As Canadian engineering students near graduation, their days are filled with planning and executing elaborate pranks, hosting parties, and attending a secret ritual where they speak a solemn oath and receive a ring they’re meant to wear for life. The last bit is admittedly kind of bizarre, but I promise it is not a cult initiation; rather, it is a ceremony to mark the responsibility inherent in their chosen vocation. While the details of the ritual are not meant to be shared, certain aspects are common knowledge. For example, the oath that participants recite. It begins:

I, in the presence of these my betters and my equals in my Calling, bind myself upon my Honour and Cold Iron…

This ceremony is the Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer, which implores graduates to uphold ethical conduct. The tradition dates back to 1925, and is, allegedly, solemn and full of symbolism (to convey this gravity, everything associated with the Ritual is generally capitalized – a convention I follow in this piece). The only guests allowed are other engineers who’ve been through the Ritual, and while the ceremony isn’t exactly secret, it is decidedly private. At the end, the oath is recited, and participants are proffered their Iron Ring, a faceted (now stainless steel) ring meant to symbolize the responsibility inherent in their chosen vocation.

The tradition was initiated by mining engineer and educator Herbert Haultain in 1923. On a whim, he sent a request to Rudyard Kipling (author of The Jungle Book, and one of the most famous writers of the time), to create a ceremony that would bind together young engineers. Haultain tapped Kipling because his work was steeped in admiration for engineering; his writing demonstrated both knowledge and respect for the vocation. It was a pretty bold move, akin to me cold emailing Margaret Atwood and asking for advice on playing the recorder. Kipling wrote back just two weeks later with a package that outlined the entire Ritual.

The ritual also includes several of Kipling’s poems, which speak to humility and sacrifice. I find Hymn of Breaking Strain the most poignant:

The careful text-books measure

(Let all who build beware!)

The load, the shock, the pressure

Material can bear.

So, when the buckled girder

Lets down the grinding span,

The blame of loss, or murder,

Is laid upon the man.

Not on the Stuff—the Man!

The poem grapples with the fact that technical knowledge alone will not produce infallible structures – and if a structure fails, the individual engineers who built it must shoulder the blame. Textbooks are not enough to guide us, we need humility. It’s a powerful message to close out one’s education: say goodbye to case studies and hello to real world problems.

SPONSORED.

The Open Hardware Summit is accepting proposals for talks, workshops, and exhibitions until 2023-12-17. The summit will be held in Montreal, 2024-04-26 and 27. If cost to attend is a barrier, consider applying for the Summit Fellowship.

