Dealing with a crisis can be exhilarating. The Bay Area was recently inundated with three weeks of torrential rain — the kind of winter deluge that feels like a remnant of a previous, less drought-stricken California. It came as a surprise, and many of us were not prepared. I (Kelly) recently moved into a new (well, very old) house, and soon discovered that some of the downspouts and grading couldn’t deal with that much water. My partner and I found ourselves making frenzied rain-splattered runs to the hardware store for downspout extenders and splash blocks, then rushing home to put them into temporary service to manage the unceasing flow of water. And we were not alone: Around the state, communities came together to fill sandbags and clear storm drains, troubleshooting their way through hundreds of acute, hyperlocal crises.

As Rebecca Solnit famously described in A Paradise Built in Hell, people tend to rise to the challenge in times of disaster, and even do it with joy and aplomb. It’s perversely fun to stand in the pouring rain, walling up sandbags and rigging up tarps. But there are limitations to what you can do in the moment. Disaster responses and mutual aid can fill some of the gaps left by failing infrastructure or underinvestment, but they can’t do everything. Now that the rain has stopped — or at least paused — there’s an opportunity to retain that sense of urgency, and figure out how to improve the systems we’re working with so they can better cope with the next crisis. For me this means working on a permanent downspout and drainage fix. For California communities, it should include devising robust plans for local climate mitigation and adaptation, and increasing funding to repair and remediate infrastructure in neglected neighborhoods so people aren’t left soaked and stranded when the next storm comes.

The most clicked link from last week's issue (~5% of opens) was a new flight sim controller, the Yawman Arrow. In the Members' Slack, highly specific questions get thorough responses. From help finding the right nomenclature that's at the tip of your tongue, to dialing in feeds and speed, the community's got you covered.

JOBS.

- Nikon is hiring a mechanical engineer in Manassas, VA.

- Glowforge is hiring an embedded hardware engineer in Seattle.

- Heirloom is hiring a senior laboratory technician in Brisbane, CA.

- Terraline is hiring a director of battery engineering in Fremont, CA.

- The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation is hiring a preservation manager in Spring Green, WI.

- More jobs on Scope of Work's job board; you can promote the role you're hiring for here.

SPONSORED.

- New year, new projects! And if you're in NYC, your place for projects is the New York Industrial Collective. With 24/7 access, our facilities can help you tackle the most ambitious extracurricular stuff – from electronics, to prototyping, to crafts and woodwork. Don’t spend years buying your own Festool, Sawstop, Formlabs, and Tektronix equipment – use ours instead ;)

PLANNING & STRATEGY.

Perhaps it’s the legacy of wood fire heating, but people expend a lot of energy heating and cooling the buildings and rooms we inhabit – instead of heating or cooling things (bodies, equipment, sensitive electronics) directly. Heating and cooling buildings is incredibly energy intensive, accounting for 13% of all energy consumed in the US in 2016. Localized thermal management (LTM) — that is, heating the area directly around a person or object rather than a whole room or space — can be a much more efficient alternative. One study showed that reducing the temperature in an office building from 20.5° to 18.8° C – and giving people a heated chair – saved 35% on energy costs while increasing people’s reported comfort levels.

While LTM systems often skew high-tech (think thermal fabrics and personal heating and cooling robots), one has existed in its current form for a hundred and twenty years: the hot water bottle. This article from Low Tech Magazine traces the hot water bottle’s history and proposes how they can be integrated into daily life, with the potential for significant energy savings: You can heat 900 hot water bottles for the cost of heating a modestly-sized home for one day.

We’re most familiar with electric fences as a tool to limit the movement of animals across a terrestrial landscape, but electrical pulses have also been deployed underwater to manage the movement of Asian carp. Asian carp – an umbrella term for four species that were introduced to the southern United States in the 1960s – have become highly invasive. They have thrived in US rivers to the extent they now comprise up to 95% of the biomass in some waterways; they have no natural predators, can grow up to 40 kg, and consume up to 5-15% of their body weight every day. But carp haven’t spread to the great lakes yet, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has taken great measures to prevent them from moving from the Mississippi River Basin into Lake Michigan – including deploying two barriers to send direct pulses of electricity across the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. This video has a great overview of the complexities of electrifying a canal, and what it means for the boats crossing through it and other wildlife in the area.

MAKING & MANUFACTURING.

Exploded view drawings and diagrams show the components (and often order of assembly) of an object. Each component is separated out “as if there had been a small controlled explosion emanating from the middle of the object” (thank you for that poetic description, unnamed Wikipedia author). Leonardo da Vinci drew an exploded view gear assembly in the 15th century, and countless assembly manuals, landscape designers, and Microsoft PowerPoint users rely on them to this day. But what if you want to make a physical exploded view with components of actual products? It’s fairly straightforward if you’re arranging parts on a flat surface, but things get trickier if you want to show them hanging in 3D space. Steve Giralt’s internet-famous 2016 video of burger components seemingly levitating before being dropped into the perfect burger shows that trying to achieve an exploded view in “real life” is a complex production. As this behind-the-scenes video shows, the shot used a high-speed robot camera arm, rigging equipment, and fishing wire to film a couple of seconds of video which were significantly slowed down and composited for the final video.

