Like a lot of you, I’m sure, I’ve been feeling kind of weird about the things I buy. I’ve been thinking about where they come from, and how I feel about that, and if I feel bad about it, how I’d like it to be different, and how I’d approach changing it. If you’ve been thinking about these things as well, stick with me. Maybe we’ll get somewhere together.

I have this bit I do sometimes about the word “mature.” Sometimes we act like “mature” corresponds with a certain set of traits, which we associate with adulthood. If pressed, we’ll acknowledge that this set of traits is somewhat arbitrary. In the United States in the year twenty twenty-five, this set of traits might include things like “can hold down a job,” “maintains good relations with somebody,” and “isn’t that grossed out by the idea of eating mushrooms.” If someone at least resembles these descriptions, and if they’re over eighteen years old, then we think of them as “adults” and say that they’re “mature.”

You could quibble about which specific characteristics we associate with adulthood, but that’s not what I’m interested in. I’m interested in maturity, and I argue that it doesn’t have anything to do with a set of grown-up tendencies. Maturity has to do with whether or not you’re changing rapidly.

In the early years of a person’s life, they grow both physically and psychologically. Young people change a lot, and if we expect them to keep on changing for a while then we call them “immature.” But then they begin to settle. Change slows, and when it seems like they’ve done the bulk of their own self-discovery then we deem them “mature.” We acknowledge that they might go through additional periods of development later in life; that’s fine. The point is that they’ve left behind the turmoil of youth. They’ve established, to some extent, a trajectory, and they’ll probably stick more or less to it.

I bring all of this up because the weird thing, and stick with me here, is that the world around us doesn’t mature. It keeps changing, even as we mostly stop doing so. The world doesn’t care that we’re not up for changing as much anymore, and actually maybe it seems to change more quickly the older we get, whether because culture actually accelerates over time or because of how we perceive the world as we age. Either way, to some extent each of us wakes up one day, and we’re forty-one, and we’ve shifted down like three gears. Life still feels crazy but we really have trimmed a lot of the extraneous stuff, we’re streamlined, we’ve chosen some kind of course, and maybe we’re even following it a bit. And for some reason, without really realizing it, we kind of expect the world to have chosen a course too. But the world, god bless it, is changing directions all the time, being immature as ever.

A few weeks ago I bought a pair of real dad sneakers. It’s my second consecutive pair of New Balance 998s, purchased this time at a deep discount (forty-six percent off!) from New Balance’s online outlet site. Even with the discount, the shoes cost $99.99, their list price an eye-popping $184.99. While New Balance doesn’t say this outright, I’m pretty sure the reason for the 998’s high sticker price is that it’s made in the United States of America.

Here’s a couple-year-old article that includes photos of one of New Balance’s US factories, which was at the time receiving a sixty-five-million-dollar expansion. The factory employed two hundred and seventy people, and the expansion would raise that number to four hundred and seventy.

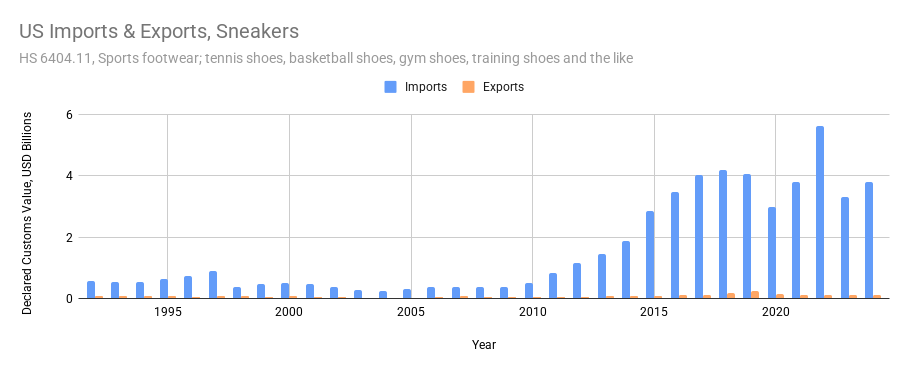

Here’s a chart of sneaker imports and exports, as reported in the US Census’ data from 1992 to 2025. According to Wikipedia, the New Balance 998 was introduced in 1993. According to ImportYeti’s bill of lading data, New Balance’s suppliers are mostly in Vietnam and Indonesia. This advertorial 2021 blog post claims that New Balance has a total annual production of around sixteen million pairs of shoes. Of those, New Balance itself says that they “make or assemble” about four million pairs in the US.

