The near-universal comedy of technological failure

The story goes that Thomas Edison ran thousands of failed experiments before landing on a working design for the incandescent light bulb. It’s become a fable, whose lesson is that experimentation and failure are necessary for success. Of course, the story is apocryphal – Edison largely took credit for others’ work in developing the light bulb – and its lesson, while more true than the story, is kind of boring.

I’ve always been more interested in the failed inventions that aren’t just paving stones on the road to success. The kind of attempts that are so bad that you have to wonder “are they serious?” – like a nose stylus for using your phone in the bath when your hands get wet.

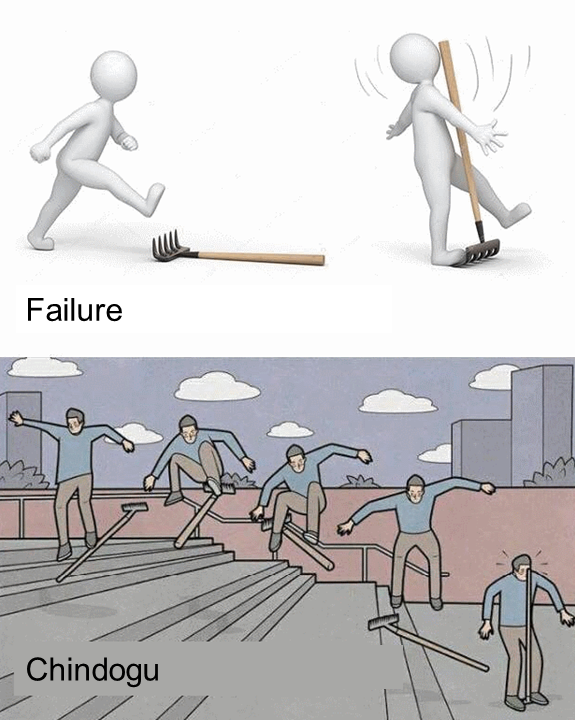

There are many variations on the idea of ‘failed invention.’ Rube Goldberg machines are overly-complicated contraptions, designed to accomplish simple tasks. Kludges and jugaads are hacky devices assembled from what’s available – usually creating something much weirder than if you started from scratch. There’s a whole genre of life hack TikToks where creators, in the quest to create as much content as possible, don’t stop to ask if what they’re creating makes any sense at all. But I’d say the genre of bad invention with the most nuanced and interesting relationship to failure is Chindogu.

Chindogu is a Japanese word meaning “weird tool.” These (almost) useless inventions might address a challenge, but they also create bigger problems. Iconic Chindogu inventions include chopsticks with a fan attached for cooling hot food and a onesie with mop-like fringe, harnessing the untapped crawling power of your baby to clean the floor. While inventions like these are usually not practical for their intended purpose, they can still be charming, evocative, and funny, and give us something that successful inventions can’t. They offer a moment’s deviation from some prescribed path to success, a pause in the slog of value creation, to allow a moment’s worth of weird joy.

The Chindogu Society has published ten underlying – and surprisingly deep – tenets. They espouse an endearing earnestness, speak to the bizarre failures of late-stage capitalism, and underline Chindogu’s appeal across cultural and linguistic divides, offering more interesting musings on failure than most of our fables or motivational posters in the process. The following select tenets and examples of Chindogu and quasi-Chindogu aim to make that point. And if they fail at that, at least they’re funny.

Humor must not be the sole reason for creating Chindogu.

The creation of Chindogu is fundamentally a problem-solving activity. Humor is simply the by-product of finding an elaborate or unconventional solution to a problem. You try your best, you nearly succeed. Then you realize, sardonically, that your problem may not have been all that pressing to begin with.

Chindogu are supposed to be sincere efforts at problem-solving. Take, for example, objects on display at the Museum of Failure. These are products – like spray-on condoms or Colgate brand frozen beef lasagna – that weren’t made to be funny. They were earnest attempts at useful products. But after failing to find a mass market, they succeed in making us laugh.

There is a whole genre of pointless or meta objects that are funny but don’t genuinely try to solve a problem – like upside down jorts, or a watering can that can only water itself. Chindogu is fundamentally about failure. If someone sets out to make a funny object and they succeed, then they don’t have Chindogu – they just have a funny object.

Chindogu are not sor sale.

Chindogu are not tradable commodities. If you accept money for one, you surrender your purity. They must not even be sold as a joke.

