Surgery Simulation AMA with Andrew Edman

There is such joy and excitement in putting a product out in the world, but linear lifecycle design means that most products, no matter how spectacular, are destined for a landfill. Andrew Edman, a jack-of-all-trades designer and engineer, is acutely aware of this tension and transitioned from a career in consumer product design to a role with the Immersive Design Systems team at Boston Children’s Hospital. Here, Andrew works with clinicians to develop and fabricate high-haptic surgical simulation trainers – which is to say he makes surgical training models that are highly realistic in both look and feel. The team he works on also develops medical devices tailored to patient needs within the hospital. The work is somewhat uncanny and more than a little bit gorey; be warned that this interview includes photos of (simulated) blood, organs, and bones.

Andrew works across industrial design, engineering, and manufacturing, and before joining Boston Children’s Hospital he ran a small product development agency and worked at Formlabs. Outside of his day job, Andrew interrogates the strange and wonderful relationships that we form with the material world through side projects like ARTIFACT Zine and BL0T2046.

Our conversation with Andrew covered the ins and outs of designing and building surgical trainers, how the clinical setting differs from the product design world, and the philosophies that underpin his work. The conversation has been condensed and lightly edited.

Hillary Predko: Your work at Immersive Design Systems involves making very lifelike models for surgeries and other medical procedures, like full silicone bodies with tubes for simulated blood. How does the team decide what is going to be simulated and what is the lifecycle of a project? What degree of realism are you aiming for?

Andrew Edman: Our work is nearly always clinician-collaborator-led, so a surgeon, nurse, or other clinical worker will come to our team with a problem. It might be that they need simulated tissues to evaluate a medical device concept, or that they are training surgery fellows or a nursing team on how to do a specific procedure, or it could be in support of a team-based simulation scenario like an unexpected bleeding event during a routine surgery.

The level of realism is also usually based on the request, though we target “better than absolutely required” levels of fidelity. Surgeons are often very focused on the haptics – is the simulated tissue or structure mechanically responding as they would expect it to? So we spend a lot of time dialing in materials to give them what they expect, and at this point, we have a decent starter library of materials to serve as a baseline when we get a request from a new collaborator. We also focus on things like adhesion: how much does structure X stick to Y, how easy is it to separate and mobilize with dissection, etc.

In terms of the lifecycle, we have some trainers that go from start to finish in a few weeks and some that stretch out over years – those are unique if you're used to commercial product development. Our clinical collaborator client model is more like an architecture firm, and we have clients with budgets where they can keep making changes as long as they want to. We also get requests for more traditional product stuff: medical device concepts, other equipment for use in clinical space, or a custom device for a patient.

HP: Oh wild, so you've got a catalog of what materials will feel like cartilage vs. skin vs. bone?

AE: Yeah, we have cartilage recipes, miscellaneous muscle recipes, fat, different kinds of bone, vessel materials, etc. We are in a funny position as engineers from a materials standpoint: generally, you don't want your product to break or get damaged, but we are trying to get materials that fail as close to reality as possible. For us, that means we are intentionally making some really delicate stuff sometimes. For instance, our team has a fetoscopic (!) surgery trainer [which allows surgeons to operate on fetuses in utero] under development – you can imagine how thin and fragile fetal tissues in utero are!

