Until recently I lived in Montreal, Quebec, and while there were many things I admired about the city, what really grabbed my attention was the infrastructure that delivers its electricity. Quebec is electrified almost exclusively by hydropower and after exploring some of the dams closer to home, I ventured further afield, traveling 900 km to visit Manic-5. This massive dam is a significant part of Quebec’s unique grid.

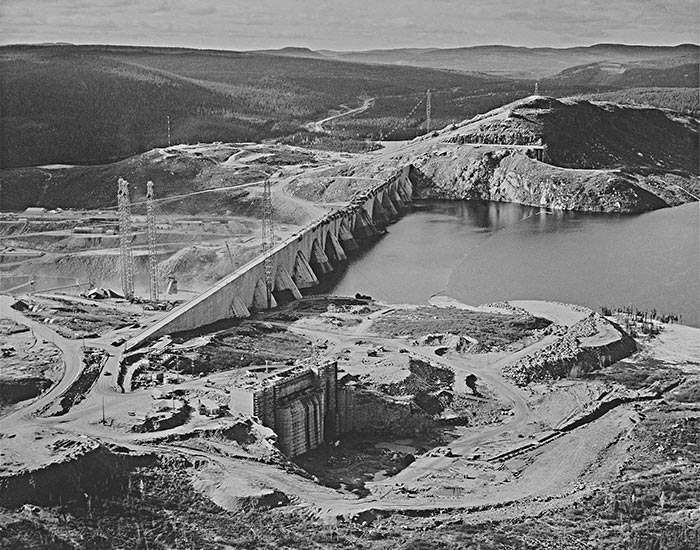

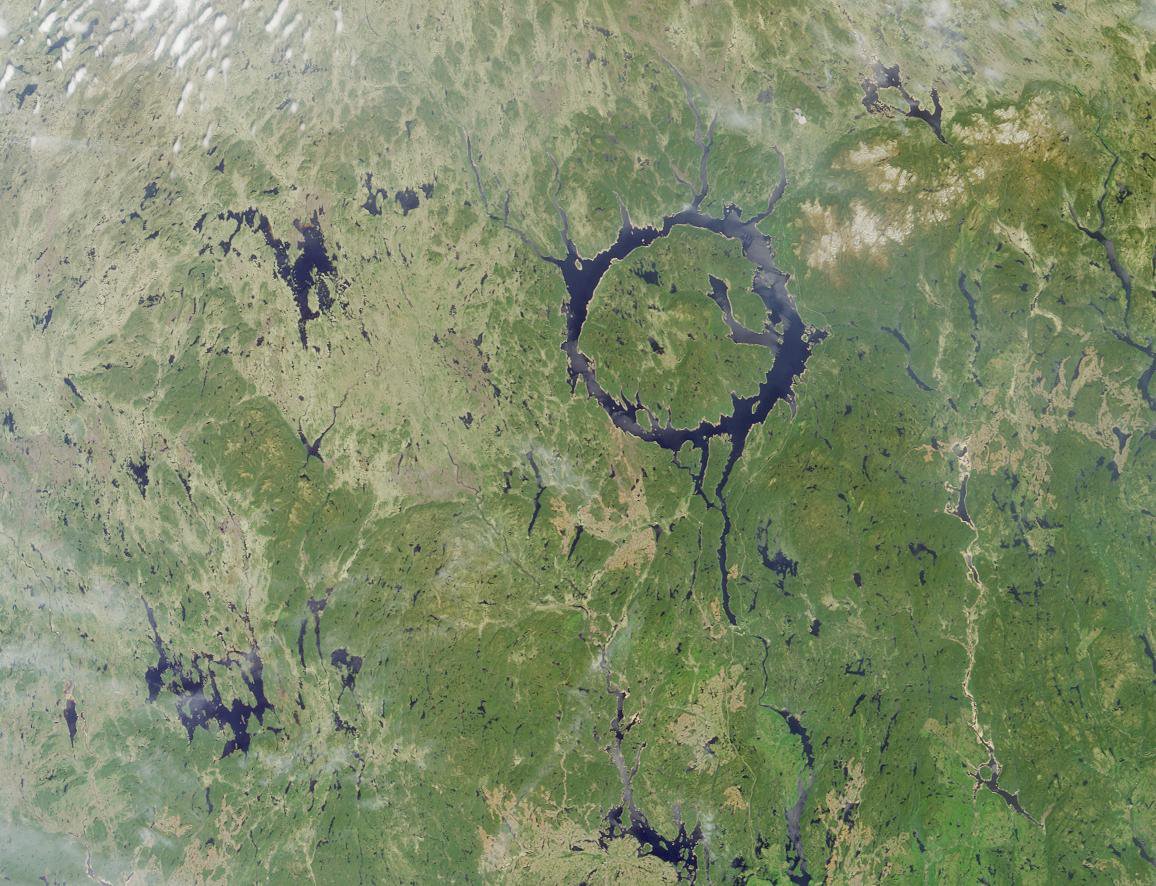

It was pouring rain the morning I drove in, and the last 200 km of the drive was on a winding logging road. Trucks laden with fresh-sawn trees zoomed past my tiny hatchback, but the perilous journey was worth it. Because here, deep in the wilderness, I got to tour one of the largest dams in North America. The storm cleared up by the time I got to the top, where I was presented with two contrasting views. In one direction, the Manicouagan Reservoir fills the landscape, framed by the rolling hills that rise on either side of the glacial valley. Turn around, and the generating stations and transmission lines snake out through the valley below. Manic-5 (the French pronunciation carries over into English conversations: say ma-NEEK sank, not MAN-ic five) powers households across Quebec. It provides non-intermittent baseload power, a critical part of a decarbonized energy grid, with excess power feeding into the grid in the Northeastern USA.

I am not alone in this obsession with electrical infrastructure: Many people in Quebec, particularly the French-Canadian majority, have a surprisingly broad excitement and nerdery for the state-run utility, Hydro-Quebec, which operates Manic-5. My pilgrimage wasn’t something I had to pull strings to arrange – it was a free public tour, and indeed about 8,000 visitors drive up the logging road every summer to marvel at the dam and to honor the unique history of energy in Quebec. And so I joined them, traveling across the province to better understand the engineering, history, and climate impacts of Quebec’s grid.

PLANNING & STRATEGY.