Kenji Kawakami, the progenitor of the term Chindogu, is famously anti-capitalist, donating proceeds from his books to charity and refusing to be paid for interviews. He’s said “I despise how everything is turned into a commodity” and “I reject society by laughing at it.” His vision of Chindogu is counter to commercial society in most forms. In Kawakami’s view, Chindogu buck the norm of mass production with bespoke, hand-made objects. Chindogu push back against a world in which everything is appraised in monetary or utilitarian terms; Chindogu are inventions whose only value is to make us laugh.

Chindogu aren’t for sale, either because no one would buy them (in the case of the objects in the museum of failure) or because of their inventors’ higher ideals (in Kawakami’s case).

There must be the spirit of anarchy.

Chindogu are man-made objects that have broken free from the chains of usefulness. They represent freedom of thought and action: The freedom to challenge the suffocating historical dominance of conservative utility; The freedom to be (almost) useless.

It feels sometimes as if everything must have an economic use. No natural resource can go unmined, our every hobby must be monetized or assembled into a compelling personal brand. Even our vacations, the one time we don’t work, are cast as time to recharge to be more productive when we return. In times like these, it’s refreshing to have truly useless objects.

But not everyone shares this perspective. With Silicon Valley mantras like “fail fast, fail often” and the VC approach of assuming 99 failures for one big win, Chindogu-like creations are often produced earnestly as commercial products – like the objects in the Museum of Failure. These efforts cast Chindogu not as purely useless, but as Edisonian failures justified by their importance to some ultimate success. While to some, Chindogu being handmade seems counter to mass production, to others they just look like abandoned prototypes for some eventual mass-produced product.

Even Chindogu that begin as useless may be co-opted by corporations. Artist Craighton Berman’s Instagram, No Commercial Value, is dedicated to amusing but useless designs that, somehow, corporations put to use. I once giggled at his “make-a-size” paper towels with the tagline “pixel accuracy – use only what you need and save the earth.” To me, it seemed like pure Chindogu. So I was surprised that some Instagram commenters said they actually wanted it and, several weeks later, Brawny released “Tear-a-Square” paper towels, letting you “choose the size that fits the task.”

The clearest example of the commercialization of Chindogu is Matty Benedetto’s Unnecessary Inventions. He’s unabashedly commercial, cultivating a strong brand through his Instagram and website, and selling quasi-Chindogu objects, like a jigsaw coffee table, alongside tee shirts, socks, and, perplexingly, a rug of Mark Zuckerberg’s face. With 1.5 million followers he is likely the most successful Chindogu creator today, unseating the anti-capitalist originators of the craft in sheer popularity.

One might read this as a failure of Chindogu and its originators. The art of (almost) useless inventions is not inherently anti-capitalist – it can and has been twisted to serve the systems that it originally set out against. In this way, Chindogu’s failure has a fractal quality. The craft is about objects that fail in their intended goal, and if you zoom out, the practice of Chindogu itself may have failed at its goal.

When Chindogu fail, they give us something – they’re intriguing, funny, or inspiring. And when Chindogu as a practice fails, it can give us something, too. Compromising Chindogu’s values comes with benefits: Matty Benedetto’s business savvy is part of the reason he’s been able to bring Chindogu to such a wide audience; and who cares if Bounty or others pilfered Chindogu – if people want tiny pieces of paper towel, who would deny them?

Chindogu are not propaganda.

Chindogu are innocent. They are made to be used, even though they cannot be used. They should not be created as a perverse or ironic comment on the sorry state of mankind. Make them instead with the best intentions.

Chindogu isn’t intended to be moralizing or didactic; it avoids simple propaganda-like statements like “commercialism is bad.” Even when Matty Benedetto seemed to steal and make money off some free-use Chindogu ideas, the Chindogu Society shrugged their shoulders and said they were just glad more people are making and seeing useless inventions.

That’s not to say there isn’t any contradiction. The Chindogu philosophy seems to include both statements against capitalism and statements against making such statements. “The suffocating historical dominance of conservative utility” definitely sounds like a “comment on the sorry state of mankind,” for example. For the most part, I think Chindogu threads the needle and does both things at once – and even if it doesn’t, it’s all a joke anyway.

The Society is accurately describing Chindogu’s unique brand of humor: light, joyful, earnest; never didactic, and often a bit counter-cultural. Take Simone Giertz’s “shitty robots” as an example, like this one that smears lipstick all over her face. It gestures toward issues of gender, and automation, but it’s not a cultural critique – it’s just a failed invention that gets a laugh.