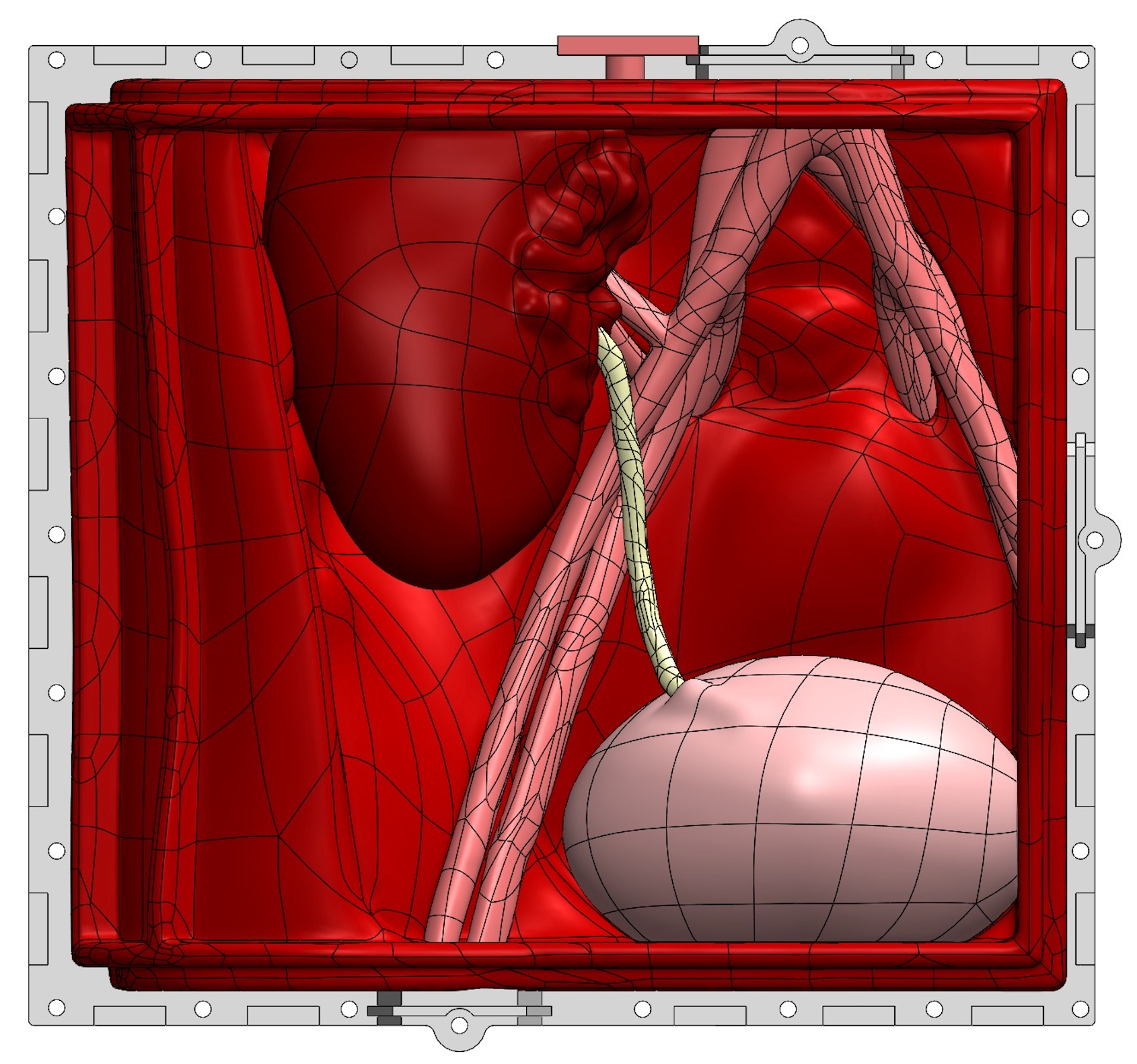

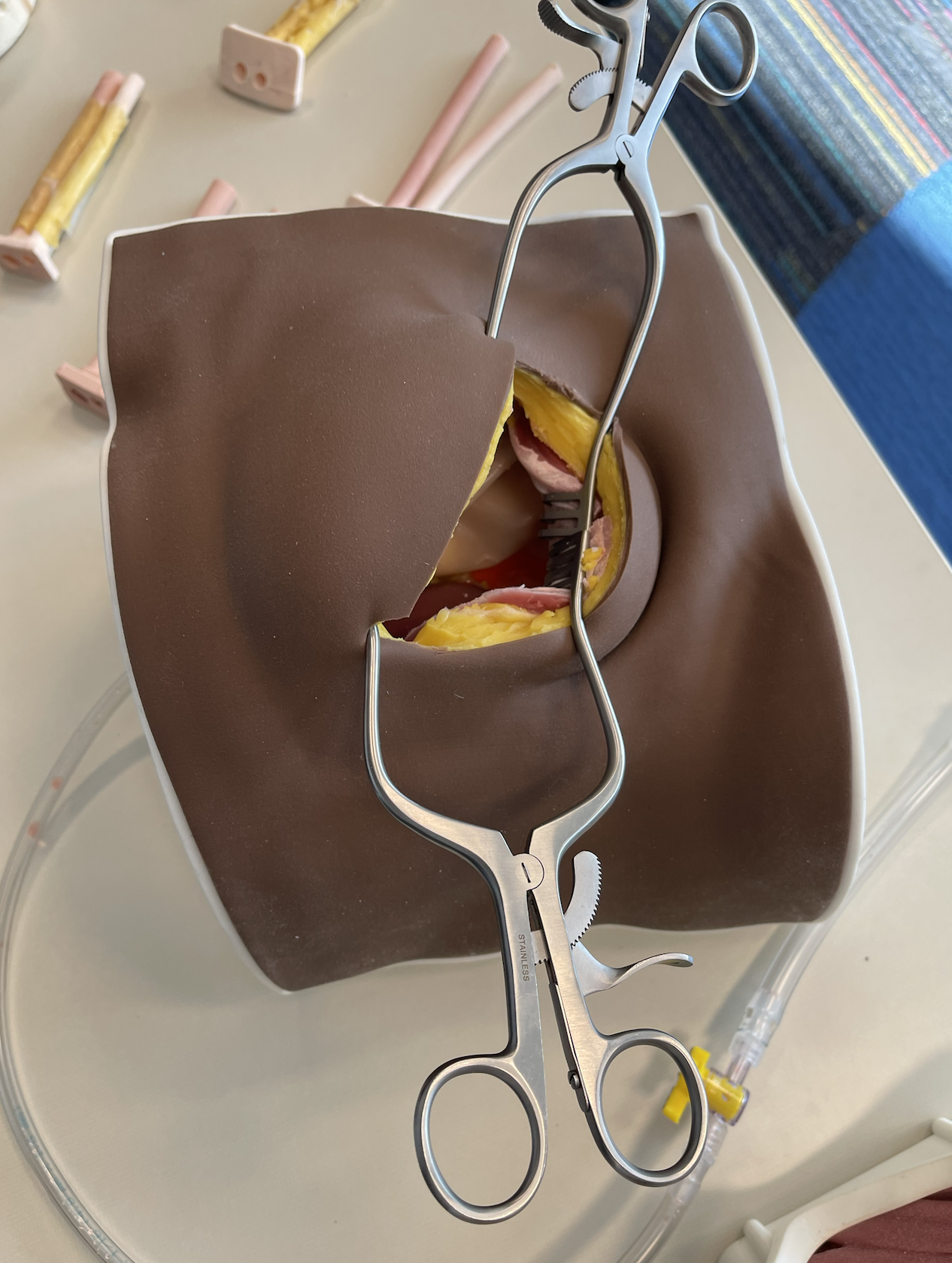

"This is a full simulation scenario trainer developed from 0 to complete in ~5 weeks. In this scenario, the clinical team is performing a revision surgery after a complication from a kidney transplant. Then bam, we turn on the surprise bleeding to simulate accidentally nicking a major vessel." Photo credit: Andrew Edman.

HP: I know there is some digital simulation coming out of your lab as well, but it seems like these material simulations can hit a lot of marks that would be functionally impossible in VR.

AE: We have a VR/AR team and their work to date has touched on everything except the cutting, mobilizing, and stitching aspects of surgery. So, things like VR trainers to help scrub nurses get faster at selecting and handing off instruments work better than trying to simulate the cardiac surgeries themselves.

Spencer Wright: I’m curious about how you’ve adapted to the culture of your current job after working on consumer and small business products. Those seem from the outside as very different industries, with different personality types and operating rhythms. Have you found that to be the case? And what have you had to adapt/what has stayed the same in the way you structure your time and effort?

AE: Yeah, it's a very different environment in so many ways. Decisions about what to do, where to focus, and where value can be maximized are much more complex in a non-profit in my experience – it's not an obvious “what will make us the most money” or “will this make money.”

Some clinicians are focused on training and publishing, some really want to pursue commercialization. And our clinician access is so limited – they are just incredibly busy people so you have to be really strategic about what features to resolve or test in those limited windows we get.

Alex Numann: Do you have any medical training or background, or just what you've learned absorbed throughout projects over time? I recently designed a trainer for laparoscopic surgery on infants and I always joke about slowly earning an unaccredited medical degree.

AE: Yeah, I definitely can get to feeling like I’m at least a medieval-level doctor or something. I had some exposure to medical device development from my commercial product development years but not a lot. I also had some basic anatomy from art school but with every project at the hospital, I'm learning new, sometimes horrifying, things about the body.

