I had been preparing for weeks to talk with Alexis Madrigal about Oakland, and basically as soon as I got into his car, he was telling me other people’s plans for the city. This is, in many ways, the central theme of his new book, The Pacific Circuit, which I had come to the Bay Area to discuss with him. “Their idea for this place—really since the 1950s—has been that it is a hub of transport. You can totally imagine it: Between Jack London Square and the Port of Oakland, you can have multi-modal transportation for everyone. You’ve got the freight trains, you’ve got the ferry that runs to San Francisco and Alameda... and, like, right there is the Oakland Estuary.” Alexis had picked me up from the Amtrak station at Jack London Square, and by this point we were pointed south on Adeline, facing the Oakland Estuary but not yet seeing the ferries and container ships that use it. Then the road lifted us up and over at least six sets of train tracks, and the visual landscape changed dramatically. Moments earlier we had been in a relatively quiet neighborhood: There are healthy bike lanes on both sides of Third Street, which has a warm and fairly walkable feeling. But as Adeline lowered us back down to ground level we found ourselves surrounded by semi-tractors, with a canyon wall of shipping containers beyond them to our left. To our right, out the passenger window, a bright red curb separated the road from a continuous bed of crushed rock, which was striped periodically with train tracks. The land seemed predestined to become infrastructure, as if the rail tracks were part of the archaeological record, the roadway cut into the gravel after the naturally-occurring railroad bed was discovered.

This was an illusion. As Alexis writes in The Pacific Circuit, the infrastructure that exists today in West Oakland was put there by people, and its location, and the physical goods that are transported through it, have had both neighborhood- and society-altering consequences.

I had read about a third of The Pacific Circuit back home in New York, and a third on an airplane to Reno, and a third on my own multi-modal trip down to Oakland. I came into the book thinking about Containers, the influential podcast that Alexis produced in 2017, and which ultimately resulted in about a decade’s worth of research on his part. But The Pacific Circuit is much more personal, and intimate, than I remember Containers being. It’s about globalization, sure, but it’s also a fine-grained study of how a once-vibrant neighborhood—the Prescott section of West Oakland—is affected when one of the most important container ports in the world is built directly adjacent to it. More broadly, it’s a book about the complex relationship between low-cost import goods and the places where those imports first touch American soil. And to better understand it, I had asked Alexis to show me the actual place where that happens.

So we drove past Schnitzer Steel, a recycling company whose “mega-shredder” can apparently handle “end-of-life automobiles, appliances, and other recyclable metal-containing items.” We passed Matson, the shipping company whose Oakland-to-Hawaii route was key in establishing the Port of Oakland’s early role in containerized shipping. At this point Alexis’ hatchback was one of the few passenger cars in sight, and the scene outside our windows was a bricolage of colorful rectangular boxes, each painted with the name of another shipping company. Trucks were everywhere—drayage trucks, as Alexis pointed out, hired at punishingly low rates for short-distance hauls between the port and a nearby warehouse or transfer depot. Then, at a bend in the road, we turned left, and suddenly we entered a small park that opened up onto some of the only natural-looking coastline (it was actually created from excavated fill) in miles. Down we drove, towards the bay, with a chain-link fence visible behind the pitiful-looking shrubs to our left. Beyond the chain-link fence was the Oakland International Container Terminal, and on our final approach to the bay its great white gantry cranes rose to loom over us. The car slowed to a stop, not quite in a parking space; the park was empty, and this was just a brief pause in our tour. Alexis gestured towards the west, his hand sweeping from left to right. “This is the part that blew my mind,” he said. “It’s this view, right here: On this side you’ve got these ships being actively loaded and unloaded. But then you’ve got the whole Peninsula, with Silicon Valley down there, running into gleaming downtown San Francisco. This was the view that really began all of this, because you can see all these things, all tied into each other.”

We drove on, passing between the Nutter port (a reasonably modern container port) and Cool Port (where perishable goods are transferred between refrigerated containers, trucks, and rail cars), then took 7th Street back towards West Oakland. To get there, 7th Street had been trenched underneath I-880, and as we reemerged at surface level we were shaded from our right by a massive USPS sorting facility, and from above by the elevated BART tracks. To our left, on the sunny side of the street, were old West Oakland’s storied cultural institutions: Esther’s Orbit Room, Slim Jenkins Court. These places bustled with activity in the mid-twentieth century, but were then overshadowed, redlined, and choked out by all the negative externalities brought by the port. “It’s amazing to consider what this place used to be,” Alexis said. “And now, it’s pretty empty.”

