Here it comes! It's Scope Creep, and it's like a coil of rope that's been slipping through my fingers for the past couple of weeks. Every so often, I feel a knot. If I have time, I try to untie it, or at least turn it over in my hand to better understand how it's tied. Then I take the parts that I understand, and I put them down here.

Today's Scope Creep clocks in at just over twenty-five hundred words, and is the first free issue of SOW since 2025-02-03. But some knots take longer to untangle: While you've been waiting for this issue, paid readers have received an additional four thousand words of topologically complex Scope Creep. Upgrade today, and watch over my shoulder as I work through the knots I come across.

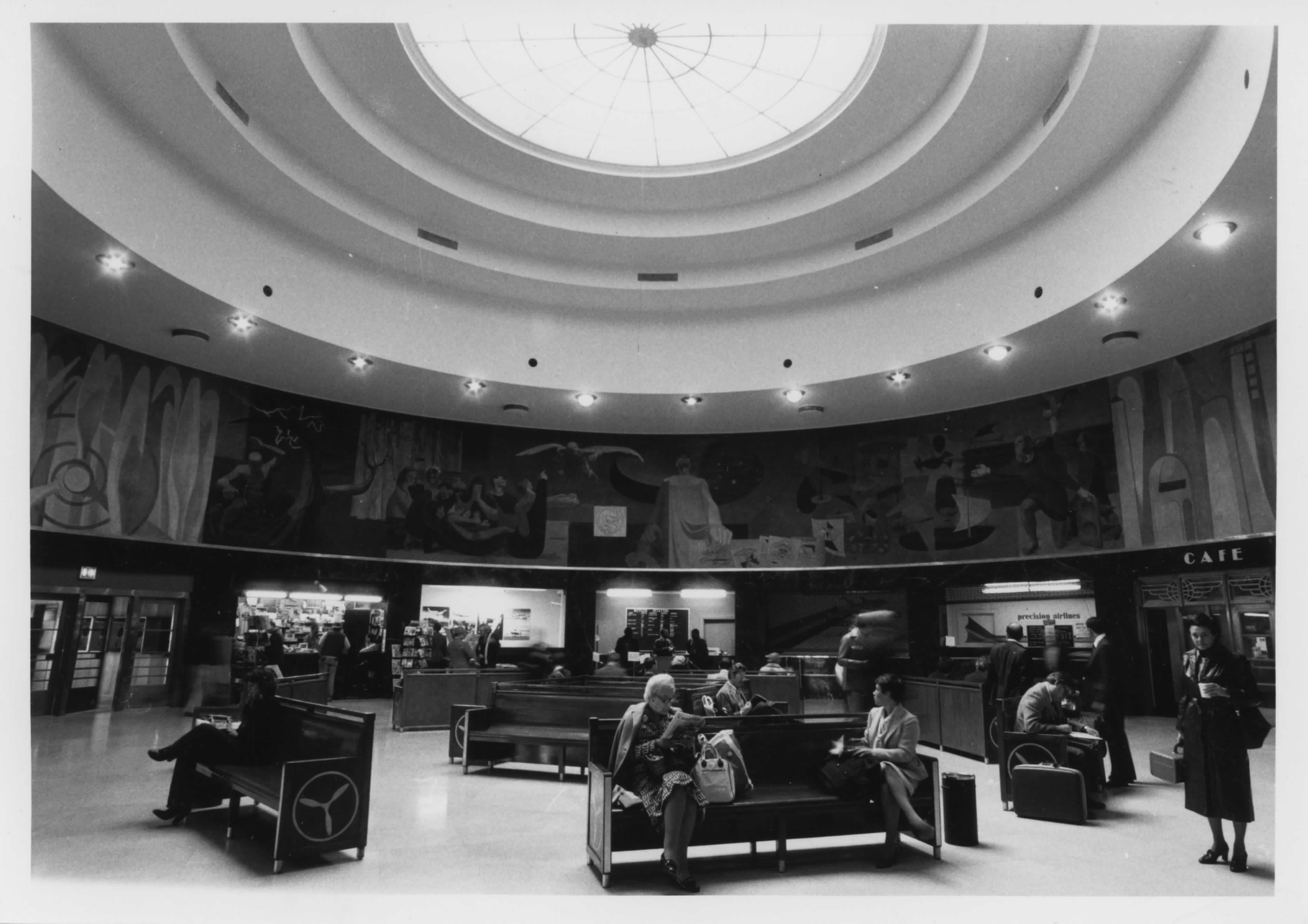

Let's start at an airport. Last week I reopened a draft in which I mentioned the rotunda at Laguardia's Marine Air Terminal. In the piece, I described the Marine Air Terminal as my favorite airport, "a friendlier terminal than anything at LAX, and less self-serious than Eero Saarinen’s TWA Flight Center across town at JFK." I then went on to describe the rotunda's mural, and in particular its depiction of a still-ascendent Icarus (one of three that appear in the mural) with "the sun tucked benevolently over his right shoulder as if its only purpose was to warm his back."

While I edited the draft, I spent a minute googling the mural and this particular portrayal of Icarus, which you can see in closer detail here. The Marine Air terminal is supposedly the Works Progress Administration's largest project, and its mural is supposedly the largest one the WPA ever commissioned—though in my memory the (really stunning) murals at Coit Tower loom larger. According to Sabiha and Geoffrey Arend (who calls himself "the acknowledged dean of air cargo publishers"), the mural was covered up in 1952 by the Port Authority for fears that it carried communist undertones. It then sat under layers of paint until about 1980, when it was landmarked and painstakingly unearthed. According to the dean of air cargo publishers, "The men who restored the mural sat over a weekend in my office, smoking dope and must have been higher than the flag on July 4th as they worked."