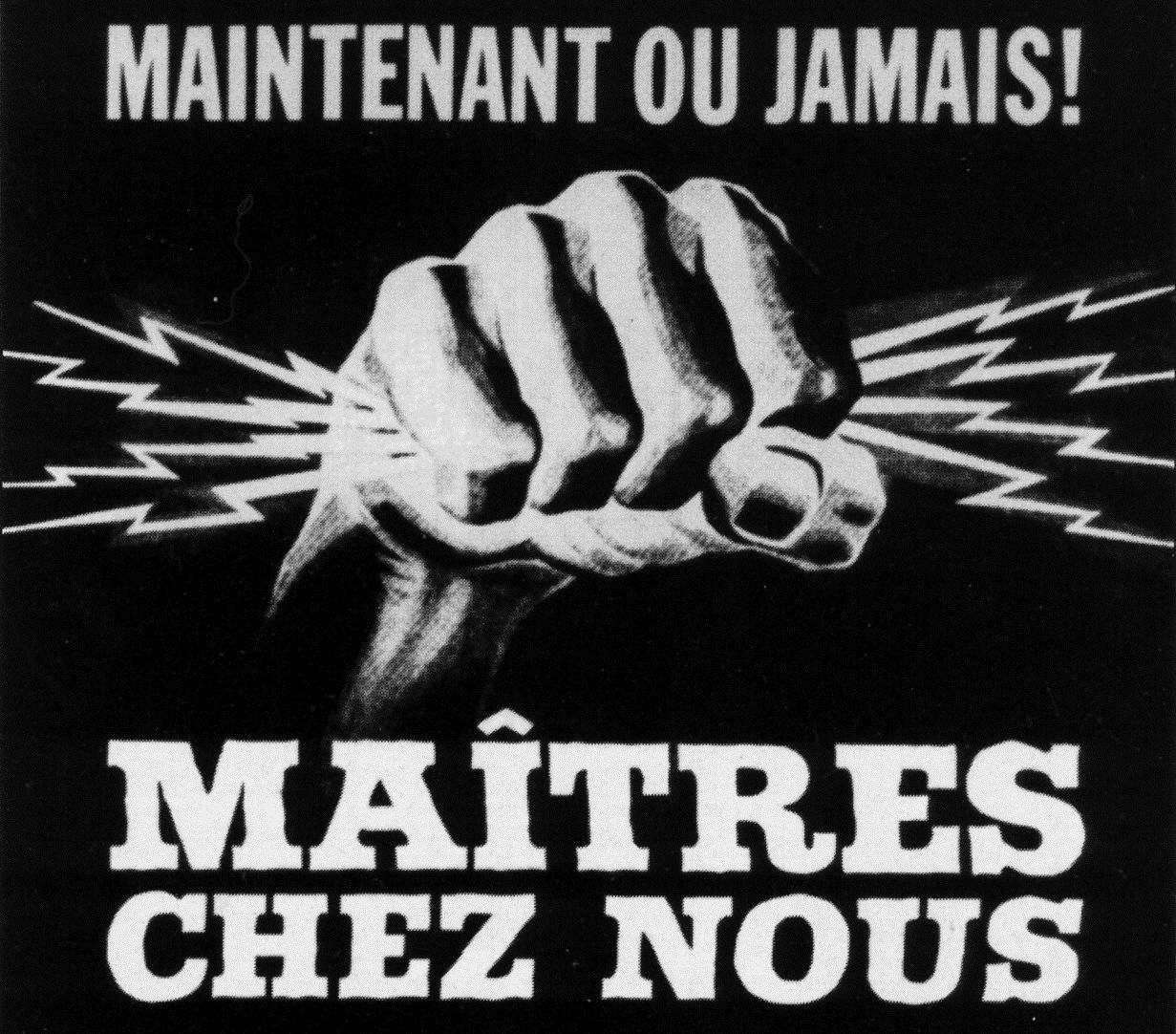

Public adoration for Hydro-Quebec was spurred on by its creation during the Quiet Revolution, a movement that reoriented Quebecois identity and politics back towards its francophone roots. The first Europeans in Quebec were French, arriving in the early 1600s, but after a military defeat in 1760, it became an English colony. For the next two centuries, the English minority controlled the majority of wealth, power, and industry in Quebec; francophones were marginalized as Canada modernized. But tides changed in the 1960s, when political leaders took great strides to protect the French language and increase economic opportunities for francophones. Affordable access to energy, particularly for low-income francophones, was seen as a key goal of the movement, and in 1963 Hydro-Quebec nationalized eleven private utilities and began decades of development. The newly integrated utility helped usher in a francophone professional class (today it employs over 20,000 people, who conduct their work almost exclusively in French) and delivered on the promise of affordability (Hydro-Quebec’s residential rates are considerably lower than neighboring regions: about half of rates in Ontario, and nearly five times lower than in New York).

MAKING & MANUFACTURING.

Deep in the boreal forest, the site surrounding Manic-5 is equipped with an educational center to host tours, and buses to ferry visitors to the top of the dam. While my abysmal French isn’t a huge hindrance in bilingual Montreal, here on tour I was the only visitor who wasn’t fluent. Like the rest of Hydro-Quebec’s operations, tours are provided primarily in French, so I had called ahead for accommodations. The gracious guides improvised English translations while my bilingual friends filled in the gaps. I was learning Hydro-Quebec’s history for the first time, but it was clear that the other tour attendees – who, save for my friends and I, were exclusively francophone Quebecois – were reconnecting with a familiar story. At one point our guide broke into song, and it quickly became evident that many of the other attendees knew the ballad well. I later learned it was La Manic by Georges Dor, which immortalizes the boredom and loneliness of the construction workers who built Manic-5:

Si tu savais comme on s'ennuie (if you only knew my ennui)

À la Manic (at Manic)

Tu m'écrirais bien plus souvent (you would write much more often)

I felt like a voyeur, peeking in on cultural nostalgia that was utterly obscure to me. George Dor is not a household name in English Canada, and I would venture that very few of the 159,124 views La Manic has racked up on YouTube originate outside Quebec. But for a generation of Quebecois, dam construction flooded the public consciousness as family members made the lonely trek to isolated work camps. There was even a live stream of construction broadcast at Montreal’s Expo 67 (impressive technology for the time!).

