I think we had only been in Aberdeen for a couple of hours. Yes – we had landed in Aberdeen in the afternoon, and I had seen an ad for an offshore oil & gas company in the tiny airport, and basically as soon as we checked into our charming little hotel I had insisted that we go outside for a walk. It was evening by then and completely gray out, a condition that persisted basically around the clock until we left the country, but warm enough to walk around in light jackets. Aberdeen is an oil and gas town at the northeast corner of Scotland. And we were there working for an oil and gas company.

I think so many things about that now, but at the time I saw it as an incredible opportunity to be paid to poke around inside a really big company and then tell its executives how I thought it worked. If I had the opportunity to do it again I probably would. Plus we got to walk around Aberdeen, and poke at things there, too.

If the EXIF data on my photos is accurate then we had been walking for about an hour, first through Castlegate and then down to the Regent Quay. At that point I would have gestured out towards the North Pier and made some effort to continue the conversation, and the walking. The scenery is pretty utilitarian there, and we wouldn’t get to Footdee (which is kind of cute and has been inhabited since 1398) for another forty-five minutes. We must have been exhausted; after arriving in London on a redeye the previous day, I believe I had taken a nap on the floor of our client’s office. But now we were being squeezed between the internal organs of the world: a working-class bar, a series of obscure oilfield services offices, a pile of ship anchors, each the size of a small house. It was there, almost to the pier, that we found ourselves walking into an ungated dirt lot, our jaws scraping the ground like snow plows. There couldn’t have been much to say; Jordan picked his rope; we documented the moment, then walked on.

PLANNING & STRATEGY.

Haas, which at between a thousand and fifteen hundred employees is probably the largest machine tool manufacturer in the US, released a small-footprint, high-speed drilling and tapping center, the DC-1, which looks a lot like the Fanuc Robodrill and the Brother Speedio (both of which are made by Japanese companies and reportedly start at $55-65k) and is priced to compete with offerings from Tormach (who don’t make a drill-tap center, but whose vertical CNCs start under $10k) and Syil (whose T5 drill-tap center starts at $46k).

I first became aware of machines like these because of their reported usage in Apple’s supply chain: With so many smaller-than-a-breadbox products being manufactured from extruded and machined aluminum, it has long been rumored that Apple has special relationships with Fanuc and Brother in particular. (In a recent conversation I had with an Apple engineer, they jokingly referred to the “infinite Robodrills” they had at their fingertips.) And indeed, if you look closely at the first CNC operation in Apple’s Making the Vision Pro video, you’ll see a machine that is similar (but not identical) to the one in Haas’ DC-1 demo video. On the (varyingly offensive) Practical Machinist forum thread about the DC-1, speculations abound as to the machine’s true origin: Perhaps, as Greg Koenig commented, it’s a white-labeled Chinese mill, assembled from a kit in Haas’ Oxnard factory; indeed, a label on the spindle of the DC-1 demo video does seem to indicate that it might be a rebranded SpeedCN machine. (I reached out to Haas to confirm where and how the DC-1 is made; the operator seemed to be guessing wildly as to who could answer my question; I left a voicemail and never heard back.) Koenig also points out that the Vision Pro’s frame’s second machining operation appears to be done on a JingDiao GRA100, a five-axis machining center which can be seen here applying a mirror finish to a piece of stainless steel.

See also: iFixIt’s Vision Pro teardown; NYC CNC’s 2017 tour of the Haas factory, and this meditative 2021 video, produced by Haas itself and devoid of dialog, of work being done at their Oxnard factory.

MAKING & MANUFACTURING.

Three things inspired by doing a really bad job painting the fingernails on my left hand last weekend:

- A decent infographic + explainer on the chemistry of nail polishes.

- An okay video of the ORLY nail polish factory in LA, and another one of the Zoya factory in Ohio.

- A 2015 Siggraph video which (pretty convincingly) simulates paint being smushed around by a brush.

MAINTENANCE, REPAIR & OPERATIONS.

My kitchen faucet has an integrated, retractable spray nozzle. To switch from a single aerated stream to a somewhat haphazard cluster of streamlets (that is, to spray), a small button on the back of the nozzle is pushed. To switch back to the single stream, the faucet is turned off and then back on again – a process which in ideal conditions allows the spray button to pop back out to stream mode. Ideal conditions have not, in my experience, held for long; every few months the spray button becomes stuck in the depressed position, which the manufacturer (whose name rhymes with bro-ey) suggests fixing by soaking in white vinegar. This takes at least a whole day, a period during which the faucet spits at you like an angry garden hose.

Vinegar is, according to Wikipedia, “the most easily manufactured mild acid.” Humans have been making it for at least five thousand years. Its invention may have been accidental: The acetic acid which characterizes vinegar is the result of bacterial fermentation of ethanol, which people have made in the form of wine, etc., since at least 6600 BCE; at around 3000 BCE some Babylonian date wine seems to have accidentally fermented into acetic acid. The manufacturing process for white vinegar today is boring enough that there are almost no videos of it on YouTube – although there are, of course, scores of would-be influencers who are excited to tell you why they started making their own vinegar (mostly made from fruit) at home.

If you were getting tired of this and wanted to clean your faucet more quickly, oxalic acid sits somewhere in that zone between “probably won't kill you” and “probably won't make your faucet stronger.” Commonly found in household cleaners like Bar Keepers Friend (which if you’re up to date on The Bear, you may know as “science, Jeff!”), oxalic acid is also the reason that we don’t eat rhubarb leaves, which contain high amounts of it. It is apparently effective at rust removal, but in my kitchen it’s used to break down the hard, sticky residues that form when fats are heated to high temperatures – especially on stainless steel pans, on which those residues look particularly unappealing. You could, I suppose, make oxalic acid at home, but the process looks... less easy than vinegar.