MAINTENANCE, REPAIR & DECONSTRUCTION.

While diligently reading the emergency landing instructions found in every airplane seatback pocket, we sometimes fantasize about what it would be like to throw open the exit door and deploy the bouncy yellow escape slide. Outside an actual emergency landing, though, it’s unlikely we’ll ever get to give it a try. For disaster relief and emergency response professionals, there is a place to practice for these unlikely occasions: disaster preparedness training facilities. FEMA runs The Center for Domestic Preparedness, where visitors can experience a simulated Sarin gas attack, triage injuries in a simulated train derailment, or decontaminate a simulated chemical spill. Private sector company Guardian Centers also runs a disaster preparedness facility on their massive Georgia campus. Attractions at this veritable disaster theme park include a 1.7 km four lane highway for simulating accidents and terror attacks, and two city blocks of “dynamic collapsed structures” for practicing search and rescue.

Most buildings slated for removal are demolished, and the rubble carted off to landfill. It’s a method that’s fast but wasteful, especially as an estimated 40% of global material flows can be attributed to construction, maintenance, and renovation of structures. As an alternative, we’re interested in building deconstruction — why not think of an existing building as a repository of valuable materials that could be made available for future reuse? In the US, some jurisdictions have put in regulations for the deconstruction of homes to prevent usable materials from being landfilled. In other places large-scale deconstruction is already happening in order to repurpose materials — including multi-story office blocks in Japan and the Netherlands that were deconstructed floor-by-floor.

The Bow Gamelan Ensemble devised a way to “play” the industrial history of London’s waterways — the crumbling buildings, scrap metal, and unused structures left behind when the shipping industry transformed and heavy manufacturing moved further from the center of the city. With instruments made from rusted metal and other rubbish, the group of three artists explored the potential to salvage art from abandoned infrastructure. The group’s 1980s performances captured (or at least referenced) something of the drama and danger of the now-evacuated industrial past — perhaps a strange and scrappy precursor to the stagier and more palatable postindustrial beatmaking of Stomp!, the incredibly popular percussion group.

DISTRIBUTION & LOGISTICS.

The majority of the world’s internet traffic travels between countries through more than 500 sub-sea cables. Most years there are more than a hundred instances of subsea cable damage, but in most cases data can be rerouted as repairs are made. In Egypt, 16 cables carrying about 17% of the world’s traffic all come on land together for a 100 km stretch to connect Europe and Asia. Experts have warned that this chokepoint has significant risk, making this overland route in Egypt “arguably, the internet’s most vulnerable place on Earth.” The 2021 grounding of the Ever Given in the Suez Canal was a very real demonstration of how chokepoints can cause a single point of failure for the world’s interconnected logistics systems.

How to while away the hours searching shipping manifests to track where the things you own come from.

INSPECTION, TESTING & ANALYSIS.

In the wake of the infamous Mary Mallon (Typhoid Mary) and a broader rise in concerns about food safety, trailblazing health commissioner Dr. Sigismund Goldwater ushered in the first health department inspections of New York City’s restaurants in 1916, as outlined in this wide-ranging story. However, when inspections began, restaurateurs had to be assured that the quality of their cooking was not in question: “The department wishes to emphasize that its inspections and resulting grading have nothing to do with good or bad cooking.”

Some new (and much hyped) research on Roman concrete, and its ability to “heal” cracks up to .5 mm wide. Though the original Roman concrete recipes were famously lost for centuries, much recent effort has gone into recreating and understanding them. This new paper makes the most direct hypothesis to date, suggesting that by using quicklime (solid calcium oxide) rather than slaked lime (lime premixed with water, which forms calcium hydroxide), some Roman builders were able to create exothermic reactions in their concrete slurries, resulting in unique chemical compounds and faster cure times. And as the cured concrete aged and eventually deteriorated, lime-rich regions (“clasts”) would get wet and recrystallize as calcium carbonate, “healing” any nearby cracks.

But as Brian Potter points out (and as Spencer wrote in this newsletter in 2021) much of the decay in modern concrete structures results from corroded steel rebar – a technology that wasn’t present in Roman concrete, and which allows modern concrete to be used in ways that the Romans could have never imagined. There are already options for slowing or preventing this kind of decay, including using stainless steel, fiberglass, or aluminum bronze rebar. But these solutions come at high cost, and ultimately it’s unclear if modern society wants its buildings to last longer than fifty or a hundred years. In the end, Potter seems skeptical whether this research will have any practical applications, and we wonder whether a careful reading of Stewart Brand’s work might have a larger impact.

SCOPE CREEP.

The long, sordid, and ingenious history of birds transporting drugs in cute little backpacks.

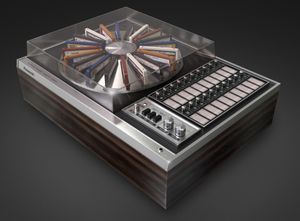

Some Chuck E Cheese franchises still use floppy disks to program their animatronics shows. Somehow we were both shocked and utterly unsurprised to discover this.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members for supporting Scope of Work. Thanks also to Mich for getting us hooked on hot water bottles again.

Love, Anna, Kelly

p.s. - We made this neighborhood bingo card as part of a project we do each year, which you can take on your next walk around town.

p.p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here’s what we’re doing about it.