Manic-5's site preparation began a few years before Hydro-Quebec's 1963 nationalization, and by 1965, it was the largest construction site in North America, with 12,900 workers. First, workers built a temporary cofferdam to redirect the river into diversion tunnels blasted from the granite. A lumber mill and aggregate facility were built to alleviate the need for imported formwork and crushed rock. Cement for the dam couldn’t be produced locally, so shipments arrived every twelve minutes for four years, and cable cars, installed above the formwork, poured concrete around the clock.

Manic-5’s arch and buttress construction is quite efficient. The 13 arches distribute the load from the reservoir into 14 supporting buttresses that rest on the granite bedrock. While considerably longer than the Hoover Dam, Manic-5 contains roughly two-thirds of the concrete, at 2.5 million cubic meters.

MAINTENANCE, REPAIR & OPERATIONS.

Today there are two generating stations at Manic-5, with a total installed capacity of 2,660 MW; for reference, the Hoover Dam has an installed capacity of 2,080 MW. Beyond Manic-5, the size of Hydro-Quebec’s generating system is staggering. The most powerful facility is the Robert Bourassa generating station, at 5,616 MW. Overall the utility operates 28 large reservoirs, 61 hydroelectric generating stations, and 24 thermal plants for a total installed capacity of 37.2 GW. This means the generating capacity of this Canadian province (with a population around 8.5 million) is greater than the entire country of Malaysia (34.31 GW; population around 32 million) and a little under half the state of Texas (85 GW; population around 28 million).

But the mega-dams and generating stations that litter northern Quebec reshaped a landscape that was already occupied when Quebec’s politicians set their sights on developing it. The reservoirs behind Manic-5 and other dams flooded unceded Indigenous territory, and in general Hydro-Quebec’s 20th-century expansion was carried out without consulting the surrounding Indigenous nations. This had enormous impacts: the Manicougan Reservoir forever changed the ecosystem that supported the Pessamit Innu. And while these isolated dams serve electricity to the cities, many remote Indigenous communities still rely on diesel for electricity generation. Electrifying the landscape of Northern Quebec enabled prosperity for French Canadian settlers, and independence from the English elite. But it came at the expense of the land’s original inhabitants. As geographer Caroline Desbiens put it, “in this era of decolonization and affirmation of French Canadian identity, the irony of uttering the word “Masters in our own home” on Innu ground was not apparent.”

The Innu eventually negotiated a payout of a paltry $150,000 ($116 per person) for that complex of dams, and are in ongoing litigation over damages from another project. The Cree and Inuit managed to negotiate a more comprehensive treaty in the 1970s, following lengthy court proceedings.

This dispossession and displacement have shaped a pretty dismal legacy, and I hope the coming rush to rebuild energy systems will be imbued with more equality and justice. And to their credit, Hydro-Quebec has changed tactics since the 1960s. The utility canceled a hydro project on the Great Whale River in 1994, following years of concerted effort by the Cree nation. Recent dams on the Romaine River underwent consultation with Indigenous groups, and construction was subject to agreements with the Innu. The Canadian portion of the Champlain Hudson Power Express transmission line will be co-owned by Hydro-Quebec and the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke.

DISTRIBUTION & LOGISTICS.