This is all a bit surprising to me: that fully a quarter of New Balance’s sneaker production is made in the US. I do some math, trying to estimate how much of New Balance’s revenue comes from US-made shoes, but I’m not sure what it’s telling me and I end up zooming out to the footwear market as a whole, asking, How many shoes are made in the US overall? One oddly self-assured blog post claims that 99% of the shoes sold in the US are made overseas. I can’t get their math to work out — they claim that we manufactured 25 million pairs of shoes domestically in 2022, and imported an additional 2.7 billion pairs. But the US Census says that we imported $35.5 billion worth of shoes, suggesting an average value of just over $13 per pair. This strikes me as low by a factor of at least two (this detailed set of shoe consumption statistics claims an average sale price of $32.30 per pair), but by now I guess the point has been made: We import a lot more shoes than we make.

Either way; I email New Balance’s PR department and ask them what they think of the tariffs. A week goes by with no response, and when I come back to edit this paragraph it no longer feels relevant to chase them down.

This is partly because I spoke with Oliver the other night, and he expressed skepticism about my sneakers. They are, admittedly, kind of a niche look. So I looked around my life, and tried to think of other American-made things I buy. I have a couple other pairs of American-made shoes — all dressy ones, “loved” in an aspirational way but infrequently worn. I own five or six bikes that were assembled in the US, though to be fair I personally built bike frames for a few years and even then maybe half of their components were made in Taiwan, China, or Japan, and most of the steel and carbon fiber I built the frames out of was imported too. Our dining room chairs were made in Michigan, and my cast iron skillet was made somewhere between Wisconsin and Indiana. I believe our induction range was made in Kentucky. The last five books I read were all printed somewhere in the United States.

Then I try to think of things that I almost never buy the domestic version of. I look for examples slightly less obvious (and less obviously associated with hot-button political issues) than electronics and apparel. Earlier this afternoon, I walked to the hardware store and bought a spool of mason’s twine, which I’ll use to lay out our new deck in a couple of weeks. It’s sitting on the bench across from me, and I walk over and pick it up. It cost $4.99, and was made in China and then distributed by a Brooklyn company called “RWH” who claims, on the label, to “guarantee it for life.” I peel off the shrink-sealed plastic packaging and liberate the paper label. It has no contact information on it, and Googling the distributor’s name produces essentially zero results.

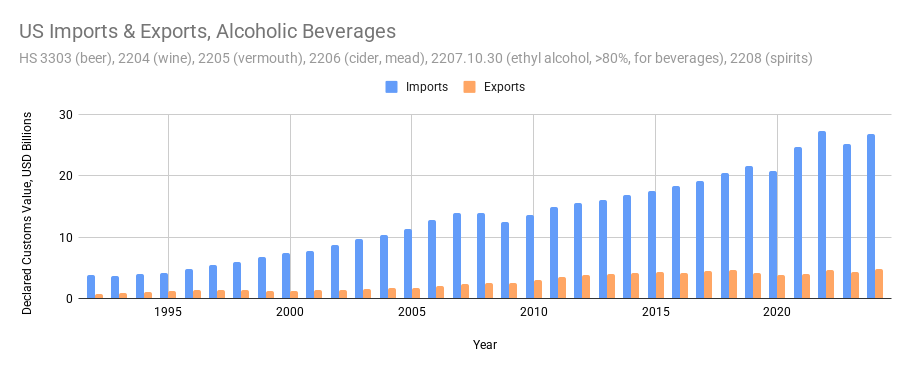

A few years ago I cut down on my alcohol consumption dramatically. I did this just as my interest in amaro, the herbal Italian digestif, was nearing its zenith. Before amaro I spent a while trying different aperitifs, and before that I went through a rather fun rum phase. I think of the liquor store as a place where domestic and imported goods compete on a more or less level playing field. I remember particularly liking an amaro from North Carolina, and my favorite aperitif is produced within walking distance of my house. But when I look at the trade numbers I’m kind of blown away. We import way more booze than we export:

I like Scotch as much as the next guy, I guess, but I tend towards mixed cocktails, and so I buy more bourbon and rye than Scotch. Bourbon is made all over the US but mostly in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Indiana. Scotch is made in Scotland. I don’t, if I’m being honest, have particularly strong feelings about any of these places. I’ve at least eaten a meal in Kentucky, and have spent a few nights each in both Tennessee and Indiana. I took a work trip to Scotland in about 2015. Glasgow (one of the two places where Johnnie Walker is bottled) has around the same population as Louisville, Kentucky (which is about a half hour from the Jim Beam distillery), and the internet seems to support the idea that these two cities have similar costs of living and qualities of life. If two identical products were made in Louisville and Glasgow, and the difference between their respective input costs were negligible, then I think it would be fair to implement policies to encourage people to purchase the one that was made closer — geographically, politically, whatever — to where they live.