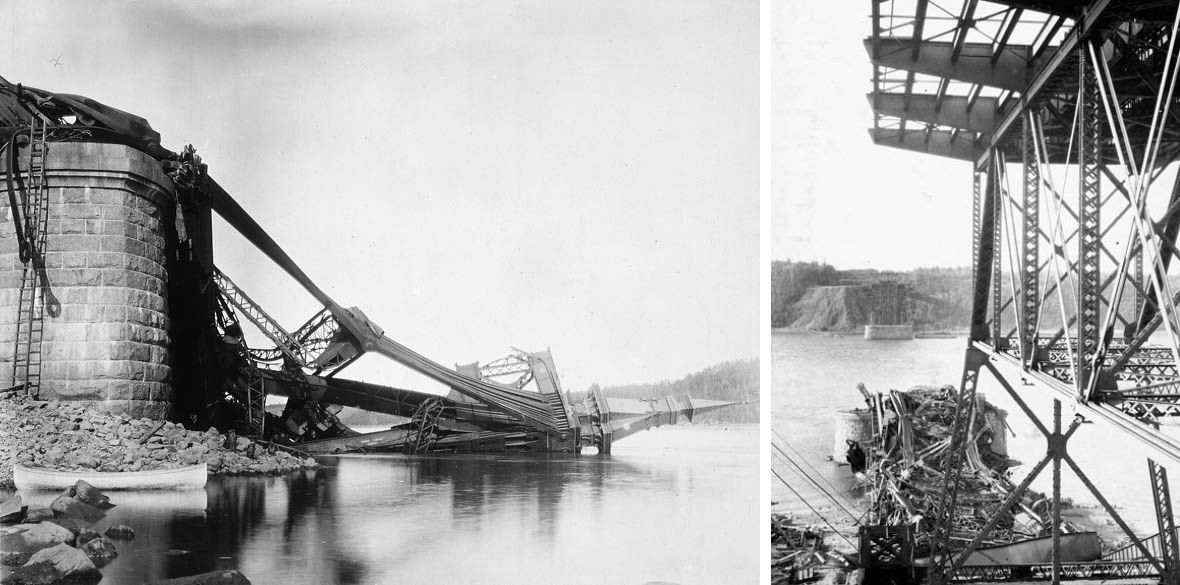

There is a long-standing myth that Iron Rings were originally forged from the wreckage of the Quebec Bridge, which collapsed in 1907 – a reminder of the ever-present risk of failure. The Quebec Bridge was meant to cross the St. Lawrence River, connecting Quebec City to the town of Levis. Instead, its superstructure collapsed into the river, killing 75 workers and leading Haultain to propose what became the Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer. As Dan Levert, author of On Cold Iron: A Story of Hubris and the 1907 Quebec Bridge Collapse, explains:

The Obligation taken by the engineering graduate during the Ceremony acknowledges one’s own assured failures and derelictions; it recognizes human frailty and teaches humility. There was no trace of humility in any of the senior engineers involved with the design of the Quebec bridge. Their arrogance and absolute confidence in their work prevented them from realizing what the workers building the bridge already knew: that the bridge was failing under its own weight.

The bridge’s collapse had left the public reeling, with Engineering News calling it “the greatest engineering disaster” and “a peculiarly heavy blow to the engineering profession.” While the bridge is in fact submerged in the St. Lawrence River, and not donned by young engineers, Canadian universities still connect the disaster to the Obligation and the lesson it’s meant to impart.

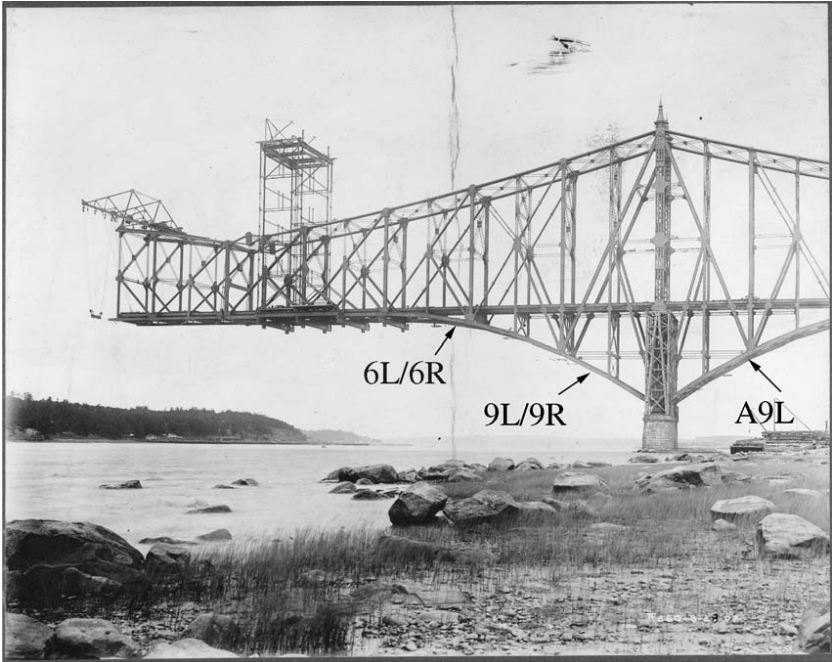

The bridge was essentially designed to fail. The design included massive technical oversights: the compression members were underbuilt, the bridge’s dead load was underestimated, and at the very beginning of planning, the consulting engineer had replaced standard bridge specifications with a set that allowed the steel to be stressed beyond usual limits. All of this meant that during construction one of the compression members, chord A9L, bent under the stress and eventually failed completely.