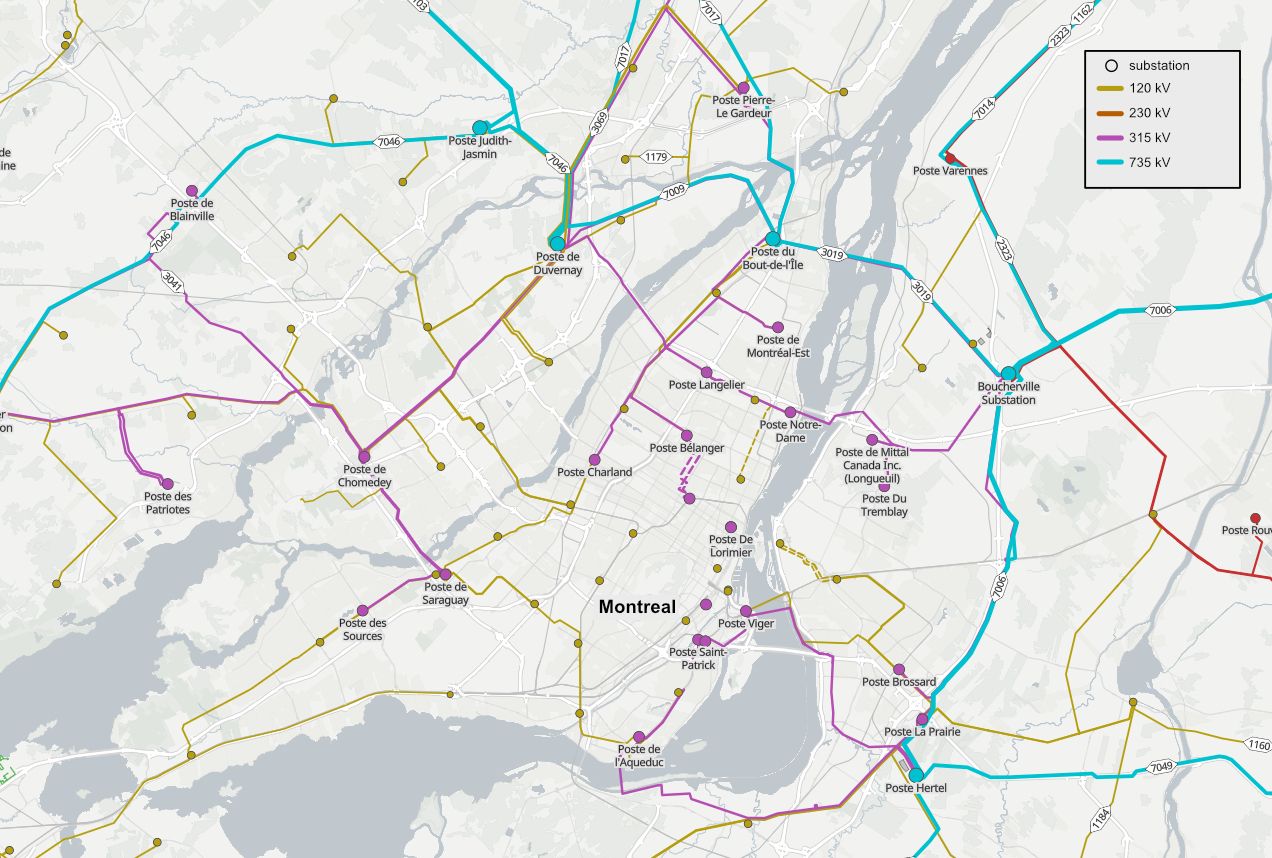

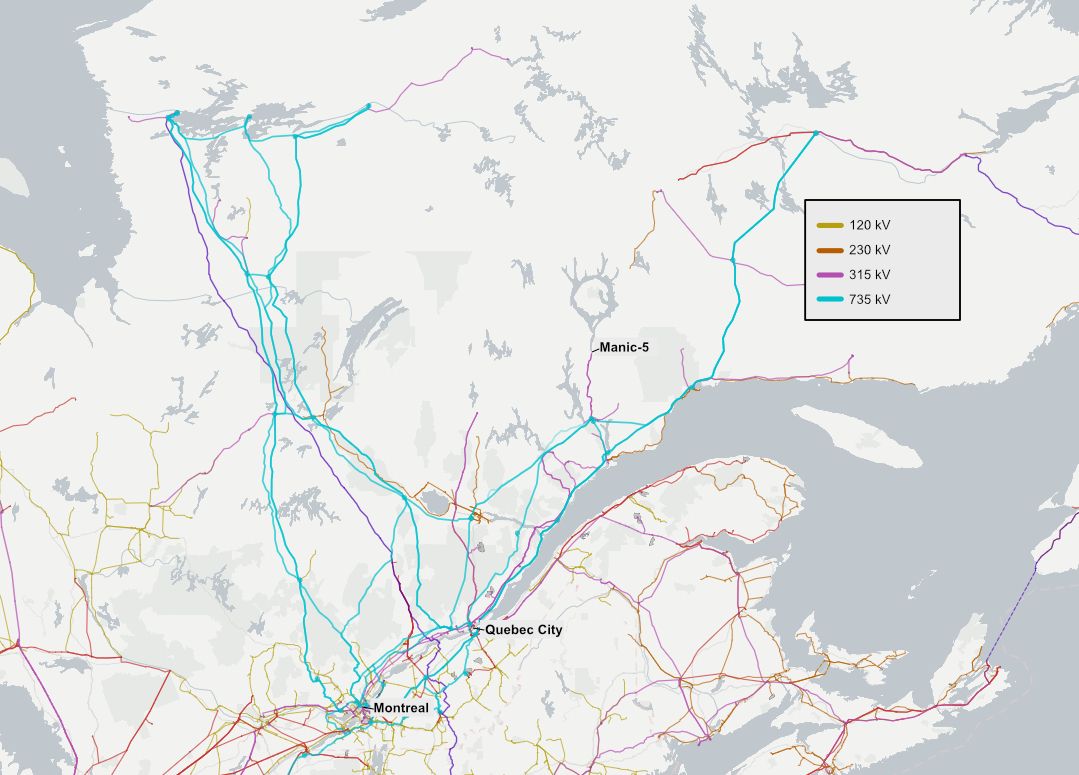

Developing hydroelectricity was an opportunity afforded by strong political tides, but it was only possible because of Quebec’s huge land base and myriad rivers. Quebec’s population is concentrated around Montreal and Quebec City, both of which lie near its southern border, but the province stretches nearly 2000 kilometers to the north and has a landmass that’s a little over 1.5 million square kilometers – more than double the size of Texas. Because much of that land was sparsely populated, Hydro-Quebec designed a system that harnesses power from far-off rivers – then transmits it hundreds or thousands of kilometers south to benefit urban populations.