In 1982, the Marine Air Terminal was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In its nomination form, the terminal's owner is listed (the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey) as well as its acreage (under an acre) and location (the Central Park Quadrangle). The building's boundaries are shown on a site map (page 7), and a USGS Quadrangle map is also included (page 17), with the Marine Air Terminal marked. At the top edge of the Central Park Quadrangle is Inwood, where I went to visit the MTA's 207th Street shop with Christopher Payne. The Quadrangle map is detailed enough to show the structure we visited, and PS 98 across the street, and a fire station a few blocks away. But you'd be out of luck if you wanted to know who owned a particular parcel of land in Inwood. For that you'd need a cadaster—a document that lists, or shows on a map, which people own what land in a particular area. If a modern cadaster of Inwood exists, I can't find it, but this 1905 cadastral map shows property ownership for much of the land at the south end of Inwood Hill Park.

In the United States, the Bureau of Land Management maintains a cadastral survey of "all federal interest and Indian lands." According to the BLM's Manual of Surveying Instructions, "Since the Land Ordinance of 1785, it has been the continuous policy of the United States that land shall not leave Federal ownership until it has first been surveyed, and an approved plat of survey has been filed." This means that any land that was homesteaded, sold, or transferred to a private party by the Federal government was surveyed first; the BLM says that thirty states, which it calls "public domain states," were surveyed under this system. "With very few exceptions all chains of title to privately owned land in those 30 States trace back to a Federal land patent or other grant."

This does not mean that cadastral maps exist for the entire Western United States. If they did, they would certainly be useful (cadasters can help prevent title piracy, which is explained in this recent Planet Money episode), but as described by James C. Scott in Seeing Like a State, cadasters can also be used by governments to assess, tax, and control their citizens. A cadaster is an example of "the administrative ordering of nature and society...[they undergird] the concept of citizenship and the provision of social welfare just as they might undergird a policy of rounding up undesirable minorities." Scott goes on to explain the concept of high modernism, which emerged in the mid-twentieth-century and which he describes as "a strong, one might even say muscle-bound, version of the self-confidence about scientific and technical progress, the expansion of production, the growing satisfaction of human needs, the mastery of nature (including human nature), and, above all, the rational design of social order commensurate with the scientific understanding of natural laws."