A 1.75-liter bottle of Jim Beam costs $36.99 at a local liquor store. A 1.75-liter bottle of Johnnie Walker Red, $39.99. Would it be reasonable to increase the price of Johnnie Walker Red by ten percent? Would $4 convince anyone to switch to bourbon?

I don’t know what Oliver thinks about Jim Beam or Johnnie Walker Red, but I know that he doesn’t really see bourbon as a substitute for Scotch. I could wave my hands and argue that their underlying purposes are identical, but he could counter that I would never make an old fashioned with Scotch. My argument is vulnerable to reasonable objections; I need to look at a different product category.

I decide to make myself a drink. The whiskey I have on hand, which bears the name of a posh Philadelphia neighborhood and is apparently a “Pennsylvania style” rye, is actually distilled in Kentucky.

When I spoke with Alexis Madrigal a few months ago — this was in the innocent days, before any of us were thinking about “reciprocal” tariffs — he shared a nuanced and complex assessment of US-Asian trade, which he calls the Pacific Circuit:

Do I want to pull the plug on the whole thing? I think the answer is no. We live in history; what has happened has happened. The American economy could have developed in a way that was less financialized. We also could have dealt quite differently with American manufacturing. We could have not kept the dollar as strong as we have. We could have done lots of stuff, but we didn't. We instead built this thing, this economy. And I don't know that you can unwind it quite so easily.

I guess I'm also willing to entertain the idea that people have different notions of what’s good — and different ways of executing it. There are all these questions about, like, Did we end up trading American wage growth for asset inflation for the wealthy? Which is probably something we did. But the basic idea was that we wanted Asian economies to be tied to us through their exports. We wanted access to their consumer markets, and we wanted access to their laborers. You can get caught in the details, but we set out to do those things, and we did them. And in so doing, we rebuilt the American polity, too: The economic links then served as bridges for immigration. I mean, big parts of the Bay Area are dominated by Asian communities — the children and the grandchildren of immigrants. I think it's awesome. It’s in keeping with the pluralistic version of America that I like. This complicates my feelings about the Pacific Circuit — it’s a system that’s not just about the manufacturing.

I like to think of myself as someone who enjoys living in history, and I have certainly tried to enjoy living in the globalized, pre-2025 world. If you asked me to compile my ten most treasured memories from my professional life thus far, at least five of them will have occurred at a factory outside of the United States of America. There really is nothing like collaborating with people halfway across the world. It’s inspiring, and radical. When you’re visiting a factory overseas, you’re struck with just how pluralistic the world really is. The people you work with approach shared problems from different trajectories. Their workdays are structured a little differently than yours, and their factories use equipment and tooling that you’re not used to seeing up close, and it seems like nine times out of ten they suggest efficient and elegant solutions that you simply wouldn’t have come up with yourself. Most of all, though, I think about the way that these factories ensconce themselves into their surrounding environments.

One of my all-time favorite scenes: I’m not sure who made the reservation, but the name of the hotel was “Hiyatt Garden Hotel.” Here it is, on Baidu “Panorama” view. I have vague memories of the hotel restaurant, and a picture of a plate of cut fruit, but what I really remember was leaving the hotel and walking around the neighborhood. It was afternoon, and after checking into the hotel we crossed the little highway it was on, walked a block further, and then made a right and headed south. Baidu’s Panorama cars haven’t driven the precise route that I remember taking, but this street scene feels vaguely familiar. We weren’t looking for anything in particular. We had visited our speaker manufacturer elsewhere in Dongguan earlier that day, and the next day we would go back down to Shenzhen to visit SEG, the famed electronics mall. The business-y parts of our trip were, for all practical purposes, over, and we were free to be tourists for the evening. So we walked. The neighborhood was mostly low- and mid-rise apartment buildings. The construction was maybe a couple decades old, nice, neat, very mixed-use. Then at some point — I can’t find it on Baidu Panorama, but it would have been around here — something changed. By this time it was evening, and there was a rush of pedestrian activity, people walking home from work. Something industrial was happening nearby, a shift must have gotten off. The street, which had been narrow, opened up — it wasn’t quite a vest-pocket park, but I remember a small basketball court, and across the court we saw little workshops, their roll-up gates rolled up, spilling fluorescent light into the dusk. We allowed ourselves to be drawn towards them. The first shop we saw had at least five people inside. The video I have of it sweeps from right to left: First a kid, maybe ten or twelve, sitting next to a refrigerator; I think he might have been eating dinner. Then a teen, turning towards me and then walking over to the kid. Then two young men, mid-twenties at most, operating a sinker EDM machine, and finally a guy probably in his thirties, observing and guiding the younger men. Elsewhere in this scene were a surface grinder, a knee mill, and a pink bicycle leaned up against a surface plate.

