Yesterday I received notes back on a profile that I spent much of the past year thinking about and (eventually) writing; I'm excited, and slightly nervous, to share it with you in the new year.

Over the next two weeks I'll be experimenting a bit with my writing and publication schedule. Instead of publishing my work to the free newsletter, I'll be breaking it into postcard-sized chunks, which I'll (literally!) hand write and send to whichever paid readers have shared their addresses. These handwritten bits will then come together into a single Scope Creep issue, sent exclusively to paid subscribers on the first Friday in January. Paid subscribers can find a link to submit their addresses in the emailed version of this newsletter.

This seems like the perfect moment to remind you that Scope of Work became sponsor-free in 2024. This means that literally 100% of our revenue — and my income — now comes directly from readers like you. This change has been challenging, but it also allows for more honesty, better alignment to our readers' values, and a much more creative end product — all without having to think about ads, clicks, or our sponsors' sales cycles. Without sponsors, I can focus entirely on producing the kind of work that resonates most deeply with readers like you. I'm incredibly grateful to the ~700 paid subscribers who make possible everything we do. If you’d like to join them — and get a postcard, along with full access to today's newsletter — please upgrade to a paid subscription today.

SCOPE CREEP.

This was a fun one to write ;) There are threads everywhere; what a pleasure it is to let yourself find — and follow — them.

- My notes on… some number of books I’ve read recently. I’m planning to bring a few (paper) books with me on vacation next week: Munir Hachemi’s Living Things, Tim Krabbé’s The Rider, and Robert M. Levine’s Father of the Poor? Vargas and His Era. This last book has been on my shelf for some time. Its subject, former Brazilian president and dictator Getúlio Vargas, was as I understand it instrumental in setting the stage to Manaus’ ascendancy as a tax haven for multinational electronics firms looking to sell their wares within Brazil.

Vargas became “interim” president of Brazil in 1930, and ruled, drifting towards authoritarianism, for fifteen years. In 1945 he was ousted by the military, but in 1951 he won an actual election and became president again. His second term lasted three years. In 1954, there was an attempted assassination on an opposition leader; the opposition leader survived, but during the skirmish an Air Force Major was murdered. In the investigation that followed, Vargas’ bodyguard was implicated in the assassination attempt. The Brazilian military demanded Vargas’ resignation for the second time; he agreed to “go on leave,” then dramatically shot himself in the heart a few hours later.

But my interest in Father of the Poor is primarily about Vargas’ philosophy of economic development; as I understand it, it was his restrictionist policies that created the political will for the Manaus Free Trade Zone. As I wrote in the post above:

As of 2016, Brazil’s GDP was the 8th largest in the world – but it ranked 24th for both imports and exports. Brazil also had the fourth-highest tariffs of any WTO member in 2016, and the highest tariffs on capital goods of any G20 developing economy in 2015. But Manaus’s free trade zone, established in 1967, offers a range of financial and operational incentives that make it appealing to multinational companies. The free trade zone has in many ways been a success, but it is also dominated by multinational firms that have for the most part not invested in local supply chains.

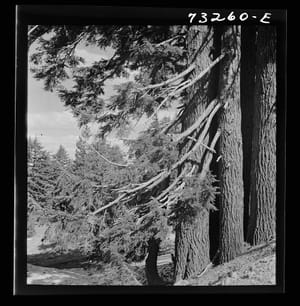

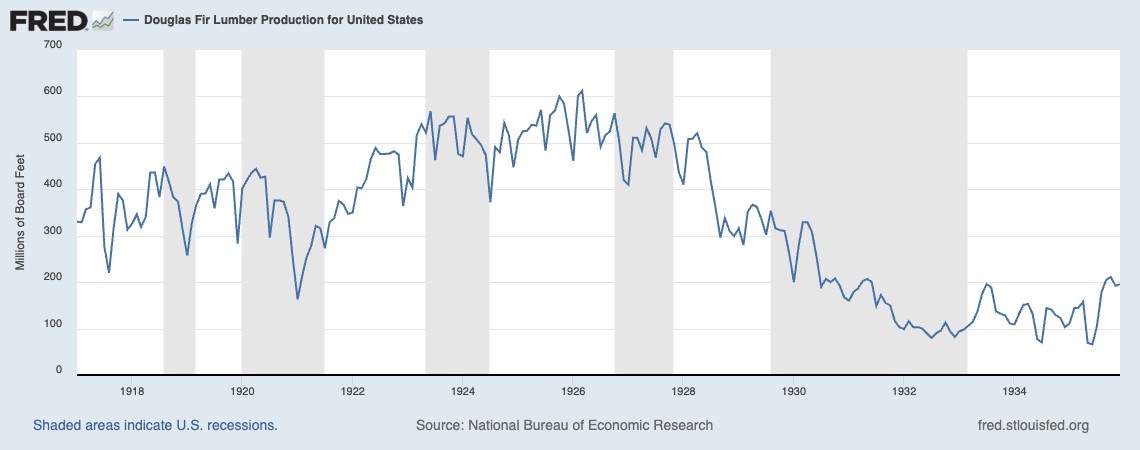

- On audio, I’m currently reading Murray Morgan’s The Last Wilderness: A History of the Olympic Peninsula. I am interested in it partly because of the development of the Olympic National Forest and Olympic National Park, which combined to preserve a remarkable amount of otherwise valuable natural resources. I’m also interested in the development of the aviation industry, which has such a big foothold in the Pacific Northwest partly because of the availability of strong, light timber on the Olympic Peninsula.

Here’s a factoid I learned from the first few chapters of The Last Wilderness: The term teamster initially meant someone who drove a team of animals, typically bulls to pull a heavy load. And here’s a wonderful description of Douglas fir:

Douglas fir, the dominant tree on the peninsula, has also been called Oregon pine, red pine, Puget Sound pine, Oregon spruce, red spruce, Douglas spruce, red fir, yellow fir, Oregon fir, and spruce fir. Its scientific name, Pseudotsuga taxifolia, is a compound of Greek, Japanese, and Latin, and means “false hemlock with foliage like yew.” David Douglas, the Scottish botanist and explorer who is honored by its popular name, described the tree in his field books as “one of the most striking and truly graceful objects in nature.” Then he added prophetically, “The wood may be found very useful for a variety of domestic purposes.”

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now