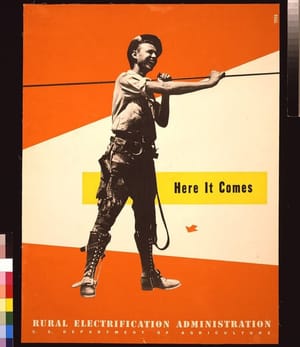

Once I was introduced to high modernism, I began seeing it everywhere; it helped that I happened to visit the Museum of Modern Art, where I saw Frank Lloyd Wright's model for a highly ordered prairie city called Broadacre, as well as the stunning posters that Lester Beall made for the Rural Electrification Administration. As Scott explains, high modernism is not defined by or confined to a particular political ideology:

One can identify a high-modernist utopianism of the right, of which Nazism is surely the diagnostic example. The massive social engineering under apartheid in South Africa, the modernization plans of the Shah of Iran, villagization in Vietnam, and huge late-colonial development schemes (for example, the Gezira scheme in the Sudan) could be considered under this rubric. And yet there is no denying that much of the massive, state-enforced social engineering of the twentieth century has been the work of progressive, revolutionary elites.

High modernism has a complicated legacy; what other political philosophy can claim to have been used by the likes of Lenin, Le Corbusier, and Robert Moses? We can also see traces of high modernism in more recent (and no less controversial) efforts, like the Obama-era US Digital Service (now DOGE 🫥) and NYC's congestion pricing program (🥹). Whatever your broader goals, high modernism offers to impose order on otherwise intractable systems—sometimes elegantly, sometimes tragically.

Here's a not-so-intractable system, which humans also attempt to impose order upon: The growth patterns of rhubarb, the fruitiest of all vegetables. This is done most famously in a region of Yorkshire called the Rhubarb Triangle. It used to be bigger, but these days you could drive the perimeter of the Rhubarb Triangle in a couple of hours. In the Rhubarb Triangle, around this time of year, rhubarb is grown in heated, darkened sheds, a process called forcing.

This is how it works: During the winter, rhubarb stores energy in an underground organ called a "crown." When it gets warm, the crown will send out stalks, and if the stalks see sunlight then they produce oxalic acid (which is the source of rhubarb's tart flavor, and also the active ingredient in Bar Keeper's Friend). But if there's no light available, the stalks will just grow and grow, depleting the crown's energy stores and resulting in sweeter stalks. To make sure that the forced rhubarb's tartness is turned all the way down, it's harvested only by candlelight.

Before World War II, forced rhubarb was one of the few sweet winter treats you could get in England. This made it incredibly popular, so much so that there was a dedicated rhubarb train that ran every night from west Yorkshire to London during the rhubarb forcing season. "Up to 200 tons of rhubarb sent by up to 200 growers was carried daily at the peak of production before 1939." But after the war the availability of imported fresh fruit improved, and forced rhubarb production declined. Here's an interview with one current-day farmer in the Rhubarb Triangle, whose boxes I happened to come across outside of a bakery a few weeks ago. Incredibly, some of his crowns date back from before the war, when rhubarb forcing was big business.

Sometimes I need to remind myself that there was a period of history when the trains worked well, and roads barely existed. In the US, the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. It took an additional forty-four years for automobile enthusiasts to create the first transcontinental road: the Lincoln Highway, the route for which was built by the (privately organized) Lincoln Highway Association (LHA) in 1913. Even then, the Lincoln Highway was almost completely unpaved, and driving it was "something of a sporting proposition," often demanding that the driver get out and push their car through deep mud. From a Federal Highway Administration history:

In 1920, the LHA decided to develop a model section of road that would be adequate not only for current traffic but for highway transportation over the following 2 decades. The LHA assembled 17 of the country's foremost highway experts for meetings in December 1920 and February 1921 to decide design details of the Ideal Section. They agreed on such features as:

- A 110-foot right-of-way;

- A 40-foot wide concrete pavement 10 inches thick (maximum loads of 8,000 pounds per wheel were the basis for the pavement design);

- Minimum radius for curves of 1,000 feet, with guardrail at all embankments;

- Curves superelevated (i.e., banked) for a speed of 35 miles per hour;

- No grade crossings or advertising signs; and

- A footpath for pedestrians.