Anyway, we gestured, and they gestured, and we stepped a few feet into the shop to watch them work. Across the darkened street, some folding chairs had been set up on the basketball court. The building adjoining the basketball court looked like a restaurant, and a few people sat outside. The EDM machine wasn’t running while we stood there, but I got the distinct sense that it was about to, and as we walked further into the neighborhood we saw small fabrication projects in similar stages of completion — things that maybe needed to be delivered to the factory in the morning, so that tomorrow’s shift could run smoothly. A CNC lathe or mill, a few manual machines, and two or three workers under bright lights, metal chips swept into the corners. In one shop a small dog — maybe a husky pup? — lying on its belly on the floor, legs splayed, head turned to look at me. Low plastic stools on the sidewalks in front of the shops, lofted rooms along their back walls. Some of the shops were directly adjacent to similarly small retail stores, their neon or more likely LED signs lit, their doors open, their shelves stocked. There was evidence of children — it seemed like maybe the lofts in the backs of these shops were where the workers’ families lived — and even today I think “how wonderful to grow up in the world, uninsulated from the work your parents do,” and then I wonder whether I’m romanticizing the whole thing way too much. But then I think “no, this was wholesome, this was in some important way sustainable. This little urban space took responsibility for its own externalities.”

Anyway I loved this neighborhood, which was on the eastern side of Chang’an, a township in the city of Dongguan. Wikipedia tells me that Chang’an had a population of 807,000 in 2021, and ChinaDaily tells me that in 2024 the township had a GDP of 100 billion yuan ($13.64 billion). There are two smartphone companies, Oppo and Vivo, which were founded in Chang’an, and together they employ something like eighty thousand people. As a result, in 2024 Chang’an accounted for “one-eighth of the world's total smartphone shipments.”

I don’t have an intuitive sense of what a GDP of $13.64 billion gives you, so I try to find examples of US towns with similar economic outputs. Chico, California has a gross domestic product of $11.7 billion — just a little less than Chang’an. Chico has one-eighth the population of Chang’an. Chico is home to one of my favorite bike component manufacturers, Paul Components, which had a dozen employees in 2022. Chico is also home to Sierra Nevada Brewing Company (about a thousand employees) and a state university (about fourteen thousand students and two thousand employees). I don’t believe I’ve ever been to Chico, but I’m told by Wikipedia that it is “the cultural and economic center of the northern Sacramento Valley.” The National Yo-Yo Museum is in Chico.

Whether we want to keep our Chicos how they are, I think part of the question I’m grappling with is whether we want more Chang’ans in the US. I think I might. Maybe that’s a red herring, though. Maybe I should just look harder for things that we should stop importing and start producing domestically instead.

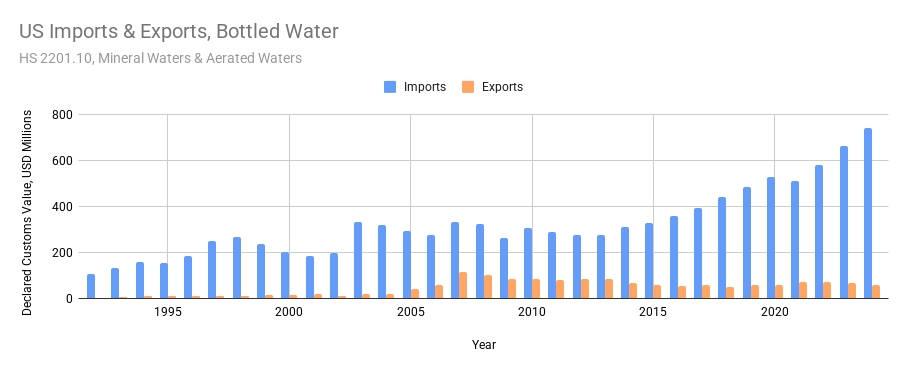

I look up HS Code 2201.10, “Mineral Waters and Aerated Waters.” A company called Natural Waters of Viti — you know them by their brand name, Fiji Water — is one of our biggest importers of 2201.10. Based on publicly available bills of lading, Natural Waters of Viti imports something like 2,260 TEUs per month. How much of them are filled with water isn’t totally clear, but something like two thirds of their imports come from Fiji, where their “single, pristine” water source is located. I’ll spare you the math, which is admittedly shaky, but let’s say that Natural Waters of Viti imports something like eleven million gallons of water per month, or 132 million gallons per year.

