With 2023 drawing to a close, I have a New Year’s resolution: I will do more field reporting. This has been on my mind while reading one of the infrastructure-writing greats, John McPhee, who lovingly chronicles the lives of his subjects. In Uncommon Carriers, he rides along on a chemical hauling truck, a coal train, and a river barge, and reports back the details of the professional niches they travel within. One essay in the collection, which was also published in The New Yorker, starts with the logistics of storing and shipping live lobster in Nova Scotia. When an order is placed, the lobsters are packed into styrofoam containers and trucked nonstop to a warehouse adjacent to the UPS Worldport hub in Louisville. Here, “the hub sorts about a million packages a day, for the most part between 11 P.M. and 4 A.M. Your living lobster, checked in, goes off on a wild uphill and downhill looping circuitous ride and in eight or ten minutes comes out at the right plane.”

In another essay, McPhee reports from Port Revel, a facility where maritime professionals practice piloting on 1:25 scale vessels (see, for example, this man on a tiny “container ship”). He explains: “They are replicas of real and specific ships, to scale, with bulbous bows and working anchors.” Even the site of Port Revel, a placid French lake, was chosen purposefully as a light breeze is proportional to stiff ocean winds for these Lilliputian ships. While the concept of Port Revel seems silly at first blush, McPhee treats the endeavor with the utmost seriousness; he calls the training exercises “the Indianapolis 500 in geologic time.” In a replica of the Suez Canal, the little vessels battled against the bank effect, the same phenomenon that threw the Evergiven off course. While none of the vessels became quite so lodged into the banks, one captain swerved “all over the canal, hitting both sides.”

I appreciate the immediacy of McPhee’s writing; it feels like I am sitting right there in the cab of a truck. It’s a reminder that to do the work I want to do, I need to get out of my office and into the world. So in 2024, let’s explore canals, steel mills, and freight networks together. It’s time to dust off my steel-toed boots (and immediately get them dusty again).

This goal is really just a continuation of what I have already been doing for the past 9 years. My favorite pieces I’ve written at SOW are the ones based on experience and observation. While I read never-ending piles of background on the topics I cover, the ideas in them often only click when I find a way to go visit. For instance, in 2023 I read three books and dozens of reports about Hydro-Quebec, in the process learning about the political revolution that fueled the growth of a decarbonized electrical system in the 1960s. But while it’s one thing to read an academic account of the cultural significance of Hydro-Quebec, it’s another thing entirely to be immersed in a crowd of Quebecois singing a ballad about it.

I think the best piece I’ve written in this vein is Déneigement Montreal, a chronicle of the city’s complex snow removal operations. Montreal budgets nearly $180 million for snow removal annually, and employs 3,000 workers. Montreal doesn’t just plow snow – they cart it out of sight, and for one frigid morning, I followed these teams through the icy streets to gargantuan snow dumps. Standing at the bottom of Francon quarry, I watched trucks back up to a cliff and pour snow into 80-meter heaps. By the end of the season, the quarry stores about 4.8 million cubic meters of snow and ice. My guide, Philippe, remarked that the grandeur of the quarry always reminds him of Jurassic Park. Watching truck after truck fill up this massive pit, hidden in plain sight in suburban Montreal, the film’s soaring theme would have been an appropriate soundtrack.

What I like so much about the snow piece is that I got a window into the work lives of the people who are integral to this hidden system. My job is to interpret what is happening, chronicle it, and make sense of it so I can share with you the details of how a small portion of the world works. And it is a joy to invite you behind the scenes alongside me.

So, you’re invited to learn about Panama with me next year. I’ll be visiting in February, ostensibly on a vacation to see my in-laws. But instead of researching beaches, I’ve just been reading about the canal, chatting with the Panama Canal Authority, and scheming on how I might transit from ocean to ocean in a container ship. I’ve decided to add a week to the trip for research, reporting on the sights, sounds, and complexities of modern-day canal operations. It’s exciting – an adventure waiting to be lived, made sense of, and chronicled here in Scope of Work.

It’s a big step from traversing the infrastructure in my backyard; while the hydroelectric infrastructure in Quebec is important to much of the Northeast, the Panama Canal is important to the global economy. As a Council on Foreign Relations report explains, “Some thirteen to fourteen thousand ships pass through the canal each year, generating upward of $2 billion in revenue. The United States is the canal’s largest user; 40 percent of all U.S. container ships traverse it annually, carrying $270 billion in cargo.”

