot of temporary infrastructure is needed to support that many people, including mobile networks, additional stages and toilets.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible.

Love, Anna and Kelly

p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here’s what we’re doing about it.