We’ve recently been admiring photos of a friend’s new kitchen. The cabinets and drawers are pale, clear-coated plywood, the grain visible and made a key aesthetic feature. Along the cupboard’s vertical planes are even, contrasting striations of birch end grain, interrupting the wooden facade and making the panel’s construction visible. These layered ply edges are also visible when you open a cupboard or drawer, instilling a sense of edgy, playful minimalism. This particular type of ply, with its chunky weight and visible edges, is a mainstay of contemporary cabinetry: Baltic birch.

Plywood itself is nothing new; first patented in 1865, it has become an omnipresent commodity building material, used for everything from furniture to film sets. But plywood hasn’t always been the kind of thing you showed off. Oftentimes its exposed edges are covered with veneers or otherwise kept out of sight. The rise in popularity of Baltic birch and similarly constructed ply points towards a shift in popular practice and indeed to the shifting tides of taste and authenticity. Increasingly, edges are exposed, wavy-grained ply surfaces are out and proud, and entire rooms are built to show off what would previously be hidden.

So much of the built environment relies on wood — from solid hardwood boards and structural 2x4s to the often heavily processed paper products (Formica, for instance) used in modern buildings. Plywood sits somewhere in the middle of the spectrum of woodyness. It’s a wood product that looks like wood, with grain on display, the differences between each sheet reflecting the unique trees they were cut from. But plywood isn’t just wood, and much like chipboard or MDF it is a composite product, an industrially produced commodity rather than a pure natural resource. In this way, plywood is more like concrete or steel than hardwood or stone: base materials transformed through the addition of other substances and technical processes to become a building block of the modern world.

Plywood is a wood panel product made from at least three veneer layers, each layer stacked cross-grain to the layer above and below it, bound together under pressure with layers of glue. While the practice of cross-graining veneer dates back thousands of years, the emergence of modern plywood dates to the 19th century — a product of the Industrial Revolution. Its development was enabled by a series of key technological advancements: steam powered engines, the veneer rotary cutter, advancements in glues and resins and the hydraulic hot-plate press.

The process for making plywood hasn’t changed much conceptually since the 19th century, although modern production makes use of significant automation. Then as now, a typical ply production process sees a log de-barked and heated, usually by soaking in hot water or steaming. It’s then cut into shorter logs of a specific length, called “bolts,” to fit a veneer rotary cutter. The rotary cutter peels the log into thin, long veneer sheets, unraveling the log onto a conveyor belt like a giant roll of paper towels. These continuous sheets of veneer are cut to smaller sizes and for some products, any imperfections or knots are cut out and patched. The required number of veneers — from one or multiple types of wood — are stacked on top of each other, covered in layers of glue and then put through a press to bind them together, either into flat sheets or molded shapes for products like furniture or drum kits.

Plywood sheets are strong, with each layer adding additional strength and rigidity. While a tree’s cellular structure gives wood incredible strength in one direction, the cross-lamination process — where the grain of each ply is set at an angle to the one above and below it — means that in plywood, strength goes both ways. And unlike solid wood products which are restrained by the diameter of its source material, plywood’s status as a sheet product makes it a good fit for applications requiring strength and structure — including cabinets, wall lining and roof sheathing.

Still, there is huge variance in ply — the type of wood chosen, the thickness and grade of veneer, the number of plies, and the type of glue all contribute to the final properties of the product. Typically, the two outer veneers of plywood are very thin, with thicker plies in the middle of the wood sandwich. The inner plies can vary in composition, with many products using softer woods or even composite chip layers, while the thin outer veneers are often made from expensive (and aesthetically desirable) hardwoods like maple, oak, or cherry. In many cases veneer is also used to cover any exposed edges, to give the product an illusion of being made from solid wood.