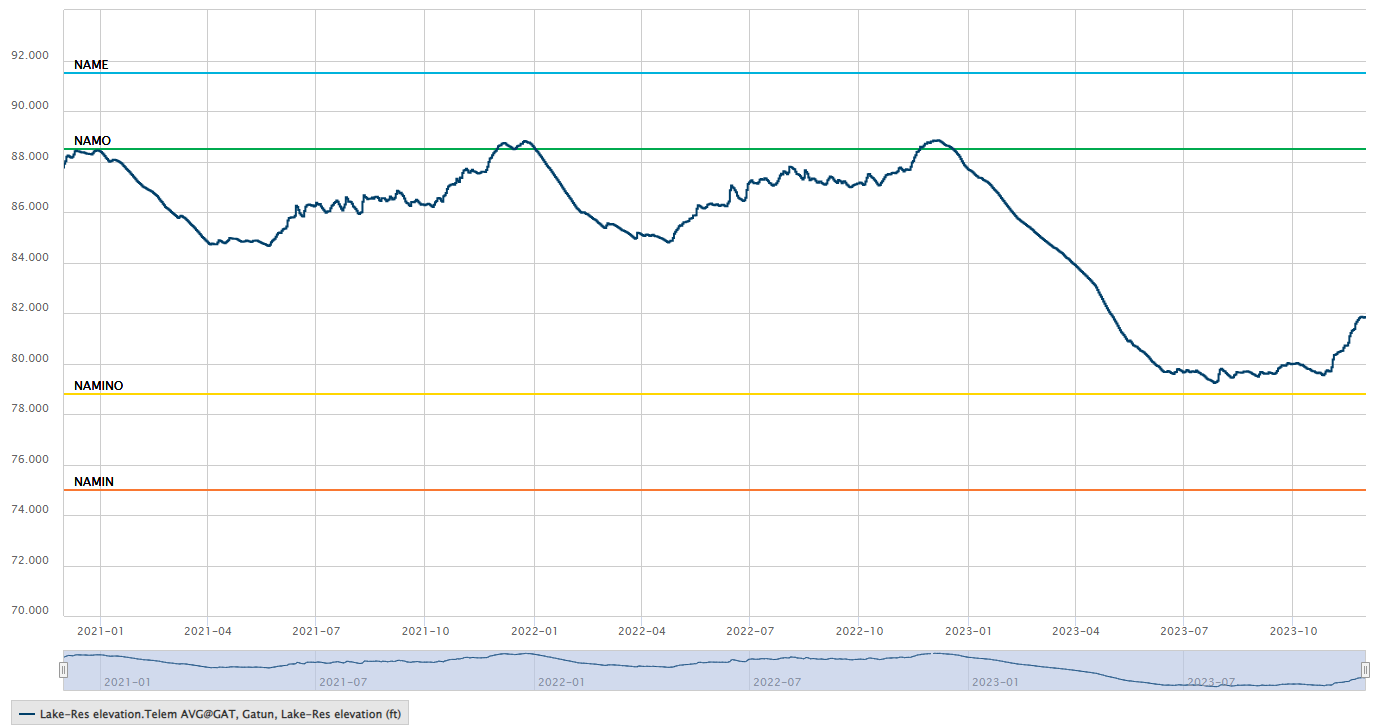

And 2024 will be a critical year for the canal: Panama is experiencing an extreme drought, putting canal operations at risk. This October was the driest in 73 years. By February, transits will be limited to 60% of peak capacity, and in the meantime, the canal authority is auctioning off access to the locks. The future of this artery of global trade is unclear.

To understand how the canal is affected by drought, you need to zoom out and look at its design. I had seen videos of ships moving through the canal’s locks – massive vessels nestled snugly into concrete basins – and initially assumed that the rest was similarly hemmed in. In fact, only the locks are cast in concrete; the rest of the passage is an artificially created, rainfed watershed that covers over five thousand square kilometers. This freshwater pours down into the locks on both the Pacific and Atlantic sides to move vessels up and down the 26-meter elevation. Each ship that crosses the canal flushes an average of 200,000,000 liters of fresh water out to sea, so each transit exasperates drought conditions.

In more human terms, “The passage of one ship is estimated to consume as much water as half a million Panamanians use in one day.” Nearly 58% of the water withdrawn from the watershed is used to operate the locks, 36% is used to generate electricity (for both canal operations and nearby communities), and 6% is used for drinking water.

The Panama Canal has been lauded as one of the most spectacular engineering projects of all time, but like all human creations, it exists in tenuous collaboration with nature. A lot is riding on the water level of this artificial watershed, both for Panama and for the rest of the world. Next year, I’ll be bringing you a deep dive into the history and future of this crucial path between two oceans and stories about what it means to those who work there.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks to Richard for recommending the McPhee book – you were right, it was the one with the tiny ships. Thanks to Andy for making some initial Panama introductions (and for helping all the critters in the rainforest).

Love, Hillary

p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here’s what we’re doing about it.