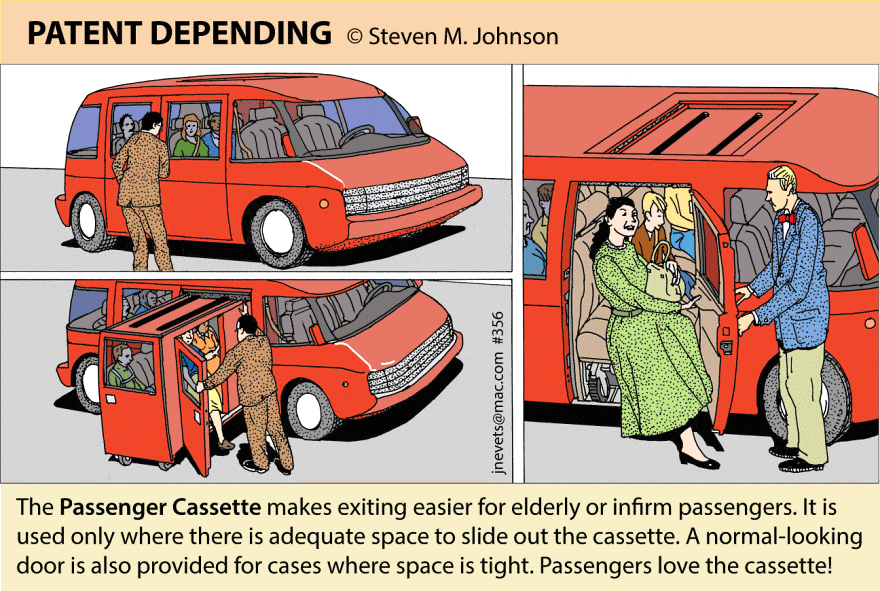

This is another balancing act. Chindogu have to have some ambition – they must make sincere efforts to solve a problem. But there’s an upper bound on Chindogu’s ambitions – they can’t aim to solve problems too big. Take Steven Johnson’s “bizarre inventions.” He’s designed two person toilets, TSA-approved clear shoes, and a “passenger cassette” to make it easier to get people in and out of cars. They easily avoid moralizing and instead focus on design challenges and quirky, laughable solutions. They also keep their sights on small problems. They’re not trying to change car culture in the United States or to fix the surveillance state.

This rightsizing of ambition dovetails with another tenet. Chindogu do not aim to solve abstract, systemic problems so much as they are human-scale and rooted in people’s everyday experience.

Chindogu are tools for everyday life.

Chindogu are a form of nonverbal communication understandable to everyone. Everywhere. Specialised or technical inventions, like a three-handled sprocket loosener for drainpipes centered between two under-the-sink cabinet doors (the uselessness of which will only be appreciated by plumbers), do not count.

For Chindogu to be funny, they have to be relatable. For example, a device that allows the wearer to escape an undesirable social situation by making it look like they wet their pants: absurd as it may be, we’ve all been there. Successful Chindogu are more universal than verbal jokes, transcending language and cutting across cultures. Khaby Lame became the most followed Tik Tok creator on earth through the universal, wordless comedy of viral life hacks he calls out as Chindogu. Many of his videos, like the one below, are advertisements for dumb life hacks or inventions, stitched together with clips of Lame mocking them by showing an easier, usually more traditional way.

If one were asked to name universal comedy, they might suggest Charlie Chaplin’s silent slapstick. Chindogu is the natural technological analog, conjuring, without words, an earnest desire and a funny failure to achieve it.

Like Charlie Chaplin, Chindogu don’t fail lamely. There’s always some kernel of excellence. Charlie Chaplin might gracefully mime out something dumb, and Chindogu have a grace to their dumbness, too. In order to be funny, they can’t be pure garbage – there must be some recognizably clever idea, or skill in carrying out a bad idea.

And in this way again, Chindogu as a craft reflects Chindogu objects. The Chindogu society articulates tenets that are simultaneously beautiful and precise, maybe contradictory and begging to be broken. Chindogu isn’t just the funny, evocative, and charming craft of failure; it is a funny, evocative, and charming failure itself. Sure, sometimes Chindogu-type failures align with the Edison fable – they teach us why something doesn’t work, or they highlight a kernel of excellence that can carry us to our next success. But often Chindogu-type failures forego success altogether, reveling in the anarchic joy of leaving value creation behind, and simply make us laugh.