Despite the huge variation in the plywood available, one type has an outsized reputation, known by name and reputation by many makers, builders and architects: Baltic birch. You’ve probably seen it, even if you can’t name it. Widely used for cabinetry, Baltic birch is 100% hardwood, made of uniform birch layers that give a pronounced stripey look at its edge. The all-hardwood nature of Baltic birch, and the uniform thickness of its plies, differentiates it from most conventional plywood. Baltic birch can stand up to rougher treatment, and is less prone to chipping or sanding damage.

For American woodworkers, one easy way to spot Baltic birch is its form factor. Most plywood for the US market is sold in 4 ft x 8 ft rectangular sheets, whereas Baltic birch comes in 1525 mm x 1525 mm squares (a measurement commonly approximated as 5 ft x 5 ft). Similarly, the thickness of the sheets is resolutely metric (9 mm, 12 mm, and 18 mm are all common), although it too is often listed in imperial thicknesses.

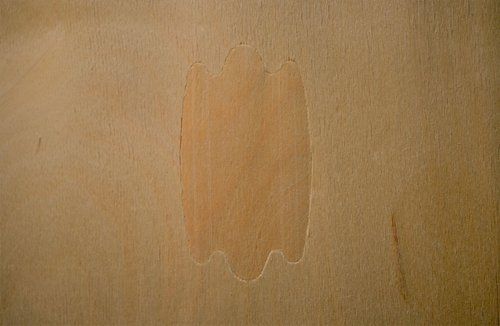

Looking closer, Baltic birch is identifiable by – and loved for – its voidless nature: any imperfections in the plies are cut out, and the resulting holes are patched with unblemished wood. This contributes to a product that has virtually no internal voids, giving it an aesthetically pleasing edge that’s strong enough to be glued. The solid interior also makes Baltic birch well suited to anchoring screws or dovetail joints.

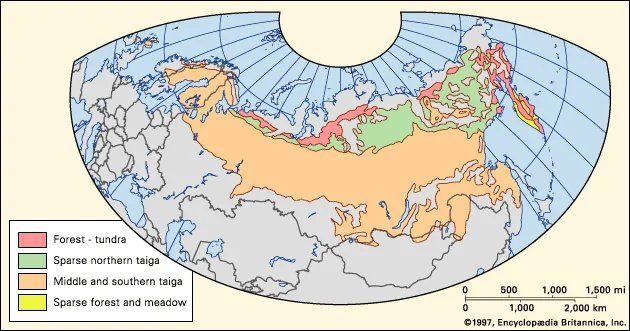

As the name suggests, Baltic birch comes from the Baltic region — primarily Russia, but also Finland, where silver birch is the national tree. Baltic birch is a general designation rather than a specific species (silver birch, white bark birch, and Siberian birch are all commonly marketed as Baltic birch). The same product is also sometimes sold as “Finnish birch” or “Russian birch,” and it’s unclear exactly why “Baltic” birch was the name that stuck. Speculation abounds, though — in his 1993 book Tage Frid Teaches Woodworking, author Frid notes that “When it was first imported the Russians and Americans were not on friendly terms; so rather than call it Russian plywood, the Americans named it after the Baltic sea, to which the Russians have access.” However, while changes in geopolitical allegiances may well have made Russia-branded products undesirable at certain moments, it is likely that the appellation “Baltic” birch was applied to all birch imports from the region even before contemporary Baltic birch was popularized or imported. A 1928 newspaper advertisement for a timber retailer lists products including “Three-ply Veneer in Oak, Cottonwood, Oregon, Hoopine, Baltic Birch”.

The current popularity of Baltic birch in fine woodworking applications is the culmination of a century and a half of evolving technologies, aesthetics, and approaches to craft. Its appeal today is partly in its inbetweenness, its appearance as simultaneously a natural material and an industrial one. Baltic birch succeeds as a synthesis, retaining some of the aura and coziness of hardwood while reading as a visibly industrial, modern material. As such, it is also a synthesis of two conflicting schools of thought about “authenticity” in building materials, and through it we can chart the evolution of a conversation about truth in materials that began with the Industrial Revolution. Baltic birch is a natural, mass-produced miracle.