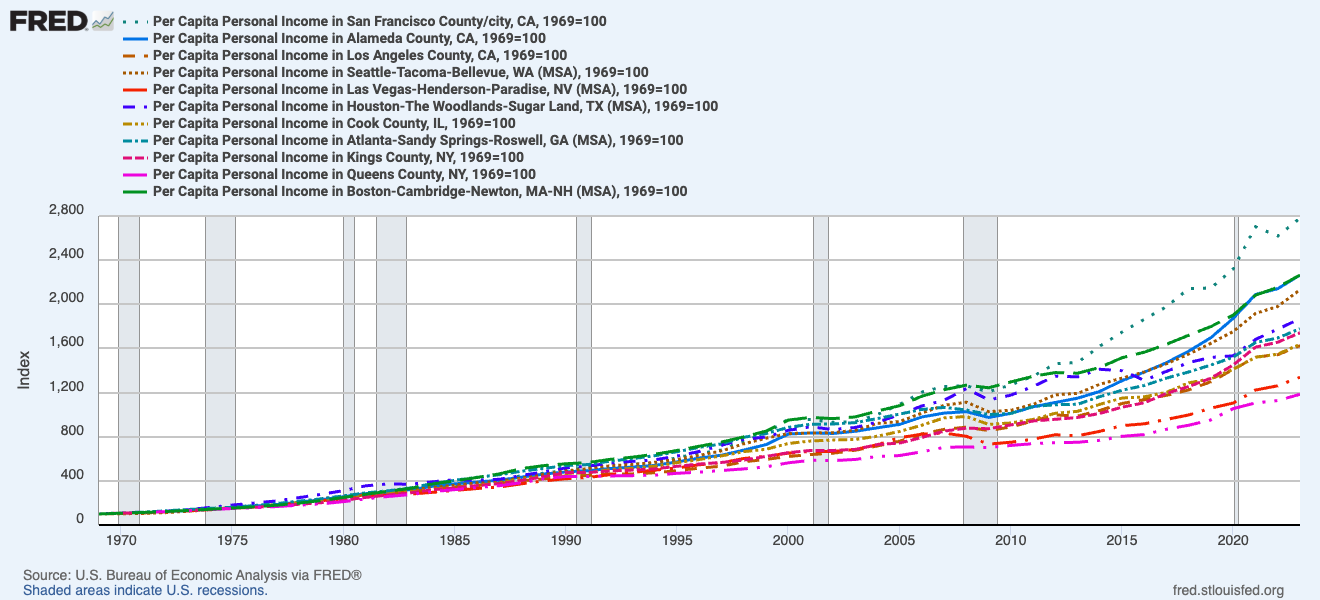

As I read The Pacific Circuit I found myself thinking of globalization as a new circulatory system, surgically inserted into a living body. The Port of Oakland, I figured, was some sort of recently-invented artificial heart, and ever since Matson installed the first 113-foot-tall crane there in 1958, it has been pumping hard. In 1948, the US imported 1.5 billion dollars worth of goods from Asia. In 1990 that number had increased to 200 billion, and in 2020 it was a trillion—a total increase of more than 665%. This trade remade our consumer economy, of course, and it spurred rapid industrialization in Asia, and it played a big role in the Bay Area’s prosperity and global cultural influence. It also, obviously, required entirely new systems for moving goods from one place to another. In concrete terms this meant deep, navigable harbors on the West Coast of the US; it meant colorful and iconic gantry cranes at these ports. It meant massive parking lots to store containers while they’re waiting to be picked up, and scores of low-paid drayage truckers to bring the containers to a warehouse or rail spur, and intermodal train cars to bring them elsewhere in the country. All of this infrastructure, I dreamed, could be thought of as a totally new vasculature, which was grafted, often without much pageantry or any foresight at all, onto our cities. West Oakland is not the only place where this happened: Similar stories could be told, I’m sure, about the container terminals at Bayonne, New Jersey, and Houston, Texas, and Savannah, Georgia. Before containerization and its dramatic increase in global trade, these places all had commercial and cultural pulses of their own. But as Alexis writes, the “people who ran our cities, gazing upon the potential of Asia, chose to sacrifice” neighborhoods like West Oakland. They neglected and then ultimately bulldozed these once-vibrant communities in the hopes of more efficient—and mostly uninhabitable—infrastructural landscapes. The effect, as Alexis writes, was decidedly negative: “Regular working people’s incomes stagnated, only partially offset by the falling prices for many consumer goods. Oakland and places like it entered a period of sustained decline.”