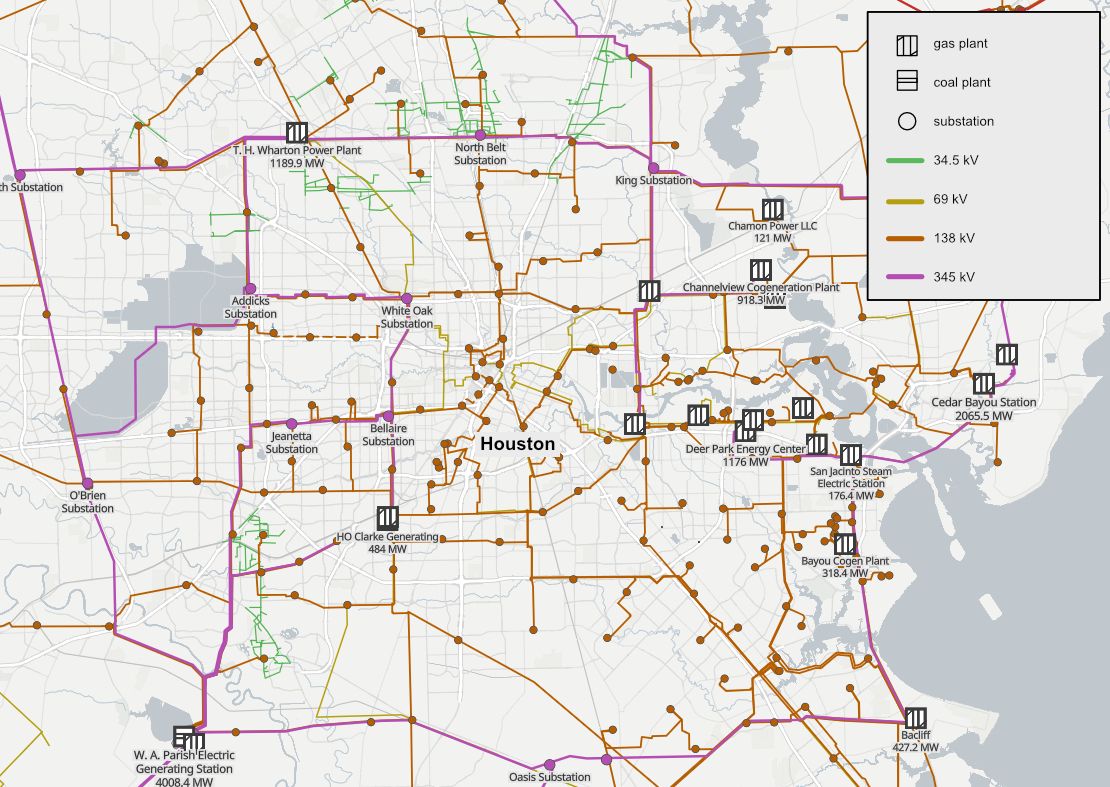

This stands in contrast to the dominant generation strategy elsewhere in North America, where fossil fuel-burning plants are typically built close to major population centers. Take, for instance, the grid around Houston, Texas: There are 18 power plants within city limits, primarily burning gas.

In contrast, there are no thermal generation plants near Montreal, nor any electricity generation within the city at all. Instead, electricity from hydroelectric generating stations hundreds of kilometers away is transmitted to the city through very-high voltage lines.

INSPECTION, TESTING & ANALYSIS.

Manic-5 impounds the massive Manicougan reservoir, which fills a meteorite impact site with 140 billion cubic meters of water – the volume of about 47 million Olympic swimming pools. While construction of the dam wrapped up in 1968, it took a full 13 years for the reservoir to fill. Like all reservoirs, it emits greenhouse gases – predominantly methane from decomposing biomass. While emissions from hydroelectricity are more variable than any other energy source (see page 29 of this pdf), the age and latitude of the reservoir in question are the most significant factors. Quebec’s decades-old, northern reservoirs are in the category with the lowest emissions; studies have found that methane levels return to the same range as nearby lakes within four years. A recent independent analysis of emissions from Quebec’s reservoirs found that CO2 equivalent emissions were higher than anticipated (34.5 g CO2eq/kWh) but are still an order of magnitude lower than burning gas, which emits 433 g CO2/kWh.

SCOPE CREEP.

It’s hard to express just how important Hydro-Quebec is to Quebecois identity. This isn’t academic speculation: the connection between electricity and the Quiet Revolution is taught in Quebec’s primary schools. Many dams are named after politicians from the Quiet Revolution era – Manic-5 is officially dubbed the Daniel Johnson dam, for a provincial premier.

It’s something of an accident of history that Quebec ended up with a decarbonized electricity system decades before carbon emissions were a political concern. Quebec's approach is a lesson in how inextricable infrastructure is from culture: without linguistic tensions and the Quiet Revolution, modern-day Hydro-Quebec might not have been built. It’s not necessarily a model to replicate around the world; for one thing, Quebec’s available hydrology is unique, and the way the system was built defined who would be beneficiaries and who would not. But it’s a robust, fossil fuel-free system that millions depend on, both in Quebec and in neighboring states and provinces that import from Hydro-Quebec.

Hydro-Quebec bills itself as “the battery of the Northeast,” and I think the title is appropriate. The utility exports dozens of terawatts of hydroelectricity to other markets, balancing the flow of intermittent renewables. Next week, I’ll touch on some of the big transmission projects underway in the region.

Thanks to Lee, Thomas, and Fiona for their company and conversations on hydro road trips. Thanks also to Daemon, Dave, and Kyle for joining in on shorter journeys and to Deb and Stewart for providing expert feedback on drafts. If you find yourself in Quebec, I really recommend checking out a Hydro-Quebec facility tour (many are closer to Montreal and Quebec City than Manic-5).

Love, Hillary

p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here’s what we’re doing about it.

You can read part 2 here.