Throughout its modern incarnations, plywood has mostly been considered a rough-and-ready material: affordable and extremely useful, but less attractive and often lower quality compared with solid hardwood. For most domestic cabinet makers and DIYers, plywood — especially its edges — didn’t used to be the kind of thing you show off. Its visual qualities — the large-format whorls and swirls on its outer surfaces, and the variegated and sometimes splinter-prone end cuts where the stacked plies are visible — were generally undesirable for fine woodworking purposes.

This distaste hearkens back to the early days of the modern plywood industry, when furniture makers were extremely distrustful of ply. In their book Bent Ply, authors Dung Ngo and Eric Pfiffer note that “Woodworkers and furniture factories alike dismissed the new material as ‘veneered stock’ or ‘pasted boards,’ a dishonest product that was inferior to solid wood.” Solid wood, especially hardwood, was the accepted standard for quality furniture, and it embodied a long history of craft and cabinetry. Wood stands the test of time, and woodworking techniques had been honed over centuries of practice and apprenticeship and innovation. In contrast, plywood was seen as an ersatz substitute, a lie in the shape of a board. Ngo and Pfiffer continue, “If used at all in the furniture trade, plywood was employed for hidden parts such as case backs and drawer bottoms ” — a convention that lasted decades.

In the early twentieth century, the very aspects that had always made wood so appealing to cabinetmakers and high-end furniture makers — its authenticity, honesty, and warmth — became a liability in some quarters. In the 1920s and 30s, the pioneering modernist designers of the Bauhaus school turned their attention towards industrial materials like sheet metal and tubular steel, in order to better harness the ideals of mass production and unadorned simplicity. Many came to consider wood — including plywood — too constrained by its associations as a “traditional material,” too beholden to the past, not enough of a blank slate. The influence of this transition was felt widely, and even architect Le Courbousier, who had previously embraced the classic French bentwood Thonet chair and deployed them frequently in his buildings, soon came to claim that wood’s freighting with historic associations “limited the scope of the designer’s initiative.” As Le Courbousier saw it, this shift away from tradition was part of a bigger transformation of the stuff of life. In 1929, he wrote: “A new term has replaced the old word furniture, which stood for fossilizing traditions and limited utilization. That new term is equipment, which implies the logical classification of the various elements necessary to run a house that results from their practical analysis.”

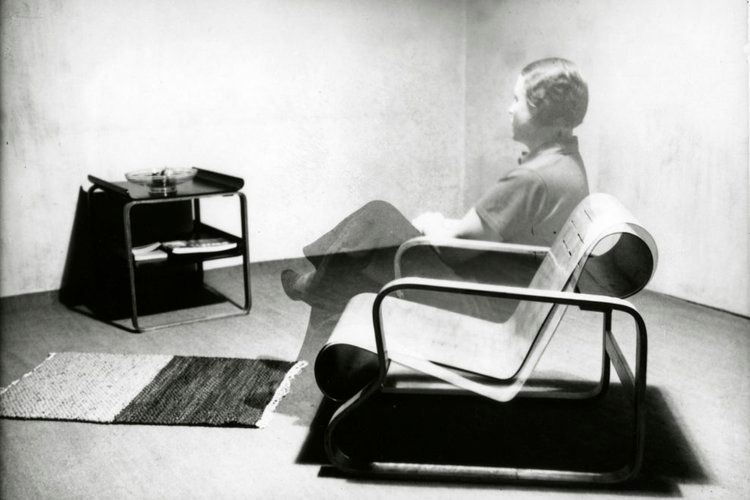

But as Ngo and Pfeiffer describe, not all the designers and furniture makers of the time were convinced that modern furniture required a total abandonment of “natural” or historic materials like wood or plywood. Finnish architect and designer Alvar Aalto broke from the functionalism of the era, insisting that wood was a more humane material than steel, and started experimenting with bent plywood after gaining access to a stock of German-imported beech wood originally intended for bicycle manufacture. Later, in the 1930s Aalto and his production partners turned to Finnish birch, intent on creating designs that would feature and celebrate the country’s plentiful local forests, as former employee Marja-Liisa Parko relates in the 1985 book Alvar Aalto Furniture. He also created wooden collage experiments that expose and celebrate the beauty of plywood itself as a thoroughly modern industrial material imbued with a patriotic Finnish glow.