We turned right on Peralta and then continued onto Lewis, driving a loop around a cute, low-slung area that had been saved from 7th Street’s fate when a community group purchased property, en masse and in cash, from the Southern-Pacific Railroad. “There was a literal red line drawn around this neighborhood,” Alexis told me as we drove up another well-groomed block within easy walking distance of the West Oakland BART station. “There were blocks and blocks of this, wiped out. It’s just so dumb, and I think that’s always been my feeling about these big technological systems. I’m so amazed at how well they function, how beautiful they are up close. And then I’m always so disappointed that we don’t use them rationally, make them work for the benefit of all.”

Want more thoughtful reporting on infrastructure, globalization, and the cities we live in? Join Scope of Work as a paid subscriber today.

Like many people who live in New York, my understanding of urban life in America is admittedly focused on its oldest, largest, and most dense city. But the first city I really fell in love with was San Francisco, where my mom had grown up and which my family visited more or less annually when I was a kid. When I lived in the greater Bay Area, during and then after college, I passed through Oakland plenty of times—and yet it remained mostly amorphous, something tacked onto the place (San Francisco) that I romanticized so much. I can remember visiting someone on Alameda on at least one occasion, and I’ve driven the 880 dozens of times, and I have a distinct memory of being stuck in a train for hours in the East Bay for seemingly no reason. But I never really learned where Oakland started and stopped, and on the occasions when I knew someone who lived there, they were usually recent transplants.

I related this to Alexis, and he tried to explain how living in Oakland had shaped his understanding of the broader Bay Area. “On this side of the bay we have the big highways, we have the port, we have a lot of the backend infrastructure. It tunes people to think in a slightly different way than if you’re living in North Beach, or even the Mission.” We had driven north up the Mandela Parkway, then west towards the now-shuttered 16th Street train station, and were looping back on 14th Street towards downtown Oakland. “The crosswinds of development here are pretty intense for people,” Alexis remarked. “The financialization... the shear of it is pretty incredible.” Around Jefferson Street, I began to notice storefront after empty storefront: newly-constructed mid-rise buildings, their ground floor windows filled with colorful posters advertising their immediate availability for retail or restaurant use. “Work from home really took hold here,” Alexis told me. “I’m not sure I have a moral opinion about it, but I am worried that there’s been a structural change to the city. It’s hard to know if the density bonuses of a city can be maintained without in-person office work.”

This was a considerably gloomier perspective than I’ve had over the past few years, as New York’s street life has largely rebounded from the pandemic. Alexis continued: “Oh, it’s real here. In ways that are almost spooky, Oakland ends up concentrating so many of the problems of the Bay Area. If something awesome is happening in San Francisco—the weather, or the creativity of the population—Oakland is concentrating that same stuff. Like, there’s some cool anarchist types in San Francisco? We have cooler, more anarchist types. But if San Francisco is having a problem, we’re having that problem a little bit worse too.”

We meandered around downtown for a little while, then headed east on Grand Avenue. Lake Merritt, sparkling in the February sun, was to our right; on our left I noticed more unoccupied retail space. I asked about Alexis’ personal shopping habits, noting the multiple anecdotes in The Pacific Circuit which involve a crosstown errand, taken by bike and resulting in a meditative kind of reverie. He, in turn, described the feeling of going to a nationwide pharmacy and needing to press the customer service button just to get a tube of toothpaste. He described life in Oakland like a system that’s slightly out-of-balance. “It’s almost like there’s some nutrient that’s way too high in the mix, and you’re just waiting for some life form to figure out how to use it as an energy source.”

Our official tour was over; the part of West Oakland that The Pacific Circuit focuses on has a landmass of under two square miles, and we had traversed more or less all of it. Since its cultural institutions have either been shuttered or reduced to selling day-old coffee cake (a confection which Alexis dutifully purchased when he visited Revolution Cafe in a scene set late in The Pacific Circuit), we continued past Lake Merritt, parked, and got out of the car to sit down somewhere. “You should take your bag with you,” Alexis said offhandedly, reminding me of another scene in The Pacific Circuit in which he says “a small prayer” that his car’s windows will be intact when he returns. I was mildly surprised but took the suggestion, and we strolled down the block to a natural wine shop, where he ordered a glass of mineraly white and I got a bottle of ginger-lemonade kombucha.

I spent much of my young adulthood orienting myself towards San Francisco, and it still surprises me a little bit that I didn’t move there immediately upon graduating from college. Having grown up in eastern Long Island, San Francisco seemed distinctive, alluring, and totally different than New York. But Alexis sees the city from a broader perspective, and one that strikes me now as more accurate than my own. “San Francisco is California’s entry into the global archipelago,” he said. “The particular feature that might have differentiated it is this kind of street cosmopolitanism: Because it was a port city, it had all these people who were working class but extremely tolerant, and able to work across all these different cultures. These guys—their workplaces were the ships from all over the world, and their partners were drawn from all over the US, and on top of that they had all these interface points between the Italians in North Beach, and the Chinese people in Chinatown, and the yuppies in the Marina. That creates a totally different working-class sensibility than you find elsewhere, and I think containerization is one of the things that killed it.” This happened, as Alexis writes in The Pacific Circuit, because containerization required the building of new, more expansive ports. The potential of trans-Pacific trade was “too great for San Francisco. The only way that the levels of trade between a rising Asia and a dominant America could reach their potential heights would be the development of Oakland as a port.” And the development of Oakland as a port meant the loss of San Francisco’s tolerant, working class dockside labor.