HP: What is your favorite device or simulation you've made in the lab?

AE: That's a tough one, probably this device that was pretty simple mechanically but high stakes for patients. A bit of background: there's a piece of equipment from this company Berlin Heart called an IKUS machine. It is connected to the patient via tubes and an implanted device, and it pumps their blood for them. With this device, the patient can be in ambulatory condition, and if they are, you want them walking around regularly to keep them strong and healthy for transplant surgery down the line. But that patient also is attached to an IV pole with medicine pumps, so moving this IKUS cart, the IV pole, and (in our case) a young patient down hospital corridors is very challenging and not without risks.

The cardiac nurses came to our team and asked us to essentially put the IV pole on the cart so they had one thing to push down the hall. It's basically saddle-bag-style brackets for the IV pole and a stainless steel plate connecting them to the IKUS cart itself. So mechanical design-wise it is very simple, but it’s critical equipment so we had to do every risk analysis and mitigation possible. Because it was a new device and had the potential to introduce risks, any time it needed to be switched over (to another IKUS cart when the other was sent in for preventative maintenance), one of our engineers would do the switchover. The patient's family was so grateful for the device and the first time we went to change it over they were really worried we were taking it away. Seeing positive impact and quality of life stuff get better for patients is really the best part of the job.

Jason Luther: Looking back on your career so far, are there any key events or experiences that led you to where you are now? Would your younger self be surprised that this is what you're doing?

AE: Oh man, it's a windy path and I think my younger self would be surprised but able to make sense of it. I was super into special effects stuff as a kid, then I learned you make terrible money as a practical effects person and I was like, “Okay, I'm out.” But I've been into building, tinkering, and designing stuff from a pretty young age so there's that throughline. I lucked into a cool but sometimes grueling job in a prototype shop in high school, that was definitely a trajectory changer even if I didn't fully realize it at the time.

Eric Andersson: What's the wackiest 3D printing application you ever saw at Formlabs?

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now