Aalto’s insistence on plywood as both industrial and humanistic, and his desire to tie modern furniture design to his home country’s primary industries, points forward towards the more recent rise of Baltic birch. As Aalto rose to fame, other designers (including, famously, Charles and Ray Eames) also experimented with plywood, putting its whorled surfaces and even its stacked ply ends on display in showrooms, model homes, and living rooms around the world. Aalto’s experiments with aligning high quality ply to the Baltic regions was also successful, and as his designs became widely known, so did Finnish (and, more broadly, Baltic) birchwood.

Today, Baltic birch is a go-to “shop ply” which has wide popularity with contemporary cabinet makers, architects and interior designers and is used in everything from engineered flooring to childrens’ toys. Compared with other plywoods, it is far less likely to be hidden away, and designers and makers tend to have no qualms putting its robust, striated edges on display. In this way, Baltic birch embodies a contemporary approach to self-conscious “authenticity,” moving away from the modernist ideal of the home as a purely functional machine for living, towards an approach to interiors that combines warmth and comfort with “honest” materials that reveal their origins and play with high and low culture.

However, despite the demand for Baltic birch, the current war in Ukraine and subsequent boycotts and sanctions on Russian products has led to a drying up of supply. Where Baltic birch is still available, prices have increased significantly. The impacts have been significant: Russia is the overall largest exporter of wood products in the world, and Russian product makes up about 10% of the world’s plywood market, so builders and hobbyists alike are feeling the pinch. Other all-hardwood voidless plywoods are available — American companies produce high quality plywood sheets like ApplePly and Europly (which despite the name is produced by North Carolina’s Columbia Forest Products). But they aren’t able to compete on volume or price — Russia’s huge boreal birch forests, massive production capacity, and different labor conditions enable a high quality product at a lower price point. And with the sanctions and supply problems restricting the flow of Russian birch, American producers aren’t able to keep up with demand. It’s nearly impossible to find ApplePly or Europly in stock anywhere.

All of this adds up to an intractable problem for the people that rely on Baltic birch for cabinetry, flooring, and other applications. According to lumber industry expert Shannon Rogers, there is no ideal alternative to Baltic birch. The competitors are currently too expensive, and finding a way to bring an equivalent affordable product to market is too big a risk. Currently, it is unclear how long the war and attendant sanctions and supply chain challenges will last, and whether Baltic birch imports will bounce back quickly afterwards.

Commodity or “primary” exports like timber, meat, or linen, are inexorably tied up with national identity, nationalism, and geopolitical events. Aalto recognized this when he mobilized Finland’s national pride in its birch forests with his bentwood furniture, tying together a prized primary material with sophisticated industrial processes. Today, as Russia’s militarism and unjustified invasion casts a negative light (and strict sanctions) on its exports, the woodworkers and designers that had come to rely on Baltic birch are left scrambling for an alternative. No commodities are “natural”, and none exist outside of contemporary circuits of production and supply.-Entangled as they are with resource extraction and dependent on some degree of supply chain opacity, commodity building materials develop murky and often troubling relationships with politics, economics, culture, and sustainability. In 2022, Baltic birch is particularly murky: a fraught but aesthetically compelling composite of nature, culture, and politics.

—

We are grateful to Dung Ngo and Eric Pfiffer’s book Bent Ply — a trove of information about plywood furniture and its place in 20th century design which we recommend to anyone looking to dig further into the topic.