DISTRIBUTION & LOGISTICS.

The USDA employs almost a hundred thousand people, making it about the same size as Honeywell, Delta Airlines, and The Gap. They produce a lot of reports, which anyone can download in PDF format but which I hesitate to say that anyone could read; I certainly struggle to. Take, for instance, last week’s Avocado data from the New York Terminal Market report:

AVOCADOS: MARKET STEADY. cartons 2 layer DOMINICAN REPUBLIC OTHER GREENSKIN VARIETIES 14s 28.00-30.00 16s 28.00-30.00 18s 28.00-30.00 24s 22.00-24.00 MEXICO HASS 32s 50.00-52.00 occasional higher fine appearance 54.00-56.00 36s fine appearance 48.00-50.00 40s fine appearance 45.00-48.00 48s fair quality 33.00 34.00-36.00 fine appearance 42.00-44.00 60s fine appearance 34.00-36.00 cartons MEXICO HASS 70s fine appearance 36.00 14-5ct

Avocado prices have been remarkably stable over the past month. Total avocado imports from Mexico, however, surged by almost 40% (from ~55 to ~75 million pounds per week) in advance of Super Bowl Sunday. Like bananas, avocados are picked unripe and can be shipped, refrigerated, over long distances. After picking, they’re hydrocooled (video) to around 16°C and then refrigerated to 5-7°C, a temperature which allows them to remain fresh for weeks on end. But the really fun thing about avocado supply chains is that the fruit won’t ripen on the tree, and can be stored for months by simply leaving them where they grow.

INSPECTION, TESTING & ANALYSIS.

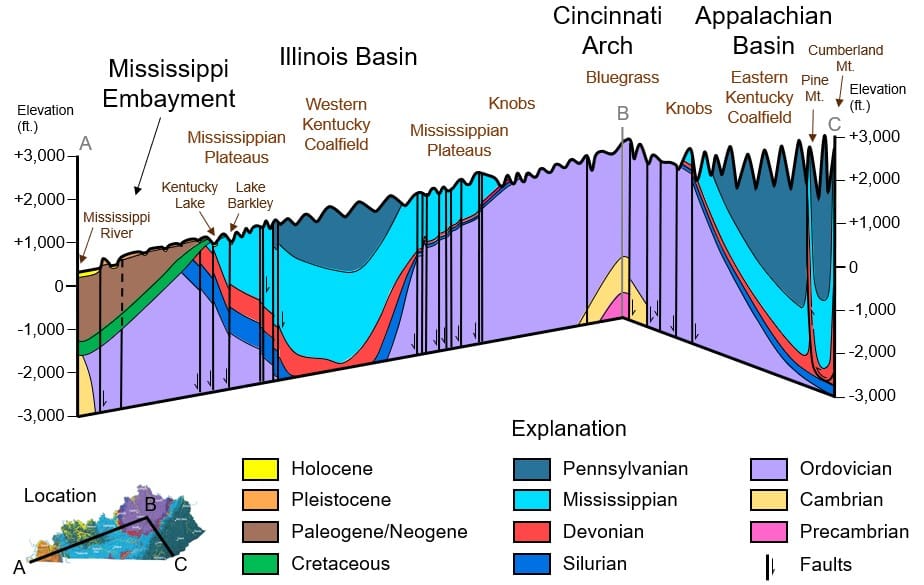

In the Southern United States, whiskey stills are often located on streams. It makes sense: Whiskey is mostly water, and the part that isn’t water still requires water to make, and if your still is right on top of a stream – a clean stream, and ideally one that’s fed from a naturally-filtered underground aquifer – then you can draw water right from that stream whenever you want. The water that’s drawn from a stream in this fashion is called branch water, I guess because a stream is to a river kind of like a branch is to a tree, and legend has it that some distilleries’ tasting rooms offer the same branch water to customers wanting to dilute their drinks down a little. Because these distilleries are located on the Cincinnati Arch, their branch water has been filtered through Ordovician limestone, leaving it devoid of iron and high in calcium and magnesium. Supposedly, this tastes good.

If you don’t live near a distillery, which is located on a stream, and which offers branch water to customers in their tasting room, then you can purchase bottled, Kentucky-sourced water which is naturally infused “with delicious hints of calcium and magnesium” by the limestone filtration process. Here is a silly taste test which in the end praises this product; here is an academic paper, based on “computer simulations of water-ethanol mixtures in the presence of guaiacol,” which explains how the flavor-enhancing compounds in whisky (and, presumably, American whiskey as well) are easier to taste when it’s diluted to a proof of 100 or lower.

Related: Here’s a highly detailed map of the geology of Kentucky, compiled over half a century from 7.5-minute USGS maps.

SCOPE CREEP.

One of my favorite bits, in the semi-comedic sense of the word, is that the word “bro” cannot be defined in objective demographic terms, its shape instead being formed by the relationship that the speaker has with a given subculture. “Bro” can be used in two main contexts: the sincere and the pejorative. In the sincere context, the speaker is indicating that they, and the person they’re calling “bro,” are both members of a particular subculture, e.g. “Nice Nirvana shirt, bro.” In the pejorative context the speaker identifies a third person as a member in a particular subculture and at the same time distances themselves from the same subculture, e.g. “That guy is a real tech bro.” Of course, “tech bro” refers to a relatively well-defined subculture; the phrase is almost an idiom unto itself. But it would be just as reasonable to speak of math bros, or knitting bros, or knot theory bros – just so long as the speaker doesn’t associate themselves with the group in question, and as long as the purported bro in question does.

Love, Spencer.

p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here's what we're doing about it