By comparison, in 2020 Poland Spring extracted 201 million gallons of water from the Poland Spring aquifer (one of a few they’re permitted to bottle from). I look up import and export data for 2201.10 on the US Census’ trade data website. Again, the disparity is staggering. I don’t think of the US as being particularly arid, but in 2024 we imported twelve times as much bottled water as we exported:

I walk down to the grocery store for tortilla chips and an onion. A few years ago I sat next to a Québécois onion merchant for an hour or so, and she described the onion trade as surprisingly dynamic. Remembering this, I Google the topic, and find an incredible pair of sentences, which I’ve added emphasis to here:

In January 2025, Canada exported Onions mostly to United States (C$8.83M), Netherlands (C$115k), Trinidad and Tobago (C$2.79k), France (C$1.97k), and Saint Pierre and Miquelon (C$600). During the same month, Canada imported Onions mostly from United States (C$18.9M), Mexico (C$9.82M), China (C$9.53M), Peru (C$1.5M), and Spain (C$997k).

Onions coming, onions leaving. Before I leave the grocery store I swing through the beverage aisle, where bottles of Poland Spring and Fiji water share shelf space. By the liter, Fiji water is roughly four times as expensive as Poland Spring.

Bottled water is, incredibly, Fiji’s single biggest export by a factor of more than two. The United States is Fiji’s single biggest export destination by a factor of more than two. In 2024 we imported about a hundred and forty-two million dollars worth of bottled water from Fiji.

(There are so many other things I want to mention about Natural Waters of Viti. The first is that over the first decade or so of its operation, the (American-owned) company didn’t pay the government or people of Fiji anything for the water they extracted from a public, natural aquifer. They fought hard to maintain their effectively tax-exempt status, but starting in 2011 they acceded to a Water Resource Tax of fifteen Fijian cents per liter; in 2023 I believe this was increased to nineteen-and-a-half Fijian cents, about $0.09, per liter. Each liter they import to the US is also subject to a $0.26 per liter import tariff, which applies to all bottled water, regardless of where it’s from. If these tariffs, and the shipping costs the company must incur, seem extravagant to you, consider also that the company apparently consumes over six times as much water as they bottle. But even this pales in comparison with what Natural Waters of Viti’s parent, The Wonderful Company, does in its home state of California. As this troubling 2018 piece describes, The Wonderful Company — which is known mostly for clementines, pomegranates, and pistachios — uses staggering quantities of water in its farming operations. They also somehow own a majority stake, now worth about a billion dollars, in an underground water reservoir which was paid for by the state of California.)

All of this is to say: Bottled water is too obviously a bad example of globalization. It’s too absurd; it won’t teach anyone about the benefits or drawbacks of “reciprocal” tariffs. All it’ll convince you of is that we should ship less bottled water around the world.

I look up what the Fijian Ministry of Trade had to say about the 32% “reciprocal” tariffs we slapped on them a few weeks ago. They seemed offended, and protested on behalf of their kava, turmeric, and ginger exporters. Knowing that bottled water is our biggest Fijian import by a factor of almost three, I try to figure out what our second-biggest Fijian import is. And so I find, at last, 1604.14.3099 — a variety of canned, but not oil-packed, tuna.

“Canned tuna,” I think to myself. “I ate canned tuna today. I wonder where it came from?”

I pull the can out of the recycling bin, find the traceability code, and look it up. My tuna was caught on the west coast of Indonesia last December, and canned on the west coast of Costa Rica. Its brand name, Tonnino, is Italian for “tuna.” Tonnino is made by a Costa Rican company called “Alimentos Prosalud,” which roughly means “healthy foods.” I look up Alimentos Prosalud, and learn that they were spun out of a company called Zapata Petroleum Corporation, which:

- Was founded in 1953, and named after Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata

- ...in Rochester, New York

- ...by future CIA director and US President George H.W. Bush, along with one of his CIA buddies and a few oil scouting and wildcatting guys

- ...and was later used as a purchasing front by the CIA

I can no longer tell if this is a digression. Anyway, Alimentos Prosalud is now “a 100% Costa Rican company.” I see no evidence that its Italianate brand name is anything other than a pretty word they adopted to convince me to buy their fish.

The world is immature. It changes in ways that I don’t approve of, and it does so at times that I deem inappropriate. The world also changes depending on which direction I look at it from. I turn a can of tuna over in my hand, and my entire understanding of it changes. I buy a pair of shoes, make myself a drink, take a sip of water — it all has so much meaning. But every time I think I know what the meaning is, it seems to change.

So. What do I think of the “reciprocal” tariffs?

Well, I think they’re pretty immature, too.