A public inquiry laid the blame on the bridge’s chief design engineer and a consulting engineer named Theodore Cooper; it concluded that “the failure cannot be attributed directly to any cause other than errors in judgment on the part of these two engineers.” Neither faced legal or financial consequences for the deaths of 75 people.

While only two people were blamed, other mistakes were certainly made. Engineers at the Department of Railways and Canals, who oversaw the project on the government side, could have conducted peer review on Cooper’s specifications – but instead they rubber stamped them. The construction firm could have physically tested the bridge’s components, but they deemed the chords too large for their test equipment and decided to proceed anyway. The dead load could have been carefully calculated but it wasn’t common practice at the firm. Despite the fact this bridge was unprecedented in its size, none of the firm’s staff thought to change the procedure and rerun weight calculations before fabrication. Finally, when the chords began to buckle and it was apparent that the bridge would fall, the engineers on-site could have accepted what was plainly true and asked the workers to get off the structure. The entire project was littered with mistakes and oversights – but buoyed by a belief that success was inevitable.

The oath that young engineers now recite is a warning against the kind of hubris that plagued the Quebec Bridge project, and the lackadaisical approach to safety that cost so many their lives. As Kipling writes, “Let all who build beware!” But the Ritual is also a reminder that no one is alone with this heavy responsibility. When asked what her Iron Ring means to her, my friend Tessa replied: “I especially like the emphasis on community; that you're returning not only to the fact that you took an oath, but that you did it with other people, and that thinking of them is part of what should guide you in taking ethical actions.” Another friend, Heather, shared a similar sentiment: “It’s building on years and years and years of commitment from other engineers to take pride in their work, to consider their place in society, and to strive to make the world a better place to the best of their abilities.”

Engineers are not uniquely obligated to do good and ethical work. But the Iron Ring has proved an enduring symbol of responsibility. It’s to be worn on the pinky finger of your working hand, so it clinks softly against your desk or workpiece throughout the day, reminding you of your Obligation as an engineer.

SCOPE CREEP.

While everyone I talked to for this piece was happy to participate in the Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer, there was one overwhelming piece of criticism: the ceremony is very Christian. Kipling’s poems are full of Christian imagery and associated patriarchal values. Deb Chachra has gently critiqued the Ritual and called for a more expansive idea of ethical conduct. Despite this legacy, the Ritual and the Iron Ring remain a meaningful endeavor. Heather again, explains,

While I do fundamentally disagree with the way some of the wording, and some of the history behind it and that it was written by a problematic man, I think the importance of the ring is better taken as what you personally make of it; like a lot of symbols, the importance is what meaning you place on it and how you interpret it, not just what everyone else makes of it.

The Corporation of the Seven Wardens, the spookily named organization that handles the Ritual, has evidently heard the same feedback. The Ritual is being modified to make it “meaningful and inclusive for all candidates” and new poems are being commissioned. Many universities are even moving away from private ceremonies, so participants can invite friends and families to observe. The Hippocratic Oath has also been updated periodically to reflect the times; the first was sworn to “Apollo the physician, by Aesculapius, Hygeia, and Panacea.”

FURTHER READING.

For more on the Quebec Bridge collapse, see this case study, this paper, and this book.

More details on the Ritual can be found on the Seven Wardens website, and of course on Wikipedia. To learn about Retooling the Ring, an organization that pushed for reforms to the Ritual, see this interview and this academic article.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks to Tessa, Heather, Eric, my dad Steve, and a smattering of other people I’ve bugged over the years for talking to me about your experiences – I hope I captured at least some of the mystery and grandeur of the Ritual.

Love, Hillary

p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here’s what we’re doing about it.