This might seem a far-out claim to make: that containerization, a method of efficiently moving goods around, eroded the cosmopolitan sensibilities that defined mid-twentieth-century working-class life in San Francisco. But I do know that as soon as I was old enough to decide where I wanted to live, I found that San Francisco wasn’t quite the place that my mom, who left the city in 1981 and died in 1996, had shown me. San Francisco’s housing price index more than doubled between the year she moved away from the city and the year she died. By the time I got to college, in 2001, it had nearly doubled again, and it doubled a third time by 2017, when my first kid was born. Since 1975, the earliest year that the St. Louis Fed has data on, San Francisco’s housing price index has increased twenty-seven fold.

Meanwhile Oakland has, for better and for worse, remained significantly easier on working-class families. That is, working-class white and Asian families, and especially ones who were moving into neighborhoods like West Oakland, where property values had been depressed for decades by redlining—and by all of the negative externalities associated with living adjacent to one of the busiest container ports in North America. Alexis lays this history out in detail in The Pacific Circuit, through both aggregate statistics and through years of personal relationships with the people who live there. While his reporting resulted in more than a few heartbreaking stories, the accounting he gives is empathetic and nuanced; he refers to “administrative evil” at a few points in the book, but does not go so far as to include a villain. “The basic idea was that we wanted Asian economies to be tied to us,” Alexis told me. “We wanted access to their consumer markets, and we wanted access to their labor. This system got built, and it got built for particular reasons and on the backs of particular people. It’s had both positive and negative outcomes; the negative ones have been located in really specific places, but maybe one step up, at a regional level, you see that actually, it’s kind of been awesome for the Bay Area.”

Throughout our conversation, Alexis was clear about how much he cares about the city he lives in. His voice strained with endearment when he told me that he “has always felt more at home in Oakland than anywhere else.” I also got the sense that he genuinely appreciates the positive aspects of the globalized world that we live in today. He wears a decidedly cosmopolitan air, and on multiple occasions he expressed his engagement with and comfort in the conveniences—and the societal traits—that were brought on by containerized shipping, a strong dollar, and a Bay Area economy based on venture-scale returns on investment. But The Pacific Circuit looks hard at the complexities that these systems have resulted in, and the often painfully negative consequences that they’ve had for (among other people) the residents of West Oakland.

After having lived back on the East Coast since early 2008, it sometimes feels as if I never resided in California at all. So much of my time there seems to me now as a dream, my memories filtered through years of grappling with my own relationship with San Francisco, and its place within Californian culture, and the way that California has pulled on and been pulled around by the rest of American history. Which is to say that I’ve struggled to understand my time there. For that matter, the Bay Area has struggled a fair amount too. The economy collapsed shortly after I left, and about a year later Uber was founded (Alexis writes he isn’t “interested in Uber per se,” then goes on to note that the company’s worldview implies that “solidarity is an illusion” and “everything is transactional”). In the time since I left the state, San Francisco’s homeless population has increased by more than forty percent; California now has fifty percent of the country’s unsheltered homeless population. “We’ve pulled all of these different threads out of what was a very successful mid-century American society,” Alexis said as I sipped the last of my kombucha. “At times, while writing this book, I felt like I was describing a very high-stakes game of Jenga, where you’re asking, ‘What if we take this thing out, what if we take that thing out? What if we keep attenuating the city along all these different dimensions?’ And I just want to know, who’s going to be there to knit things back together?”

Like the rest of the country, Oakland’s Jenga tower is still a bit wobbly from the blocks that were pulled out of it in recent decades. And while Alexis introduces us to a number of admirable—if adversarial—characters in The Pacific Circuit, it’s fairly clear that the city will need new protagonists in the decades to come. I’ve never really known what to expect from the Bay Area; I suppose I’m too stuck reminiscing about what it must have been like when my mom lived there. But I, for one, am rooting for whoever its next protagonists might be—and Alexis Madrigal is high on my list of contenders.

The Pacific Circuit: A Globalized Account of the Battle for the Soul of an American City will be published this Monday, 2025-03-18.

Scope of Work is supported by readers like you. If you find this writing valuable, consider upgrading to a paid membership.