The Ideal Section was built during 1922 and 1923, with funds from the Federal-aid highway program, the State highway agency, and Lake County as well as a $130,000 contribution by the United States Rubber Company

Here's a cheesy but pretty informative video about the Ideal Section of the Lincoln Highway, which was built between Dyer and Schererville, Indiana. If anyone out there happens to live near Dyer or Schererville, Indiana, please let me know; I'd love to know just how ideal the Ideal Section looks today.

SCOPE CREEP.

- Well, here's an industrial catastrophe that I wasn't previously aware of: In 1984, a Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, India leaked forty tons of methyl isocyanate gas. The methyl isocyanate killed something like sixteen thousand people, and injured something like half a million.

- Apparently the standard industry size for large blocks of clear ice (for ice sculptures, fancy cocktails, etc.) is 41" x 20" x 10". To make ice that's really clear, freeze it in one direction only (bottom-up is standard for ice machines like this one, though clear pond and river ice freezes top-down) and keep the water circulating, to remove bubbles, while it freezes.

- Worcester v. Georgia was decided by the Supreme Court in 1832. Its details are complicated, but at a high level the Court determined that the Cherokee were essentially an independent nation. As a result, the State of Georgia couldn't decide who could or could not reside within the Cherokee nation. In the end the ruling was enforced, and Samuel Worcester (who had been arrested and jailed by the State of Georgia for residing within the Cherokee nation) was freed. But it took a while, and sparked a few pretty big constitutional crises in the meantime—including the (apparently apocryphal) quote, from President Andrew Jackson: "[Chief Justice] John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" Marshall didn't attempt to enforce it, and didn't explicitly ask Jackson to either. Eventually, Jackson opposed Georgia's attempts to nullify the court's decision... but it was hairy there for a minute.

- Also related (somewhat mysteriously!) to the draft that I've been working on: This excellent article on the history of tipping, from last year, which has really stuck with me and deserves your time.

- The SOW Reading Group is about two-thirds of the way through Building SimCity, and I'm looking forward to chatting with author Chaim Gingold on 2025-03-20. During one of our recent chats about the book, I went back and took a second look at La Tabla, a project Gingold made using projection mapping to create a flexible and playful multimedia work surface. It's a little hard to describe, so you should just check out the project's website and watch enough of the video to see the pinball machine demo—it's totally worth a minute of your time.

- I had the pleasure recently of re-reading On Geofoam, Anna & Kelly Pendergrast's feature article about the styrofoam that is used extensively in civil engineering and landscaping. Man, that piece is good!

- Garden snails' shells pretty much always grow in right-handed spirals; maybe one in forty thousand garden snails grow a left-handed spiral. Snail reproduction requires that their shells line up just right, and left-handed shells do not line well with right-handed shells. As a result, snails with left-handed shells can't procreate unless they find a (very rare) mate. But recently, because of the internet, a couple of left-handed garden snails prevailed. And wow, what a process:

The way snails mate is "fantastically bizarre," Davison says. The carnal act is known as 'traumatic insemination,' and copulation kicks off by mutually stabbing each other with 'love darts' — tiny calcium spears that transfer a hormone. Snails are simultaneous hermaphrodites, he says, meaning that they are both male and female at the same time and will 'reciprocally fertilize each other' and ultimately each produce offspring.

In a further twist, snails can reproduce on their own because they are hermaphrodites. But Davison says this happens 'very rarely but they'd much prefer to mate with another snail.' Inbreeding, he notes, is 'generally not a good strategy.'

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks also to Alessandra for helping source links this week.

Love, Spencer